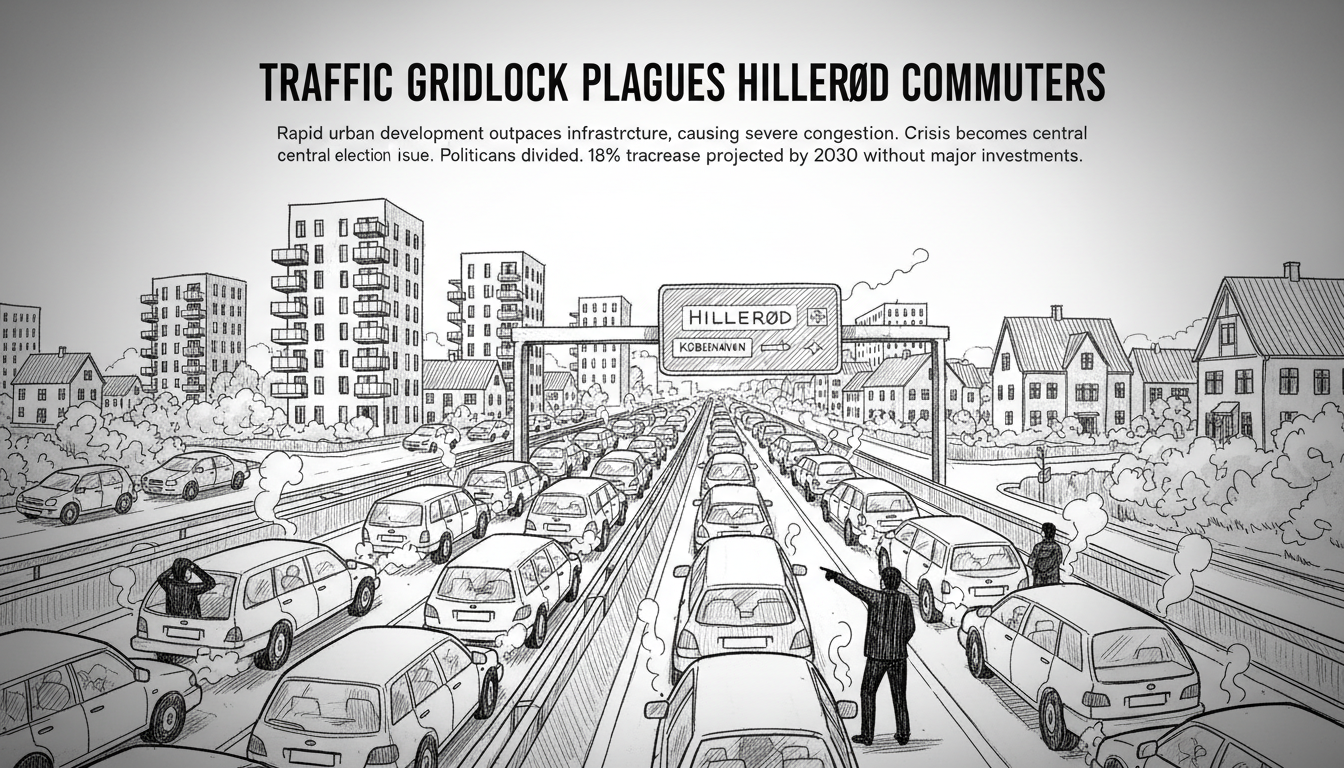

Press the accelerator. Drive 10 meters. Hit the brakes. Wait. Drive five meters. Hit the brakes. Wait again. This frustrating stop-and-go pattern defines the daily commute for thousands of drivers in Hillerød, where traffic congestion has reached crisis levels during morning and afternoon rush hours.

The North Zealand provincial town faces severe traffic problems that have become a central issue in local elections. Recent polling shows transportation concerns top the list of voter priorities for the upcoming municipal election.

Local politician Dan Riise, chairman of the Architecture, Urban Planning and Traffic Committee, describes the situation bluntly. "It has become much worse. We have to face that reality. It's a disaster to put it plainly. We sit in queues, particularly in the western part where the large factories are located. It's completely gridlocked."

The traffic nightmare stems from rapid urban development that outpaced infrastructure planning. Major employers like Novo Nordisk and Fujifilm have created thousands of new jobs in recent years. Simultaneously, new housing developments and educational institutions have opened throughout the municipality.

Traffic researcher Otto Anker Nielsen, a professor at DTU who analyzed Hillerød's congestion problems, explains the core issue. "The road network isn't built large enough relative to the urban development that has occurred. When comparing to other similar suburbs and towns in the capital region, Hillerød ranks among the worst places. If not the worst."

The professor places responsibility squarely on municipal leadership. "It's a municipal responsibility to plan urban development and municipal roads. The current situation reflects planning failures."

Political divisions complicate solutions. The recent budget agreement allocates funds for new bike paths, roads and bus lanes over the next four years. But politicians disagree about which investments should take priority.

The Left Party's Dan Riise advocates spending up to 140 million kroner expanding the busiest roads, particularly those passing Novo Nordisk and leading out of town. He believes this would relieve pressure from the many car commuters traveling to and from work in Hillerød.

Meanwhile, the Red-Green Alliance prefers investing in bicycle infrastructure rather than road expansion. Local council member Tue Tortzen explains, "The inner city was built for horse carriages, and many roads in Hillerød cannot be made wider or longer. That's just how it is, whether one likes it or not."

Novo Nordisk recently received municipal permission to build its own access road to the Hillerød factory for employees, attempting to reduce congestion. But traffic experts question whether piecemeal solutions can address the systemic problem.

A COWI analysis prepared for Novo Nordisk projects traffic in Hillerød will increase by over 18 percent by 2030. Professor Nielsen warns, "I believe congestion will increase. In four years, when we face another municipal election, there will likely be more congestion in the western part of town. Unless they really commit to investments in both road and bicycle networks."

Mayor Kirsten Jensen acknowledges current measures fall short. "We need to invest somewhat more to solve the problems. There are many good things happening, but they don't solve all the problems, and that's what we need to continue working on."

The situation highlights a common challenge across Nordic municipalities: balancing economic growth with infrastructure development. As companies expand and populations grow, transportation systems often struggle to keep pace. Hillerød's traffic crisis serves as a cautionary tale for other developing suburban centers facing similar pressures.

No comprehensive cost estimate exists for solving Hillerød's traffic problems, leaving voters uncertain about the financial implications of proposed solutions. With commuters spending increasing time stuck in traffic, the pressure on local politicians to deliver workable solutions continues to mount daily.