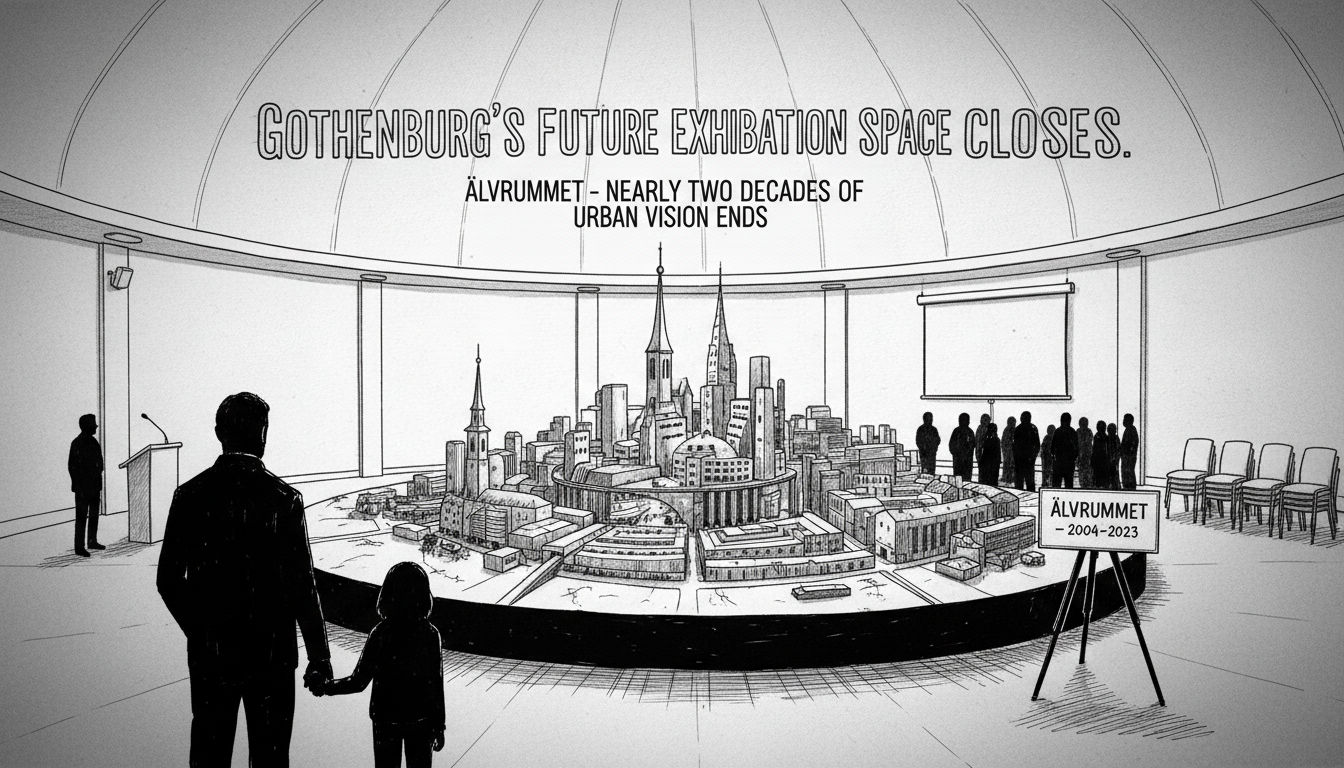

Gothenburg's prominent urban development exhibition space has closed its doors permanently. The Älvrummet facility ended operations after nearly 20 years of showcasing the city's future vision. The closure marks the end of an era for public engagement in urban planning.

The exhibition space first opened in the mid-2000s in a bunker-like building at Lilla Bommen. Its central feature was a massive 30-square-meter model displaying Gothenburg's development around the river. The space served as a vital communication bridge between city developers and residents.

Glenn Evans, who worked as a guide since the beginning, recalled the early challenges. "It took time to gain momentum," Evans explained. "Then former politician Göran Johansson pushed to place the Gothenburg Wheel outside our facility. That decision brought nearly 100,000 annual visitors because we handled ticket sales inside Älvrummet."

The space opened in 2008, shortly after the Götatunnel inauguration. Many residents initially confused the building with tunnel ventilation infrastructure. Evans described the core mission as keeping citizens informed while encouraging dialogue about urban development ideas.

Soup lunches with lectures formed the backbone of Älvrummet's community engagement. Some proposed projects never materialized, like the cable car public transport system. Other developments faced initial skepticism but ultimately succeeded.

"Many people doubted the Karla Tower project," Evans remembered. "I recall when Ola Serneke presented it during an early soup lunch to a packed audience at Kanaltorget. Skeptical attendees sat with crossed arms and laughed. Now the tower stands completed, proving him right."

Communications manager Maria Karlsson expressed mixed emotions during the final soup lunch event. "We feel both pride in honoring Älvrummet's long service and sadness about its closure," she told attendees. About fifty people gathered for the farewell event, which marked the end of guided tours and school visits.

The 2017 relocation to Lindholmen continued offering spontaneous visits and booked tours. Visitors explored both the detailed city model and the actual development areas. All operations have now ceased, leaving hired guides without employment.

Piet De Boer, one of the longtime guides, acknowledged the personal impact. "It feels tough, of course," he said.

Visitors frequently admired the extensive city model featuring wooden miniatures of existing buildings and polystyrene models of future projects. The Karla Tower representation remained in polystyrene despite the completed construction because bankruptcy proceedings prevented obtaining proper blueprints for model builders.

Karlsson explained the closure resulted from new ownership directives. The parent company no longer focuses on urban development activities. "There's a winding-down plan for the company," she noted. "Until then, we'll operate purely as a property management firm."

The closure leaves a significant gap in Gothenburg's public engagement landscape. City developers hoped another municipal entity would continue the exhibition concept. That transfer now appears unlikely, though officials hope the city will eventually offer similar public information services.

Urban planning experts note that such public exhibition spaces play crucial roles in modern city development. They create understanding about urban transformations while fostering community dialogue. These spaces help build collective identity, future optimism, and civic pride among residents. They also inspire career choices in urban development fields.

The loss of Älvrummet represents more than just closing a physical space. It removes a key platform for citizen participation in shaping Gothenburg's future. The challenge now falls to city officials to develop new methods for maintaining public engagement in urban planning decisions.