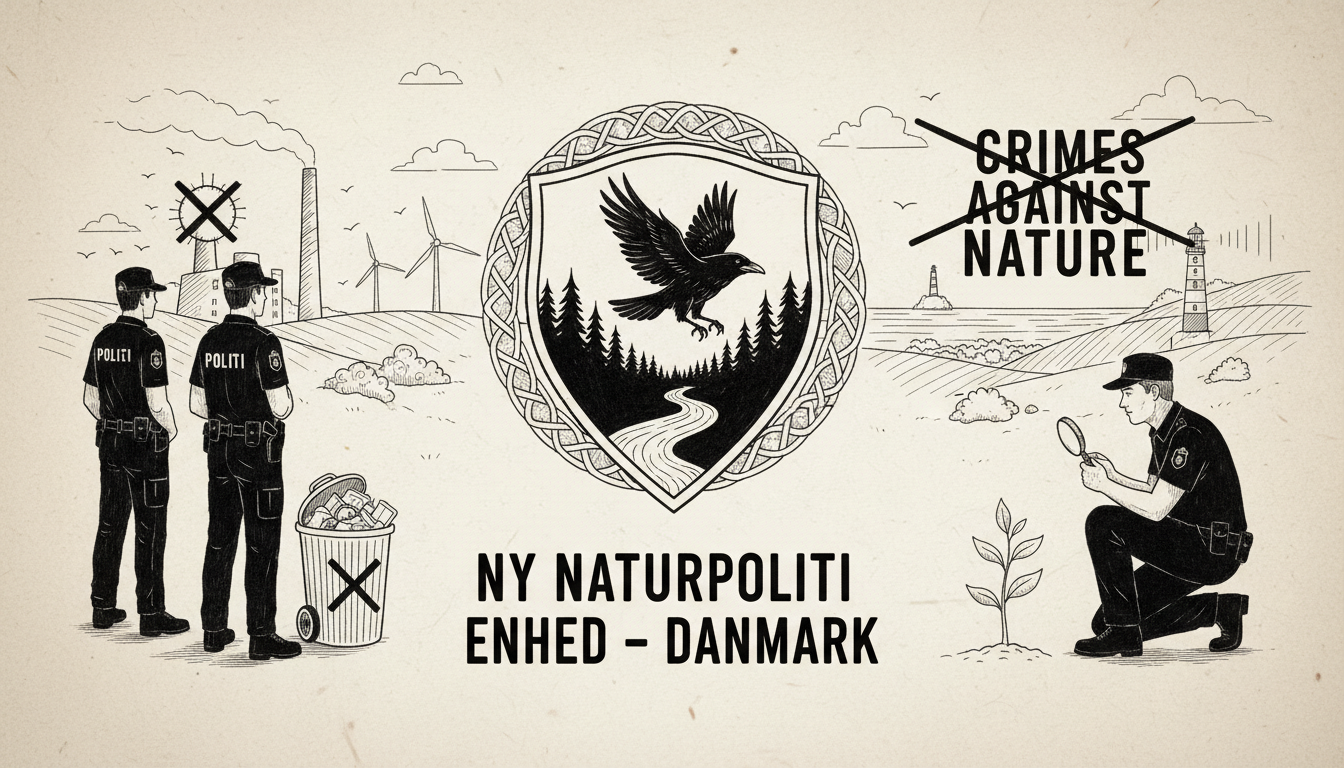

A new specialized police unit will soon focus on solving crimes against nature and the environment in Denmark. The unit is part of a new police agreement backed by a majority of parties in the Danish parliament. It aims to address what officials call a growing problem of both small and large-scale violations against protected natural areas. The move reflects a broader shift in Danish society news, where environmental protection is gaining equal footing with traditional law enforcement priorities.

Karina Lorentzen, a legal affairs spokesperson for the Socialist People's Party, has long advocated for such a unit. She says the most important outcome is creating real consequences for damaging nature. Many offenses currently go unreported or unpunished, she argues, which clashes with national goals to expand natural habitats. Lorentzen points to specific cases, like a destroyed protected bog at Donssøerne near Kolding and unauthorized earthmoving at a protected coastal stretch in Brejning, as examples of the complex cases the unit will handle.

The political agreement allocates 10 million Danish kroner annually until 2030 to fund the unit. It will consist of twelve full-time positions, including specialized police officers and dedicated prosecutors. This structure is designed to build deep expertise in environmental law, a field often deprioritized in standard police work. The funding commitment signals a serious political intent to elevate these cases within the Danish welfare system's framework of justice.

Local officials in municipalities that have dealt with such crimes welcome the initiative. Jørn Chemnitz, chairman of the Nature, Environment, and Climate Committee in Kolding Municipality, is enthusiastic. His municipality spent roughly 260 employee hours on a single case involving the vandalized bog at Donssøerne. That case resulted in a couple receiving a four-month suspended sentence and 100 hours of community service. Chemnitz estimates the new unit could save local authorities 30 to 40 percent of the time spent on such investigations. He says municipal workers would rather focus on constructive tasks than lengthy legal procedures.

The hope is that a dedicated state-level unit will encourage more municipalities to report violations. Lorentzen admits many local governments currently avoid filing police reports. They fear the process will be too burdensome and may lead nowhere. A specialized unit with guaranteed expertise should provide reassurance. It should make reporting seem worthwhile, thereby increasing the detection rate for environmental crimes. This is a key goal for Copenhagen integration of environmental policy into broader societal governance.

This policy development connects to wider trends in Denmark social policy, where local municipal burdens and state-level resources are constantly balanced. The creation of a niche police force highlights how environmental regulation is becoming more formalized and judicial. It moves beyond simple administrative fines. For international observers, it shows Denmark's approach to enforcing its ambitious green transition. The state is building a legal backbone to match its political declarations on nature. The real test will be whether the unit's work visibly deters future offenses and protects vulnerable ecosystems across the country.