Sweden is training over 1,000 new search volunteers to find missing persons by partnering with the country’s top orienteering experts. A new digital training program, developed over the last six months, aims to equip civilian volunteers with crucial map and compass skills often missing during critical searches.

Every year, hundreds of people vanish in Sweden's vast forests and urban areas. The first response often relies on local volunteers. Many arrive with warm hearts but empty hands when it comes to navigation. 'You see people showing up in sneakers for a forest search, or with no idea how to read the terrain,' says Lars Bengtsson, a Stockholm-based orienteering coach involved in the new program. 'Goodwill is not enough. We can fix that.'

The Search Skills Gap

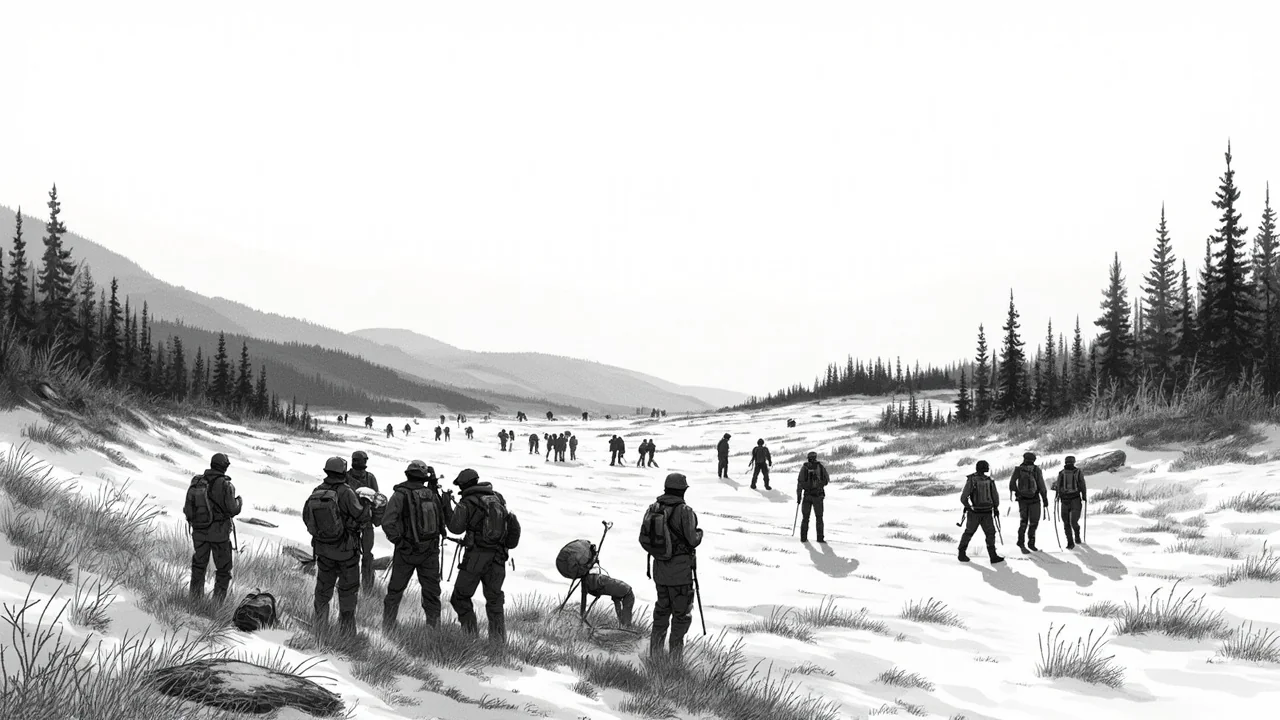

When a person goes missing, time is the enemy. Police coordinate large-scale operations, but they depend on supplementary volunteers for ground coverage. The current system has a weak spot. Many volunteers lack basic knowledge about proper clothing, equipment, and—most critically—navigation. In a nation where forests cover nearly 70% of the land, being able to use a map and compass is not a hobbyist skill. It is a lifeline.

