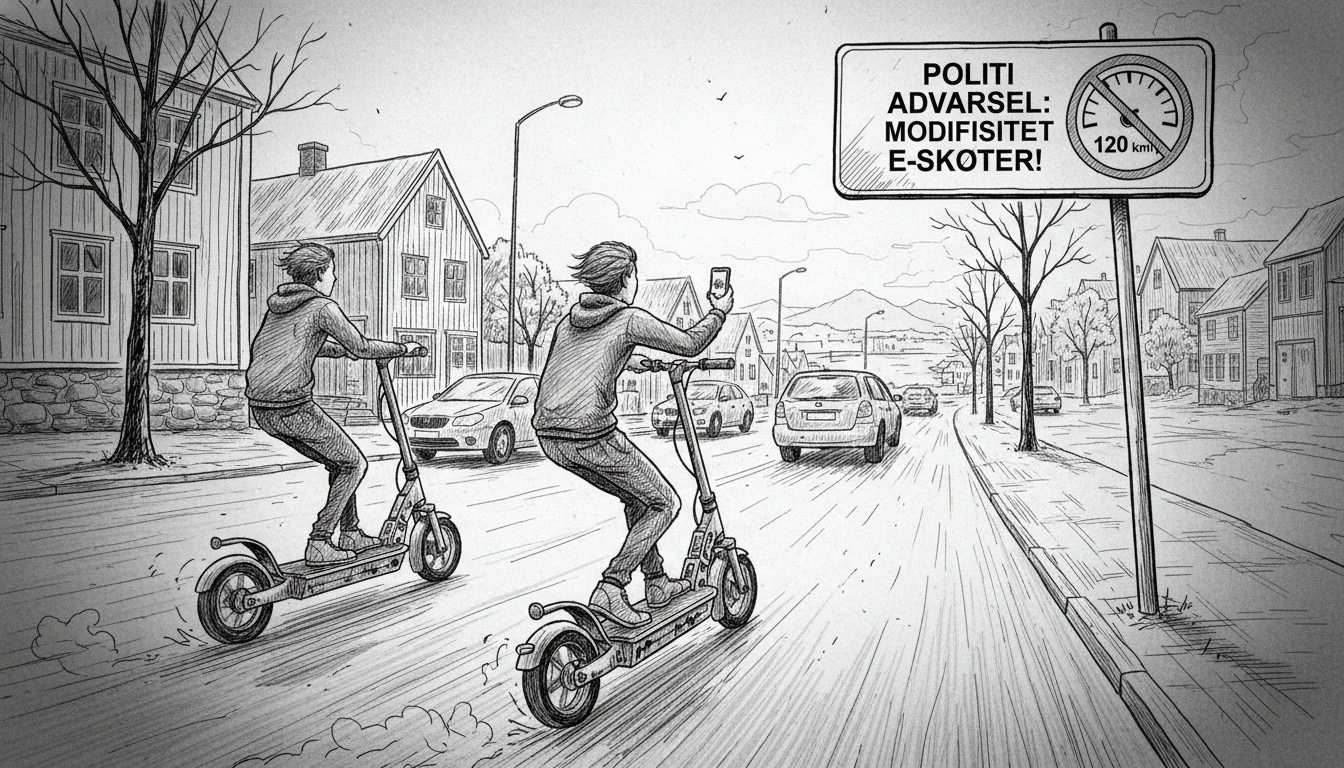

Norwegian police are issuing urgent warnings about teenagers racing modified electric scooters at dangerous speeds. Officers report youth are pushing boundaries with social media as their audience. They chase adrenaline while filming their stunts for TikTok. These riders show little concern for potential consequences.

Adrian Hegge from the Vestfold Emergency Police Unit describes the behavior as madness. He states riders essentially gamble with their lives. Police have recorded speeds reaching 120 kilometers per hour. The margin for error becomes dangerously small at such velocities.

Authorities worry these viral videos inspire copycat behavior. The phenomenon creates a ripple effect across teenage communities. Officers now plead with parents to open their eyes. They want families to discuss the risks before tragedy strikes.

Current e-scooter regulations in Norway require several safety measures. Only one person may ride each scooter. Speed limits cap at 20 km/h regardless of location. Riders must be at least 12 years old. Helmets remain mandatory for children under 15. The blood alcohol limit stands at 0.2 percent. Insurance coverage remains legally required. Using handheld phones while riding is prohibited.

Police face challenges enforcing these rules. Many teenagers attempt to flee from officers. Police often choose not to pursue them. They worry about causing injuries during chases. A warehouse in Vestfold currently stores 13 confiscated e-scooters from the past six months. All exceeded speed limits or were involved in accidents.

Henning Ødegaard Johansen from the Southeast Police District shows one powerful scooter. It reached 110 km/h during testing. Police seized it after two teenagers crashed seriously. The Eastern Police District confiscated 18 likely modified scooters this year. That compares to 13 during the same period last year.

Robert Bjørklund from the Inland Police District confirms increasing numbers there too. He finds the development deeply concerning. Oslo police note many privately owned scooters show modifications. Trond Arvid Olsen from Oslo's operational special functions says speeding appears more normal than compliance.

Modified scooters range dramatically in capability. Larger models can reach 40-140 km/h. Smaller 5,000-6,000 kroner models might hit 30 km/h after modification. Teens find modification methods online. Some manufacturers provide apps to remove restrictions. Others require physically removing cables.

Adrian Hegge urges parents to research their children's scooters. They should understand the technical specifications. Parents cannot visually identify modified scooters. They need to test ride them. Speedometers often reveal the truth. Hegge suggests parents observe their children riding.

At Gjøklep Middle School in Holmestrand, modification awareness runs high. Some students ignore the issue. Others find it somewhat cool. Student council member Sondre Stormorken believes perceived coolness drives the trend. He and council leader Zuhra Hussain ride compliant scooters. Stormorken received strict instructions from his parents about helmet use and non-modification.

Police want more families to have these conversations. Children need clear messages about modification dangers and passenger limits. Henning Johansen recommends concrete agreements between parents and children. Breaking traffic rules should mean losing scooter privileges. He stresses consequences must follow violations. The current accident trend cannot continue unchecked.

The e-scooter modification phenomenon reflects broader issues with teen risk-taking and social media influence. Norway's generally safe roads now face new challenges from these easily modified vehicles. Parents struggle to monitor technology that changes rapidly. The situation requires balancing teen independence with realistic safety measures. Police resources strain to address what becomes essentially a digital-age public safety concern.