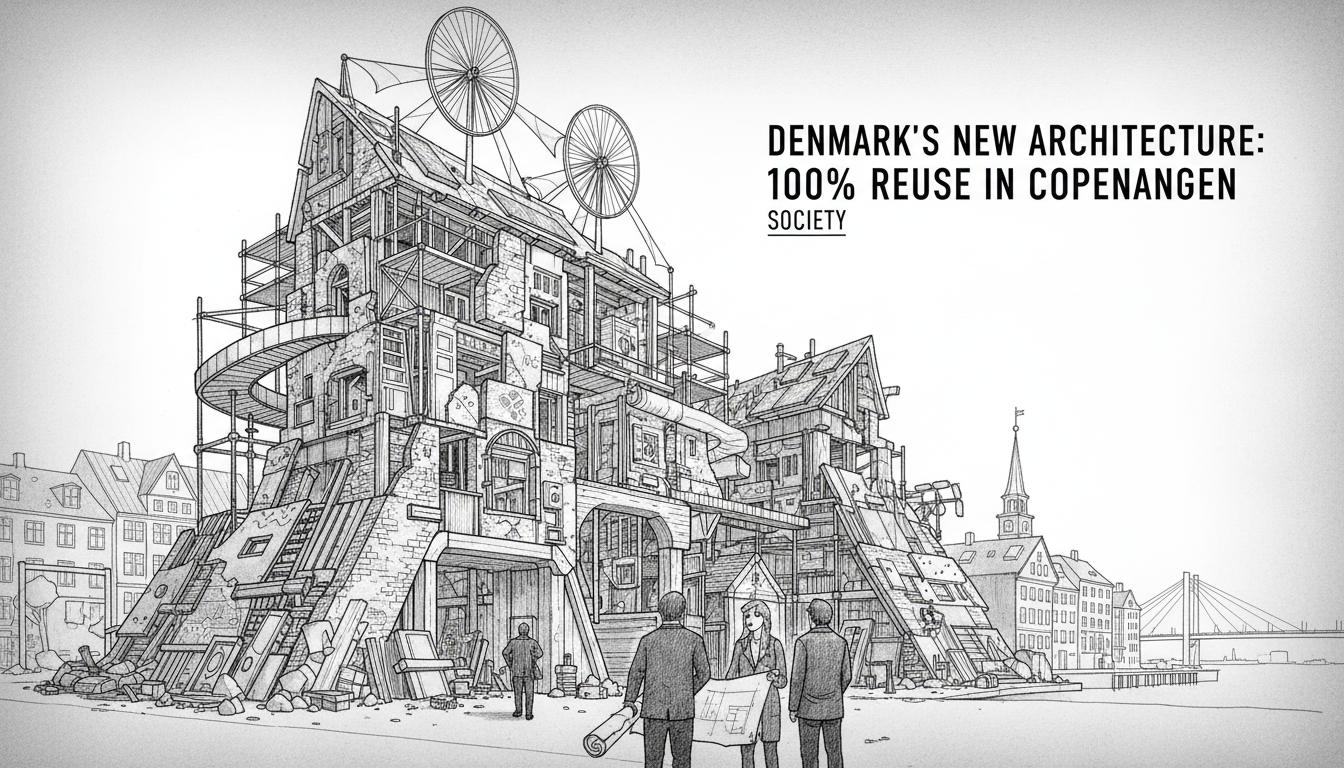

Copenhagen sustainable architecture is undergoing a radical transformation led by a new generation of designers. On a busy street in Nørrebro, a former furrier and office building now pulses with life as an ‘activity hub’. This project embodies a fundamental shift in Danish building philosophy where nothing is new and everything is reused. The movement prioritizes adaptive reuse over demolition, challenging decades of construction norms to meet urgent climate targets. For architects like those behind this transformation, the future of building is circular, creative, and already standing all around us.

