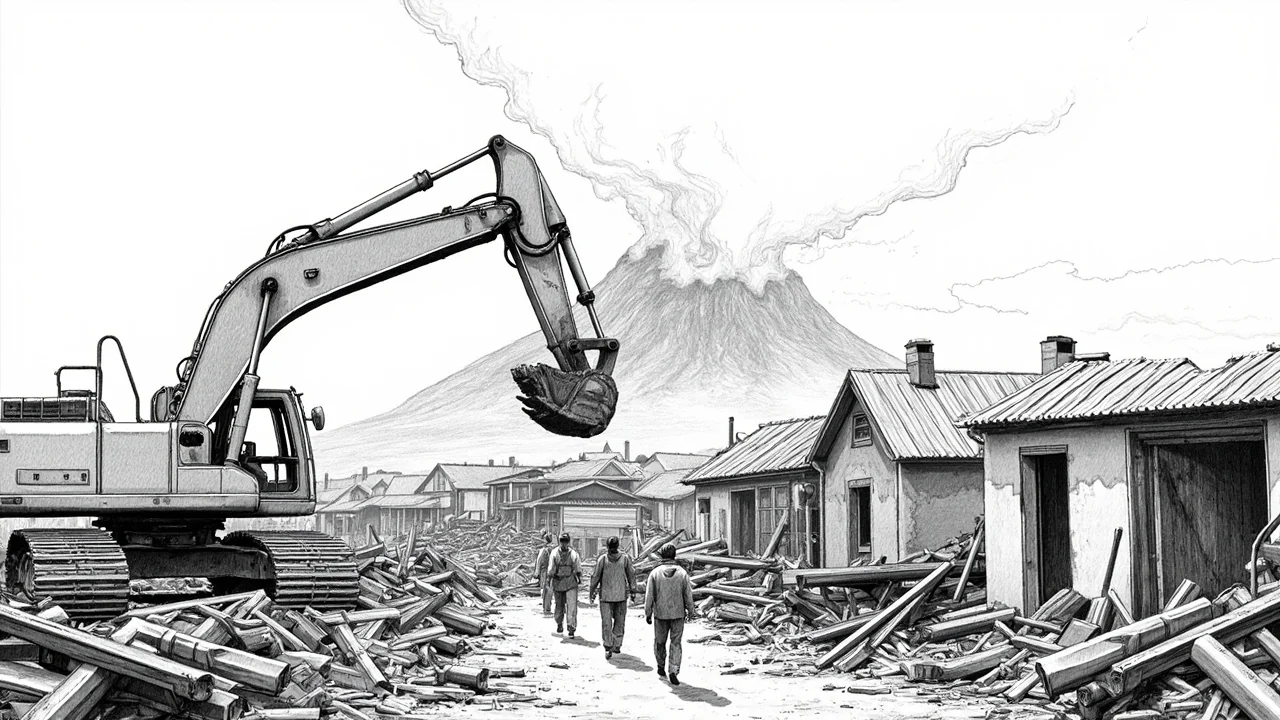

Iceland's Grindavík town council has approved the demolition of 30 to 40 homes destroyed by volcanic eruptions. The first three houses will be torn down in the coming weeks. This marks a pivotal, emotionally charged step in the town's long recovery from the Reykjanes peninsula seismic crisis.

"This is a difficult matter. There are strong feelings underlying this. These are people's properties, which in some cases they built themselves. This is the situation we face now," said Ásrún Kristinsdóttir, President of the Grindavík Town Council. She described the moment as one of "incredibly mixed emotions," acknowledging the pain of loss while recognizing the necessity of the demolitions to begin the town's reconstruction.

A Town Between Grief and Renewal

The decision to systematically remove the damaged structures follows years of uncertainty. The homes, primarily located near Mánasund and Mánagata, were rendered uninhabitable by ground deformation, earthquakes, and lava flows. For many residents, the demolition order provides a grim finality, replacing damaged property with empty plots. It also represents the first concrete action toward rebuilding the community's physical fabric. The council will manage the process through a fast-track tender system this month, aiming for efficiency while navigating complex insurance and compensation landscapes.

