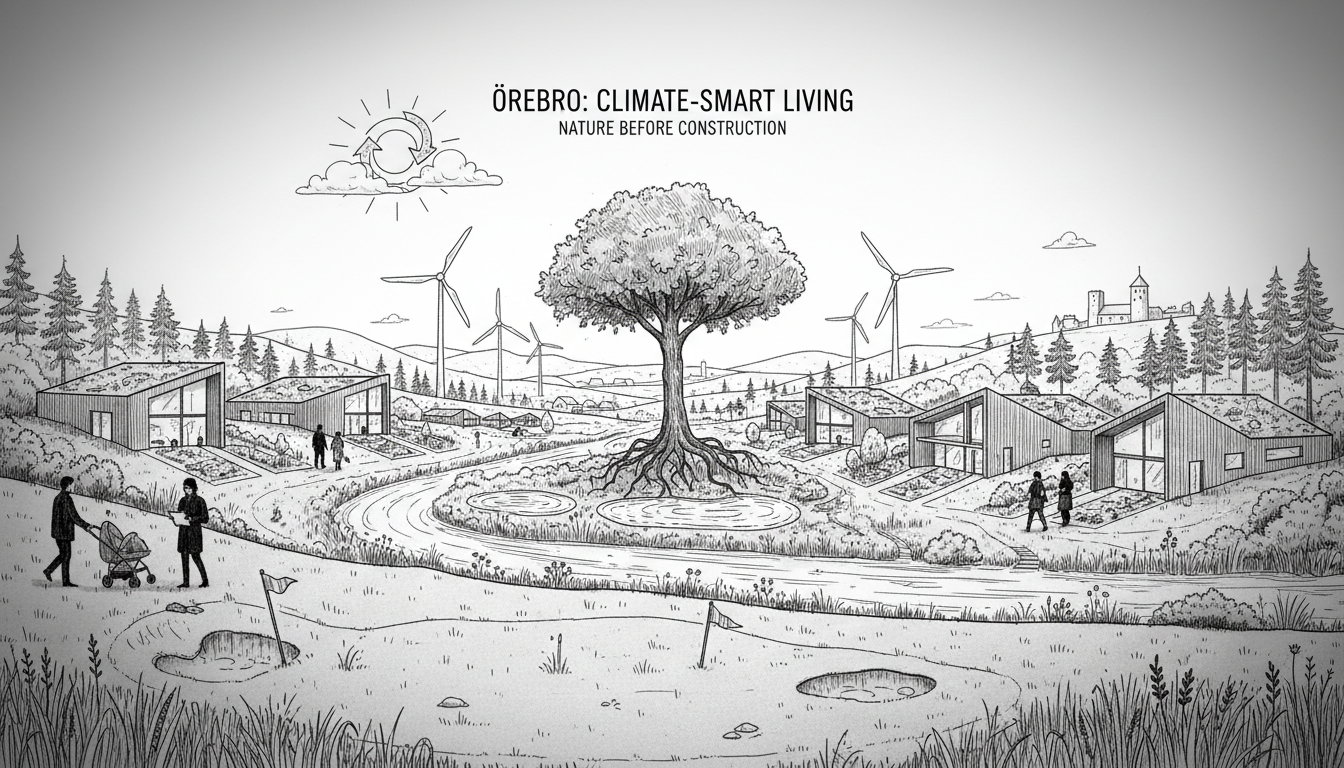

An abandoned golf course and former agricultural land in Örebro, Sweden is undergoing a remarkable transformation into a nature-first residential community. The Heden district represents a pioneering approach to urban development where natural landscapes are created before construction begins.

City architect Peder Hallkvist explains the unconventional strategy. "We haven't really worked this way before, but I think we will need to think much more like this in the future," he stated.

The streets already feature lampposts, bicycle stands, small playgrounds and waste containers. Garden beds remain partially covered to prevent weed growth, indicating the ongoing development. Remarkably, no plots have been sold yet, but Örebro municipality chose to complete the surrounding environment first.

Across a small road, wetlands stretch across the landscape. An electric fence protects water areas to give birds peace, while gravel paths wind through the space. The area includes a barbecue spot by the water and raspberry bushes spreading across a small hill.

"From having just a handful of bird species in the area, we now have over 100, including some endangered species," Hallkvist noted. "There's also other wildlife present - beavers and many butterflies."

The transformation from abandoned golf course to thriving ecosystem demonstrates Sweden's growing commitment to climate-adaptive urban planning. The wetlands serve multiple purposes, handling water from Älvtomtabäcken creek that flows toward Svartån river through central Örebro.

These wetland reservoirs can naturally flood and retain water. The detention pond collecting street runoff from the new neighborhood integrates as a natural environmental feature rather than buried technical infrastructure common elsewhere.

"This entire landscape reduces flood risks downstream, meaning in other city districts too," the city architect emphasized.

The natural environment also functions as a carbon sink, capturing and storing carbon dioxide. This approach addresses climate adaptation, biodiversity preservation, and flood risk management simultaneously.

"The bonus is the tremendous quality of life benefits for future residents of the new homes," Hallkvist added.

Four new districts totaling approximately 1,400 homes will eventually surround the wetland area in a cloverleaf pattern, with Heden being the first. Interested builders must engage in dialogue with the municipality, which expects construction to reflect inspiration from the natural landscape.

Professor Mikael Granberg, who researches societal risks at Karlstad University, provides context about broader municipal practices. He notes that municipalities have recently built housing in flood-risk areas despite climate concerns.

"From a climate risk perspective, this seems completely insane," Granberg observed. "But municipalities must consider other factors."

Waterfront properties remain attractive for attracting new residents and investments. Urban densification popularity can also mean water has nowhere to go when heavy rains come.

"Climate risks often become subordinate to growth goals," Granberg explained. "This can lead to building cities that actually produce risks."

The Örebro project aligns with the "sponge city" concept pioneered by Chinese researcher Kongjian Yu in 2013. This approach enables cities to manage excess water from downpours or flooding internally rather than simply diverting it elsewhere.

Approximately 1.8 billion people worldwide face flood risks, making nature-based solutions increasingly critical for urban resilience. The Swedish project demonstrates how green spaces, parks, and trees can transform urban water management while creating attractive living environments.

This development represents a significant shift in Scandinavian urban planning philosophy, prioritizing long-term environmental sustainability over short-term construction efficiency. The approach could influence future projects across the Nordic region as municipalities confront increasing climate challenges.