From Furrier to Community Hub

The Nørrebro building’s metamorphosis is a masterclass in creative preservation. Its outdated 20th-century shell now houses a café, gallery, dance studio, workshops, and offices. Original structural elements, from beams to brickwork, were meticulously retained and integrated into the new design. This approach preserved the neighborhood's architectural character while injecting modern functionality. The project demonstrates that sustainable design can foster vibrant, gade-snedige (street-smart) community spaces. It proves environmental responsibility and urban vitality are not mutually exclusive goals.

Local residents initially watched the renovation with curiosity, unsure of the building's future. Today, it serves as a social anchor, hosting events that reflect Nørrebro’s diverse cultural fabric. “We didn't just save a building; we reactivated a piece of the city's memory for new generations,” said a project architect involved in the redesign. This focus on social value alongside material reuse is a hallmark of Denmark's contemporary approach. It aligns with broader Danish social policy goals of creating inclusive, integrated urban environments where community centers play a vital role.

The Carbon Cost of Construction

The drive for adaptive reuse is fueled by stark environmental data. The global building sector accounts for roughly 40% of all carbon emissions, according to the UN Environment Programme. In the European Union, demolition and construction activities generate over 35% of total waste. Denmark’s national commitment—a 70% reduction in greenhouse gases by 2030 and climate neutrality by 2050—makes tackling this sector imperative. New construction, even with energy-efficient operations, carries a massive ‘embodied carbon’ cost from manufacturing and transporting new materials.

“Every time we demolish a sound structure, we are throwing away a huge carbon investment and creating a waste problem,” explained a sustainability expert at a leading Danish architectural firm. “The greenest building is often the one that already exists.” This principle is pushing Danish municipalities to revise local planning guidelines. They are increasingly incentivizing renovation and imposing stricter requirements for demolition permits. The logic is clear: reusing a building’s skeleton can slash a project's carbon footprint by 50% or more compared to building new.

Circular Economy in Practice

Danish architecture firms are now embedding circular economy principles into their core practices. This goes beyond reusing entire structures to specifying recycled steel, upcycled brick, and reclaimed timber for interior fit-outs. The goal is to design buildings as material banks for the future. This shift requires new collaborations with demolition companies, material brokers, and craftsmen skilled in refurbishment. It represents a significant departure from the linear ‘take-make-dispose’ model that has dominated construction for generations.

In Copenhagen, this philosophy is visible in projects ranging from old industrial warehouses converted into apartments to schools expanded using modular components designed for disassembly. The city’s ambitious development plans, particularly in the Nordhavn and Ørestad districts, now explicitly encourage circular construction methods. This policy direction supports Denmark’s reputation as a leader in green urban development. It also creates a new niche for Danish design expertise, which is increasingly exported as a model for sustainable urban living.

Policy, People, and the Future City

The success of adaptive reuse depends on more than architectural will. It requires supportive national and municipal policies, flexible building codes, and a shift in public and developer perception. Denmark’s strict building regulations, often focused on energy performance in use, are gradually incorporating assessments of a building’s full life-cycle carbon impact. This holistic view makes renovation and reuse more financially and legally competitive against the allure of a blank slate.

There are challenges. Retrofitting older buildings to modern energy standards can be technically complex. The economic model, while often cheaper in materials, can require more labor and ingenuity. Yet the benefits extend beyond carbon accounting. Preserving existing buildings maintains the scale and texture of neighborhoods, supporting social cohesion—a key priority in Danish integration and social policy. It avoids the community disruption caused by demolition and years of new construction.

As one city planner in Copenhagen noted, “Sustainable cities are not just about technology. They are about stewardship, community, and making the most of what we have.” The unassuming building in Nørrebro stands as a physical manifesto for this idea. It asks a provocative question of every city planner, developer, and citizen: Before we dream of building new, what value can we unlock from what is already here? The answer will define the skyline and the sustainability of Denmark for decades to come.