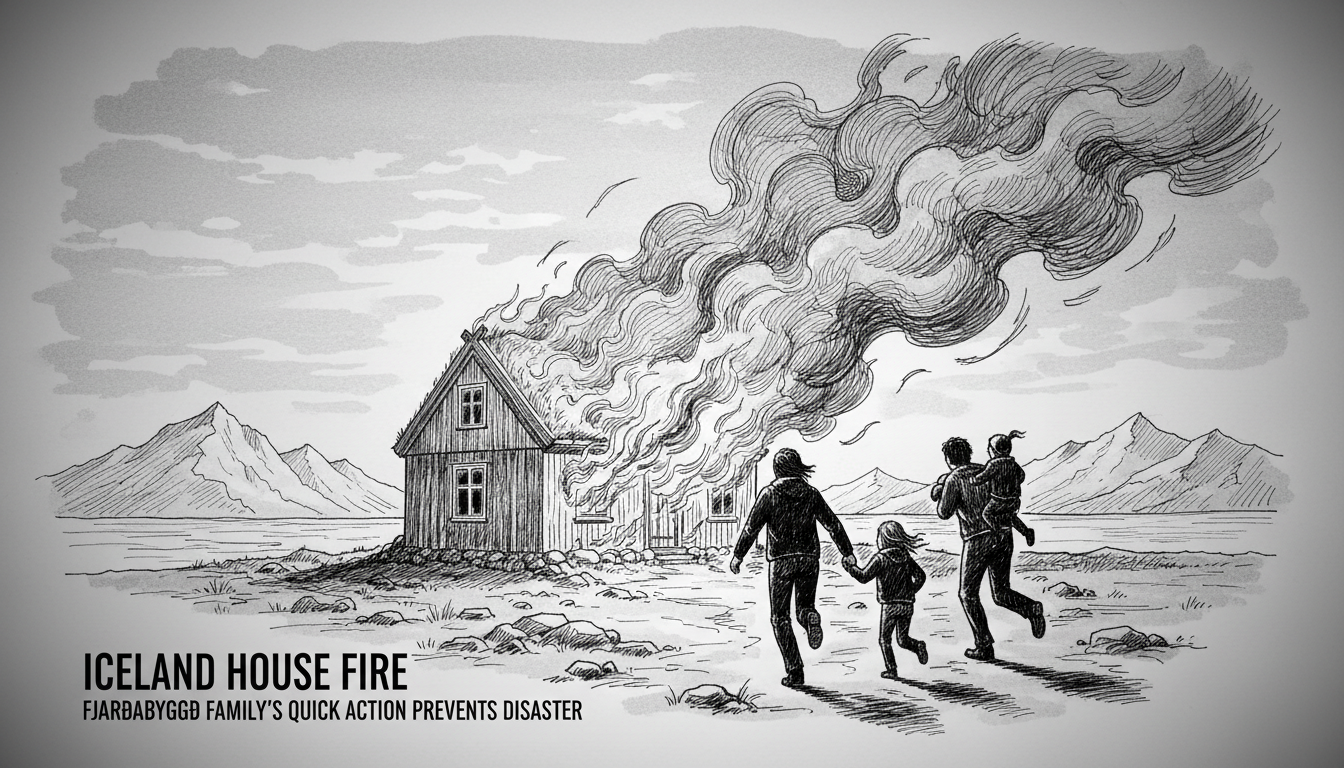

Iceland's Fjarðabyggð fire department received a high-priority call at 2:22 PM yesterday. A pot of oil had ignited in a family home, threatening to escalate into a major blaze. The quick and correct actions of the residents themselves prevented what could have been a tragedy, extinguishing the flames before firefighters even arrived.

When the Slökkvilið Fjarðabyggðar crew reached the single-family house, the main fire was out. Intense heat still radiated from the kitchen, with small embers smoldering within a wall. Firefighters spent the next hour and a half cooling the structure, ensuring no hidden fire remained, and ventilating smoke. Operations concluded by 4:00 PM. "The outcome was better than it first appeared," the fire department noted, crediting the household's immediate response.

This incident in East Iceland underscores a critical, nationwide reality. Iceland's architectural heritage and challenging climate create unique fire risks. Swift public action is often the most decisive factor in limiting damage and saving lives.

The Anatomy of a Kitchen Fire

Kitchen fires, particularly those involving cooking oil, are among the most common and dangerous domestic blazes in Iceland. Oil reaches extremely high temperatures and can ignite spontaneously. Once aflame, it is highly volatile; throwing water on it can cause explosive splattering, spreading the fire rapidly.