The new initiative directly tackles this gap. Orienteering clubs across the country, from Malmö to Kiruna, are now formal partners with missing persons organizations. Their collective expertise in moving efficiently through complex terrain is being channeled into a structured curriculum. The training moves beyond theory. It focuses on practical skills a volunteer needs when entering a search grid: how to track their position, mark searched areas, and communicate findings accurately.

From Forest Trails to Rescue Missions

Orienteering, or 'orientering', is deeply woven into Swedish culture. It is a national sport taught in schools, blending cross-country running with advanced navigation. For Swedes, it’s as much a part of childhood as learning to swim. 'We grow up with maps,' explains Elin Forsberg, a champion orienteer from Uppsala. 'It teaches you to see the landscape differently—a contour line, a rock feature, the density of a pine stand. These are the clues that matter when someone is lost.'

The collaboration makes profound sense. Orienteering clubs have the knowledge and the community networks. Missing persons groups have the urgent, real-world application. The six-month pilot phase worked out the logistics. Now, the digital training platform scales up the effort. Volunteers can learn core concepts online before attending practical field sessions in local forests, like those in Nacka or Djurgården in Stockholm.

A Digital Compass for Modern Searches

The digital course is key to wide reach. It covers fundamentals from dressing in layers for Sweden's unpredictable weather to essential gear like headlamps and whistles. The core module, however, is navigation. Using interactive maps and simulations, it teaches how to orient a map, take a bearing, and triangulate a position. 'It’s about building confidence,' says Bengtsson. 'When you're in a stressful situation, you need these skills to be automatic.'

This approach also respects the volunteers' time. People can complete modules at their own pace, making it easier for working professionals or students to participate. The goal is to create a large, prepared reserve force. These volunteers can be activated quickly, no matter where in Sweden a person disappears.

Cultural Roots in Practical Help

This project reflects a broader Swedish principle: 'duktig', or being capable and resourceful. There is a strong cultural expectation of practical competence and civic contribution. The 'allemansrätten'—the right of public access—grants everyone freedom to roam the countryside. With that right comes an implicit responsibility. This training formalizes that responsibility, turning general goodwill into specific, life-saving ability.

I spoke with Mia Karlsson, who volunteered in a search in Sörmland last autumn. 'I wanted to help, but I felt useless,' she admits. 'Others had compasses and knew the grid patterns. I just followed. I’ve now taken the new course. Next time, I will be an asset, not just an extra body.' Her sentiment is common. The training empowers people to transform anxiety into effective action.

Analysis: A Model for Civic Response

This partnership is a smart, low-cost innovation in public safety. It leverages existing community structures—the nationwide network of orienteering clubs—to solve a clear problem. No new large bureaucracy was created. Instead, two groups with complementary skills found common cause.

Experts see potential for this model beyond Sweden. 'Many Nordic countries have similar outdoor cultures and volunteer traditions,' notes sociologist Dr. Henrik Lundström. 'Sweden’s solution connects civic duty with concrete education. It strengthens social cohesion while directly improving emergency response. It’s a powerful combination.'

The challenge now is uptake. Promoting the program and ensuring it reaches beyond the typical outdoorsy demographic is crucial. Organizers are targeting urban centers like Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö, using social media and community events to recruit a diverse volunteer base.

The Human Map Forward

The true test will come with the next call for volunteers. The hope is that the response will be not just larger, but smarter. Prepared volunteers mean searches can be more systematic, cover more ground, and end with better outcomes. In a country where the distance between a cozy suburb and a vast wilderness can be a short bus ride, that preparedness is everything.

This story is not just about maps and compasses. It is about a society organizing its own kindness, structuring its compassion with competence. As the days grow longer and more people head into the woods, that competence could be what brings someone home. The next time the alert goes out, the volunteers will be ready. They will not just be searching. They will be navigating.