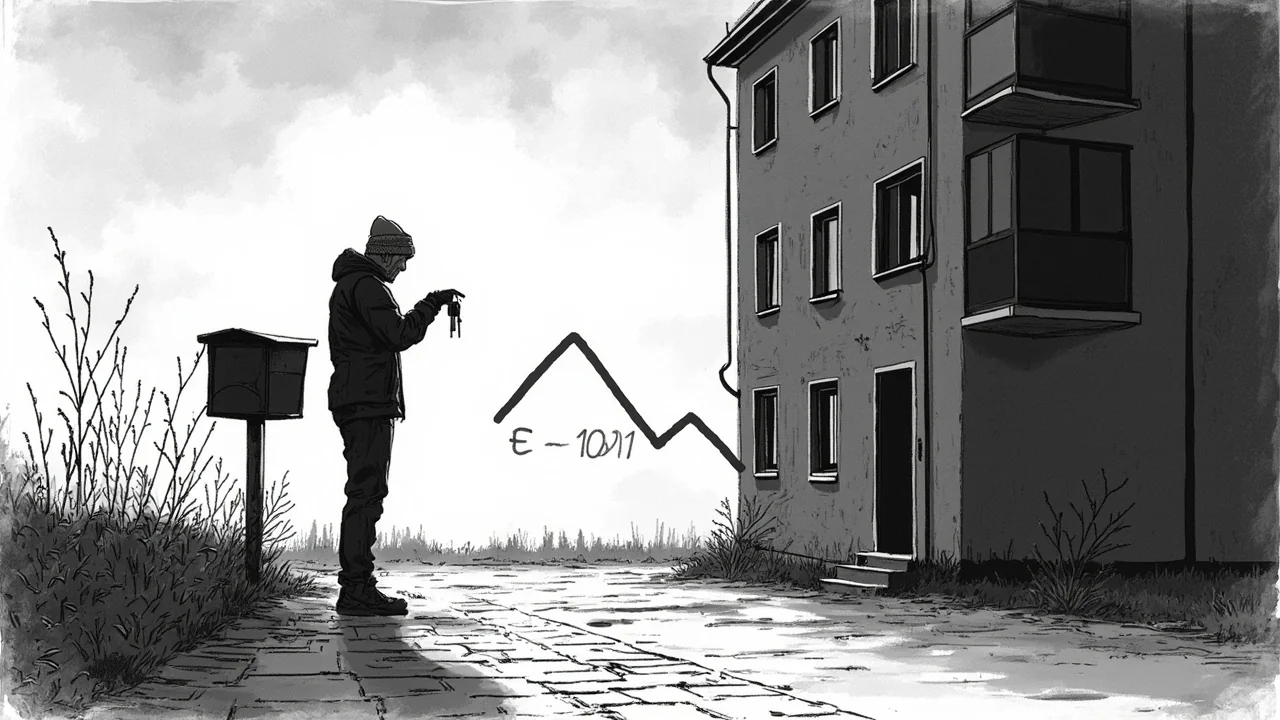

Helsinki's rental market presents a stark paradox for tenants like Ida Roitto, who terminated her Kallio district apartment only to see it immediately re-listed for over one hundred euros less per month. Her experience highlights a growing tension between existing tenancy agreements and rapidly shifting market prices in the Finnish capital. Roitto had lived in the two-room apartment for two and a half years, during which her rent was increased twice. The final increase came last autumn, just months before she decided to end her contract. Upon seeing her former home advertised at a significantly lower rate, she was left questioning the logic of the previous hikes during a period when overall market rents were beginning to soften.

A Personal Decision in a Shifting Market

Ida Roitto's choice to terminate her lease was a personal calculation, but it was immediately followed by a confusing discovery. While browsing listings from Sato, one of Finland's largest rental housing providers, she found her old apartment available for a monthly rent more than one hundred euros cheaper than what she had been paying. This price differential occurred despite a general trend in 2023 where new rental contracts in the Helsinki region showed signs of stabilization or even slight decline after years of steady increase. For existing tenants, however, annual adjustments often continued upward based on older index clauses or operational cost calculations, creating a disconnect.

The Provider's Policy on Existing Contracts

The core of the issue lies in the standard practices of housing companies. In response to inquiries, Sato stated they do not typically lower the rents of existing, valid rental agreements. This policy means that sitting tenants are often locked into the price trajectory of their original contract, subject to agreed-upon annual increases tied to indices like the cost-of-living index or the company's own operating expenses. The new, lower price for Roitto's former apartment reflects the current market rate for a new contract, a rate dictated by present supply, demand, and competition in the Kallio neighborhood. This creates a two-tier system where new tenants can access better deals than those who have lived in a property for several years.

Broader Context of Finnish Rental Regulations

This case touches on the framework of the Finnish Rental Act, which governs tenancy agreements. The law allows for rent increases under specific conditions, such as when the apartment's reasonable rent level rises due to market changes or when the landlord's maintenance costs increase substantially. It does not, however, mandate rent decreases if the market cools. The responsibility falls on the tenant to negotiate or, ultimately, to terminate the contract and seek a new one—a process that involves cost, effort, and risk. This places the onus on renters to actively monitor the market and be willing to move to secure a fair price, a significant burden that affects housing stability.

The Tenant's Perspective and Calculated Moves

From the tenant's viewpoint, this dynamic forces a constant evaluation. Is the cost and hassle of moving—including deposits, moving services, and potential overlap in rents—worth the potential monthly savings? For Ida Roitto, the discovery of the new lower price confirmed her decision, but also underscored a sense of disappointment. She had paid a higher rate based on a market assessment from months prior, while a new applicant could now secure the same space for less. This scenario discourages long-term tenancy and encourages a churn of residents, which has social and community costs alongside the financial calculations of individual households.