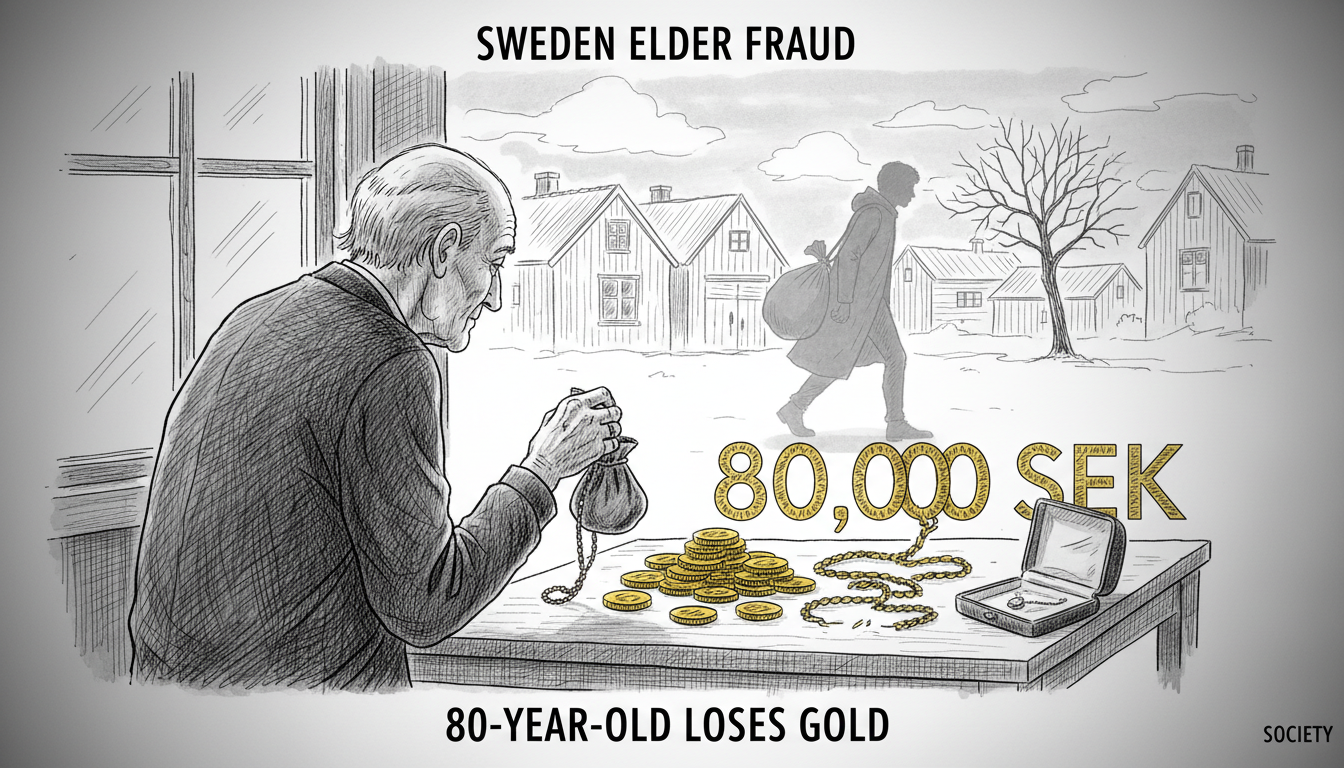

Sweden elder fraud has struck again in an affluent Stockholm suburb. An 80-year-old woman in Täby was tricked out of gold worth 80,000 Swedish kronor by men posing as cleaners. The incident is part of a disturbing pattern of 'åldringsbrott' targeting vulnerable seniors across the capital region.

Several unknown men deceived the woman during the afternoon. They arrived at her home claiming to be from a cleaning company frequently hired by elderly residents. The men were not from the company. They instead manipulated the woman and stole her gold. Police have registered a report for aggravated fraud, known as 'grovt bedrägeri'.

Authorities confirm a similar fraud occurred on Södermalm in central Stockholm that same morning. Several other attempted scams have been detected recently in the area. This indicates an organized effort to prey on older citizens.

