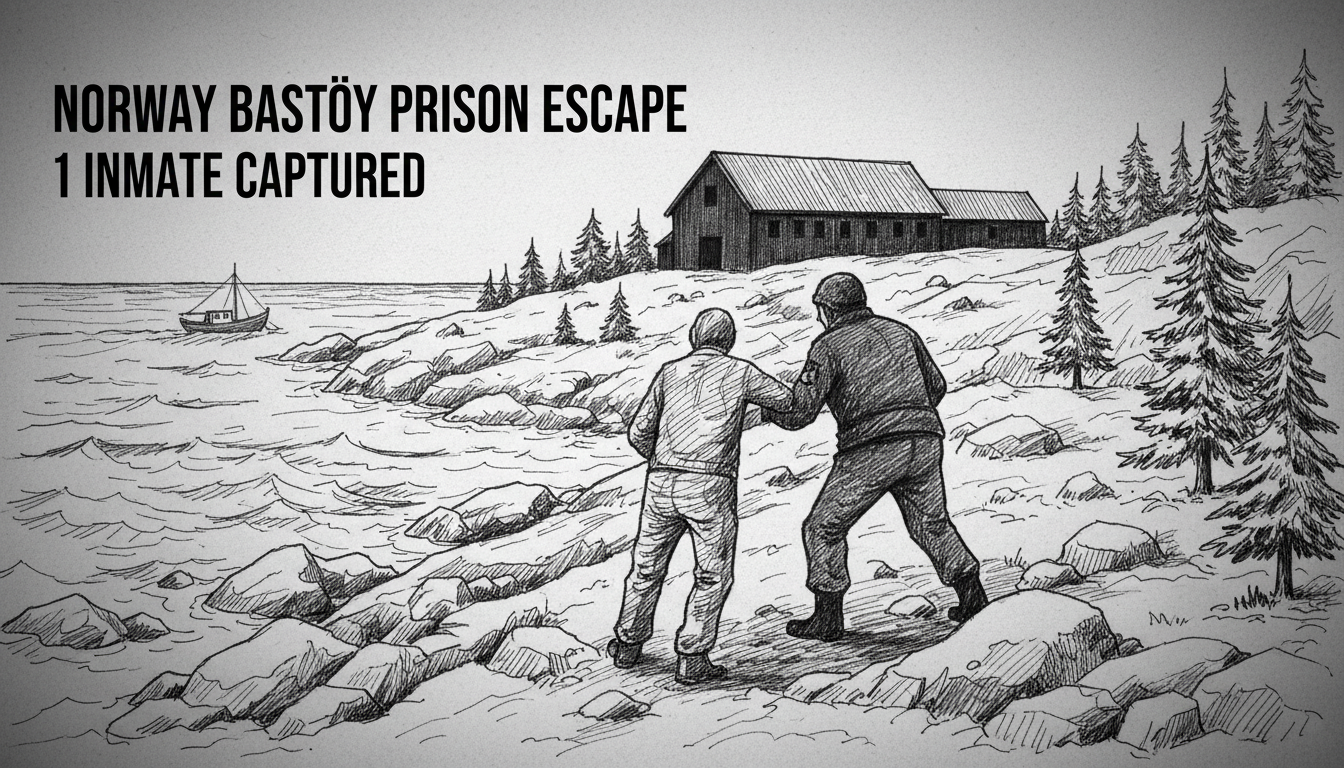

Norwegian authorities are processing the extradition of an inmate who escaped the country's iconic open prison, Bastøy, only to be captured in Sweden days later. The incident has reignited a perennial debate about the balance between rehabilitation and security within Norway’s famously humane correctional system. The Serbian national, in his thirties, was reported missing from the island prison in the Oslofjord on the evening of October 26th. He had just a few months remaining on his sentence when he disappeared. A search of the island that lasted several hours proved futile. By Monday, police confirmed the man was in custody in Sweden on separate charges, and a Nordic arrest warrant had been issued for his return to Norway.

The Escape and Cross-Border Capture

Police prosecutor Jon Inge Engesmo stated that the extradition process is now underway. The man is currently detained in Sweden based on a Swedish case. The reasons for his flight from Bastøy remain unclear. His brief period of freedom ended when Swedish authorities apprehended him. The case highlights the ease of cross-border movement within the Nordic region, even for individuals fleeing justice. For the Oslo Police District, the focus has shifted from a manhunt to bureaucratic procedure, working through the formal mechanisms to return the inmate to Norwegian custody to complete his sentence.

Inside Norway's Controversial Island Prison

Bastøy Prison is no ordinary correctional facility. Housing approximately 115 inmates, it operates as a small, self-sufficient community on a picturesque island. Inmates live in small houses, not cells, and work on the prison's farm, maintaining its grounds and tending to livestock. The regime emphasizes ecological sustainability, personal responsibility, and preparing individuals for a successful return to society. The model is a flagship for the Norwegian penal philosophy, which focuses relentlessly on rehabilitation and normalization. The prison's design and daily operation are intended to mirror life outside as closely as possible, reducing institutionalization and building prosocial habits.

This approach yields measurable results. Recidivism rates for former Bastøy inmates are reportedly significantly lower than the national average. Norway itself boasts one of the lowest re-offending rates and lowest imprisonment rates in all of Europe. Proponents argue that this proves the system's effectiveness in enhancing public safety over the long term, even if its low-security nature carries inherent risks. The prison's gates are not locked, and the perimeter is the cold water of the Oslofjord itself. Escapes, while rare, are a known possibility.

A System Under Scrutiny

Each escape from Bastøy inevitably prompts public and political scrutiny. Critics question whether the model is too permissive, especially for inmates with foreign citizenship and less established ties to Norway. The fact that this inmate fled the country entirely adds a layer of complexity, involving international police cooperation. Supporters of the system counter that occasional escapes are a calculated risk worth taking for the profound societal benefits of lowered re-offending. They stress that the vast majority of inmates honor the trust placed in them, using their time at Bastøy as intended—a final, supervised step toward lawful freedom.

Criminologists often point to Norway's system, and Bastøy specifically, as a global exemplar of humane and effective incarceration. The core belief is that treating inmates with dignity and providing them with skills and responsibility makes them less likely to commit crimes after release. The open prison model is the ultimate expression of this principle. However, it operates on a foundation of mutual trust between the state and the inmate. An escape represents a breach of that trust, forcing a re-examination of the security assessments and processes that lead to an inmate's placement on the island.

The Road Ahead for Norwegian Corrections

The incident comes at a time when prison systems worldwide are grappling with overcrowding, violence, and high recidivism. Norway's alternative model continues to attract international study and praise. The capture of the escaped inmate likely concludes this specific episode without major incident. Yet, it leaves behind familiar questions for the Justice Ministry and correctional service officials. Will this lead to a tightening of criteria for transfer to open prisons like Bastøy? Or will it be viewed as an isolated incident, absorbed as part of the acceptable risk in a system that has demonstrably worked for decades?

The inmate, once extradited, will likely finish his short remaining sentence in a more traditional, closed facility. For the staff and remaining population at Bastøy, operations will continue as normal. The farm work, the maintenance, and the quiet rhythm of life on the island persist. But in Oslo's government buildings and in the public discourse, this escape serves as a periodic stress test for a deeply held national philosophy. It challenges Norway to reaffirm its commitment to rehabilitation, even when that commitment is occasionally met with betrayal. The ultimate question remains: Is a system that allows for the possibility of escape a sign of weakness, or is it the very source of its strength in creating safer communities?