"The first minutes of a fire are everything," says Helgi Jónsson, a veteran fire safety instructor based in Reykjavík. "A pot of oil on a stove is a contained fuel source. If you smother it correctly—with a metal lid or a proper fire blanket—you cut off the oxygen and stop it immediately. If you panic or use the wrong method, you can lose the entire kitchen in under three minutes."

In the Fjarðabyggð case, the family's successful suppression points to either prior knowledge or instinctive correct action. Their intervention meant firefighters faced a secure and cooling scene rather than an active inferno. This distinction is crucial in Iceland's often remote municipalities, where response times can be longer than in urban centers like Reykjavík's 101 district.

Iceland's Built Environment and Fire Risk

Fjarðabyggð itself is a testament to Iceland's dispersed population and building trends. Formed in 2006 from the merger of several smaller communities along the eastern fjords, it encompasses both clustered towns and isolated homes. The prevalence of wooden structures, chosen for their resilience to seismic activity and historical availability, is a double-edged sword. While aesthetically fitting and durable, wood is a ready fuel source.

"We have a beautiful but vulnerable building stock," explains Anna Þórhallsdóttir, a civil engineer specializing in building codes. "Many older homes, and even newer ones in rural areas, are timber-framed. Modern regulations require better fire-stopping materials in walls and around chimneys, but the core material remains combustible. This makes early detection and suppression not just advisable, but essential."

Iceland's harsh weather compounds the risk. During long, dark winters, reliance on indoor heating—from geothermal radiators to electrical systems—increases. The high winds common in coastal areas like the Eastfjords can turn a small structural fire into a wind-whipped conflagration that challenges even well-equipped fire crews.

The Critical Role of Public Preparedness

The positive outcome in Fjarðabyggð aligns perfectly with the core message of Iceland's fire safety authorities: the public are the true first responders. The Icelandic Association for Search and Rescue (ICE-SAR), which works closely with professional fire services, consistently emphasizes preparedness.

"We train thousands of volunteers every year, and a key module is basic fire response for the home," says a regional ICE-SAR coordinator. "It's about simple knowledge: Have a working fire extinguisher and blanket in your kitchen. Test your smoke alarms monthly. Know how to shut off your main power and heating sources. And never, ever fight a fire that is spreading beyond its initial source—your priority then is to get out and call for help."

This layered defense strategy is vital. The professional fire service forms the last line of defense, but an informed populace creates the first and most effective barrier. National statistics show that in over 60% of residential fires where serious injury or death is avoided, a civilian intervention occurred before emergency services arrived.

A Nordic Model of Response and Cooperation

Iceland's approach to emergency management is deeply integrated into the Nordic cooperative framework. While each municipality operates its own fire service, standards, training protocols, and major incident responses are coordinated nationally. In crises exceeding local capacity, resources can be mobilized from other regions, or even from neighboring Nordic nations under mutual aid agreements.

This system was tested during the 2022 Fagradalsfjall volcanic eruption near Grindavík, where fire crews from across the country assisted with protecting infrastructure. For structural fires, the principle is the same, albeit on a smaller scale. The Fjarðabyggð crew, though dealing with a contained incident, operates within this web of shared knowledge and resources.

"We learn from each other," says the chief of the Fjarðabyggð fire department. "After an incident, we share reports. If a particular type of kitchen appliance is causing recurring issues in one town, that information is circulated nationwide. Our goal is prevention first, effective response second."

Looking Ahead: Prevention in a Changing Climate

The conversation around fire safety in Iceland is increasingly intersecting with climate change. Drier summers, predicted by the Icelandic Meteorological Office, could elevate the risk of wildfires in heathland and forested areas, which in turn threaten communities. This places even greater importance on creating defensible space around properties and updating community evacuation plans.

For indoor fires, the focus remains on education and technology. Campaigns to install more heat alarms alongside smoke detectors, especially in kitchens and boiler rooms, are gaining traction. There is also a push to incorporate automatic fire suppression systems, like sprinklers, into the building codes for new multi-family dwellings and commercial structures.

Yet, as yesterday's event proves, technology is only an aid. The human element remains paramount. The family in Fjarðabyggð, facing a sudden and terrifying situation, acted correctly. Their calm response saved their home and potentially their lives. It served as a powerful, real-life demonstration of a principle every Icelander is taught: in the land of fire and ice, knowing how to handle fire is not just useful—it is a fundamental skill for modern living. How many other households are one pan of oil away from testing that knowledge?