Environmental analysts note the demolitions must address unique hazards. Structures may be contaminated by volcanic gases or compromised by unstable ground. "This isn't standard urban renewal," said a geologist familiar with the site, speaking on background. "They're dealing with a landscape fundamentally altered by geothermal forces. Every demolition and subsequent construction plan requires a fresh geological assessment." The process sets a precedent for Iceland in managing large-scale property loss directly caused by volcanic activity.

The Political and Economic Fault Lines

The Grindavík crisis has dominated the Althing, Iceland's parliament, forcing debates on national responsibility for localized natural disasters. Members from the Progressive and Independence parties have pushed for accelerated state funding, while the Left-Green Movement emphasizes long-term, sustainable planning for the entire Reykjanes region. The cost of demolition, cleanup, and future rebuilding will strain both municipal and national budgets.

"This is where policy meets reality," said MP Birgir Ármannsson, whose constituency includes the south coast. "We have families who have lost everything, a key fishing industry disrupted, and a national landmark community in peril. The government's response to Grindavík's reconstruction will be a benchmark for its crisis management capability." The government has established special task forces, but residents complain of bureaucratic delays in releasing promised aid.

The fishing industry, the town's economic backbone, faces parallel challenges. While the harbor was spared from lava, the loss of population and housing for workers creates operational headaches. Processing plants run below capacity. The demolitions, therefore, are not just about homes but about restoring the entire economic ecosystem of a community that contributes significantly to Iceland's export economy.

A Nordic Perspective on Disaster Recovery

Iceland's situation draws attention from its Nordic neighbors, who observe with professional interest. Norway has extensive experience with managed retreat from unstable slopes, while Sweden and Finland have protocols for post-disaster urban planning. Denmark's expertise in coastal protection against storms offers different, but relevant, insights. However, none have a direct template for recovery from repeated volcanic eruptions in a modern town.

Nordic cooperation mechanisms, like the Nordic Council of Ministers, have facilitated knowledge exchange. Icelandic civil protection officials have studied landslide responses in Norway and flood recovery in Denmark. "The Nordic model is built on solidarity," said a Danish emergency planner. "But Grindavík is a uniquely Icelandic tragedy. Their path to recovery will be one they largely forge themselves, with our technical support." This event tests the limits of regional preparedness frameworks designed for more common disasters.

The Human Cost of a Volcanic Crisis

Behind the council's decision and the political debates are hundreds of displaced residents. Some have moved to temporary housing in Reykjavík's suburbs like Grafarvogur or Kópavogur. Others remain in the wider Suðurnes region, hoping to return. The demolition of their homes removes a physical anchor, deepening a sense of permanent loss. Community groups have organized counseling services, recognizing that the psychological impact of the eruptions will outlast the geological activity.

For the town council, led by Ásrún Kristinsdóttir, the demolition phase is an administrative and emotional tightrope. They must enforce public safety by removing dangerous structures while honoring the memories and investments those homes represent. "It is of course gratifying to have reached this point," Ásrún stated, highlighting the paradoxical relief of moving forward. "And we need to continue on this journey." Her wording captures the town's dilemma: progress is essential, but it is paved with personal ruin.

What Comes After the Rubble is Cleared?

The cleared plots pose the next major question. Will they be rezoned? Sold back to original owners? Converted to public space as a buffer against future seismic zones? The town's master plan is under total revision. Ideas include building more resilient housing types, creating expanded geothermal energy infrastructure to harness the very forces that caused destruction, and redesigning the community layout with evacuation routes as a central feature.

Environmentalists see an opportunity for Grindavík to become a model for climate-resilient towns. Iceland's deep geothermal expertise could be used to create district heating systems even more robust against volcanic interference. The reconstruction could prioritize sustainable materials and energy independence. However, these ambitious visions compete with the urgent need for simple, fast rebuilding to bring people home.

The demolition of 30-40 homes in Grindavík is more than a cleanup operation. It is the first, painful edit of a new chapter in Iceland's relationship with its volatile geology. The world watches as this resilient community, supported by the Althing and its Nordic partners, literally clears the ground to define its future. The success or failure of this effort will resonate far beyond the Reykjanes peninsula, offering lessons for all communities living on the edge of natural forces.