A Calculated Deception

The scam follows a familiar and effective script. Perpetrators pose as trustworthy service providers. They often target areas with higher concentrations of elderly residents living alone. Täby, north of Stockholm, is one such affluent residential municipality. Södermalm, with its mix of older apartments and younger residents, provides another target-rich environment for fraudsters.

"These criminals exploit fundamental human trust," says Karin Lundström, a criminologist specializing in fraud prevention. "They present themselves as helpful, as part of a known service. For an older person, especially one who might use cleaning services, this can seem perfectly logical. The barrier to letting them in is lowered dramatically."

The emotional impact on victims is severe. Beyond the significant financial loss, there is a profound sense of violation and shaken trust. Victims often report feeling ashamed and hesitant to report the crime, fearing they will be seen as incapable.

A Persistent and Growing Problem

Elder fraud is not a new phenomenon in Sweden. The National Council for Crime Prevention (Brottsförebyggande rådet, Brå) has tracked these crimes for years. Reports fluctuate but consistently show a vulnerable population at risk. Police districts across Sweden run recurring awareness campaigns, particularly in communities with older demographics.

Prosecuting these crimes presents major challenges. Assets like gold are quickly liquidated. Perpetrators are often transient or part of broader criminal networks. The conviction rate for 'åldringsbrott' is difficult to pinpoint, but recovery of stolen property is rare. This makes prevention the most critical tool.

"We see these waves of activity," a Stockholm police spokesperson said in a statement regarding the Täby and Södermalm cases. "A group will identify a method that works and exploit it until awareness increases or we can make an arrest. Public vigilance is our best ally. If an offer or service visit seems unscheduled or suspicious, verify it independently before allowing access."

The Mechanics of Prevention

Experts stress a multi-layered approach to protection. Family involvement is the first line of defense. Regular check-ins and open conversations about potential scams can build resilience. Community networks are equally vital. Neighbors, building custodians, and local shopkeepers can often spot unusual activity.

Financial institutions also play a key role. Banks have protocols for spotting suspicious transactions, especially large cash withdrawals or transfers by elderly clients. Training for bank staff to recognize the signs of coercion or deception is an ongoing effort.

"We need to move from individual responsibility to a community shield," argues Lars Bengtsson, who leads a non-profit focused on elder safety. "The responsibility cannot lie with an 80-year-old to detect a sophisticated liar at their door. It lies with their family to talk to them, with their neighbors to watch their home, and with local banks to have safeguards. Isolation is the fraudster's greatest weapon."

Simple, practical steps are highly effective. These include installing chain locks or video doorbells to allow verification without opening the door fully. A printed list by the telephone of trusted family members and verified company numbers is also recommended. The golden rule, repeated by all authorities, is never to let an unscheduled, unverified stranger into your home.

Beyond the Financial Loss

The theft of 80,000 SEK in gold is a substantial blow. For many pensioners, this represents a life's savings held in a tangible asset. Gold is often chosen for its perceived stability and ease of storage. Its theft is not just a crime against property, but against future security and peace of mind.

These crimes also carry a significant social cost. They foster fear and suspicion among older adults, potentially leading to further social withdrawal. They can accelerate decisions to leave independent living for assisted facilities, not out of need, but out of fear.

The police investigation into the Täby and Södermalm incidents is ongoing. Authorities are likely reviewing local CCTV footage and appealing for witnesses. The classification as 'grovt bedrägeri' means it is being treated with high priority, carrying a potential prison sentence of up to six years.

A Societal Test

The repeated occurrence of these scams poses a quiet test for Swedish society. Sweden prides itself on a high-trust social model and a strong welfare state designed to protect its citizens. Targeted fraud against the elderly directly challenges that foundation. It exploits the very trust that holds communities together.

Combating it requires more than police reports. It demands active, engaged citizenship. It requires children to call their parents, neighbors to notice unfamiliar vans, and local newspapers to report on these crimes without sensationalism but with clarity. The goal is to shrink the space in which these criminals can operate.

As the population ages, the pool of potential targets grows. The methods will evolve, from fake cleaners to phishing calls and digital scams. The core defense, however, remains constant: connection, communication, and a collective refusal to let the most vulnerable members of society be isolated and preyed upon. The loss in Täby is measured in kronor, but the true cost is counted in broken trust. Can a high-trust society defend its principles without abandoning them?