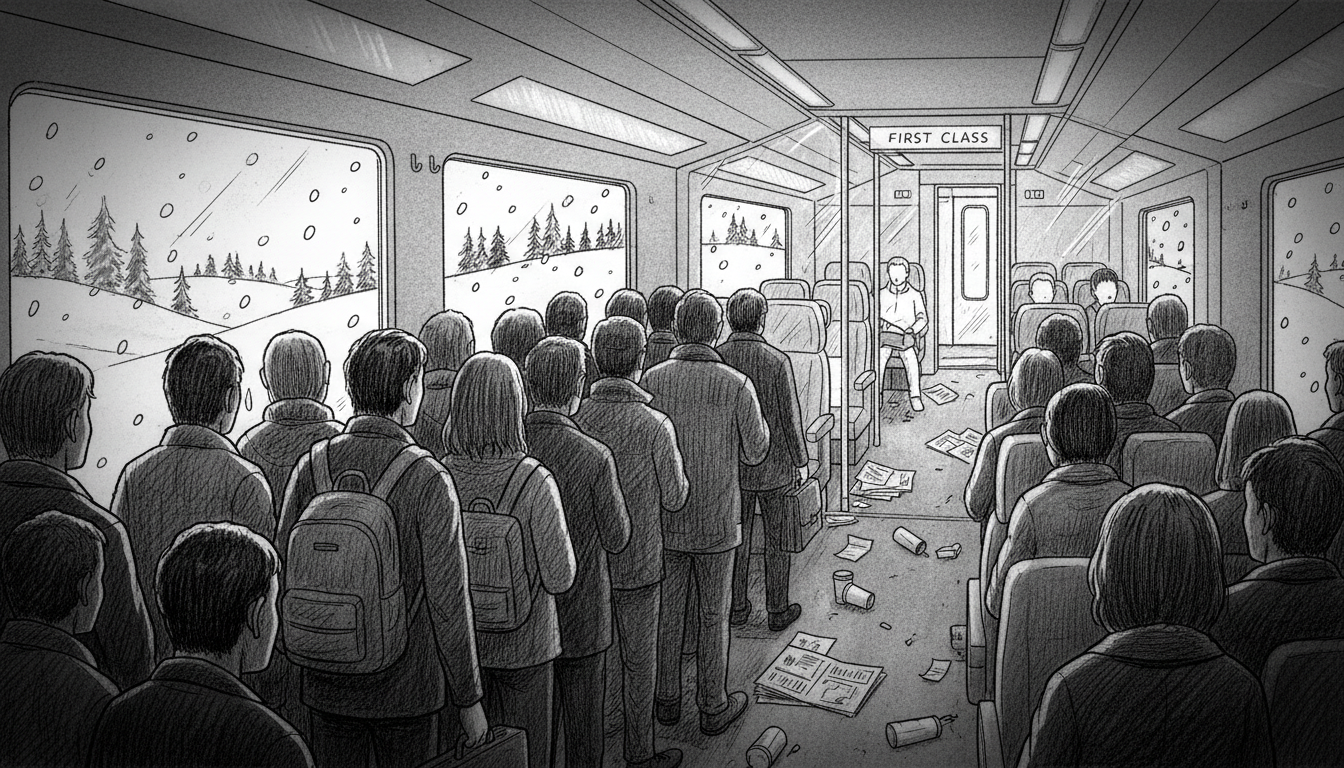

Danish rail passengers face crowded conditions while premium carriages remain empty, highlighting a growing frustration with the country's train system. The situation reveals fundamental tensions between commercial service offerings and passenger rights.

Imagine booking a train ticket with a reserved seat. You arrive at the platform only to discover your carriage has been removed from the train. This exact scenario played out recently when a journalist traveling from Odense to Copenhagen found herself standing in crowded aisles for over an hour. Meanwhile, first-class compartments sat completely empty just feet away.

The problem stems from DSB's strict separation between standard and premium services. First-class sections, known as DSB 1', remain off-limits to standard ticket holders even when carriages go missing and seats sit vacant. Company officials defend this policy by emphasizing that premium services must maintain exclusivity for those who pay extra.

Tony Bispeskov, DSB's information chief, acknowledged passenger frustrations but stood firm on the policy. He explained that first-class represents a luxury product that passengers purchase separately. Opening these sections during service disruptions would undermine their value proposition.

Current regulations from the Danish Transport Authority complicate matters further. Rules permit extremely crowded conditions where passengers stand pressed together in aisles. The guidelines essentially allow standing room only scenarios even when passengers have paid for guaranteed seating.

This situation raises questions about consumer protection in Danish public transport. Passengers who purchase reserved seats receive only minimal compensation when their carriage disappears. They can claim a 30-krone refund through DSB's website, but this hardly compensates for standing during long journeys.

The incident reflects broader challenges in Nordic transport systems balancing commercial offerings with public service obligations. Similar debates have emerged in Sweden and Norway where railway companies face criticism for prioritizing premium services during operational disruptions.

For international readers and expats in Denmark, this highlights important considerations when using Danish rail services. The system operates differently from many other European networks where first-class seating often opens to all passengers during overcrowding.

The solution for affected passengers remains limited. They can approach train staff who might direct them to any available seats elsewhere in the train. Otherwise, they must stand while watching empty premium seats pass by their journey.

This situation demonstrates how commercial considerations sometimes conflict with practical passenger needs during service disruptions. The empty first-class carriages symbolize a wider discussion about resource allocation and customer service priorities in public transport.