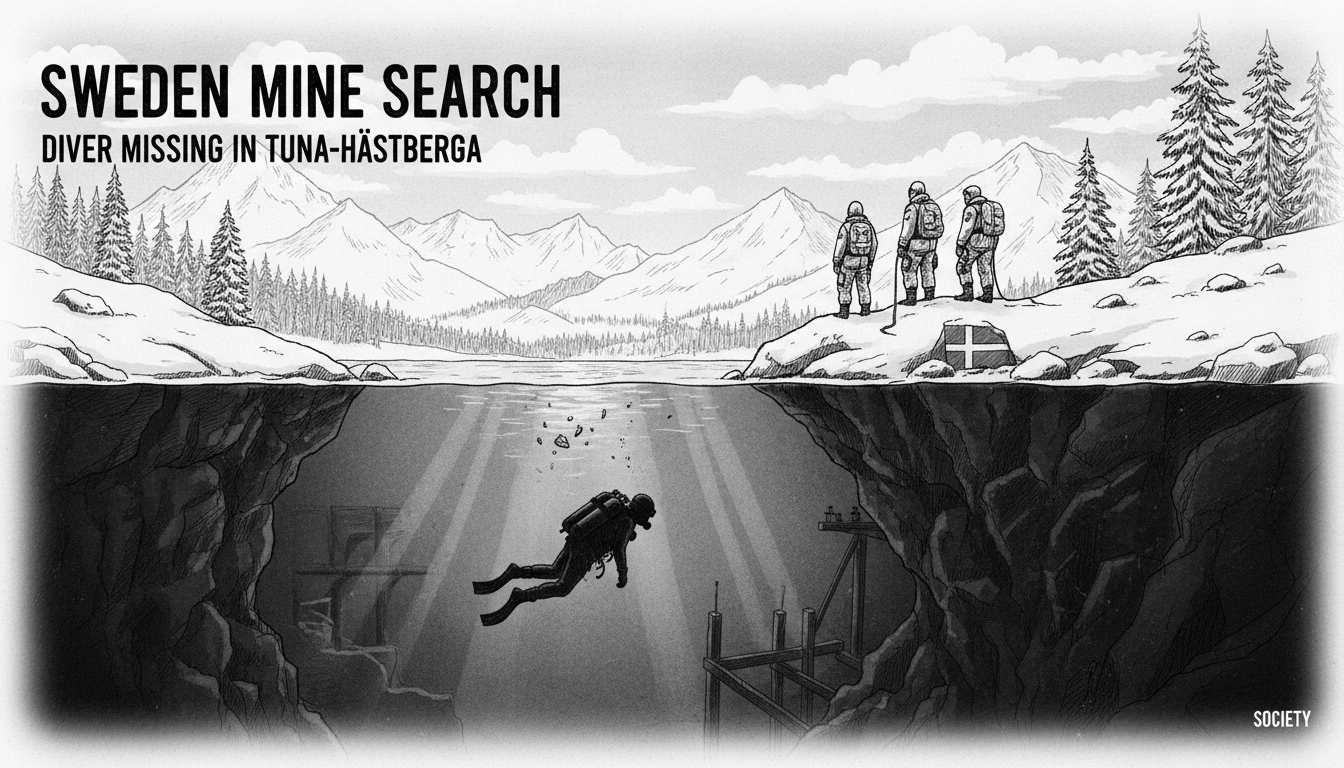

Swedish rescue teams are searching for a diver missing in the Äventyrsgruvan, or Adventure Mine, in Tuna-Hästberga near Borlänge. Police and emergency services are on the scene in a tense operation that highlights the risks of a niche adventure sport in a region built on mining history. The incident has cast a shadow over a facility that normally echoes with the laughter of tourists, not the urgent radio calls of rescue crews.

A Tense Scene in Dalarna

The operation is focused on a former iron ore mine, now a tourist attraction, in the quiet village of Tuna-Hästberga. The area is part of the historic Bergslagen region, the heartland of Sweden's mining industry for centuries. Today, the mine offers guided tours and adventure activities. The specific activity the missing diver was engaged in has not been officially confirmed, but the location points towards the high-risk pursuit of mine diving. This involves exploring flooded mine shafts and chambers, a discipline requiring expert training due to near-zero visibility, tight spaces, and unpredictable environments.

Local reports describe a significant emergency presence. The mood is one of focused urgency. "When the call comes for a missing diver in a mine, every second counts, but the operation cannot be rushed," says a veteran Swedish rescue coordinator familiar with such operations, who asked not to be named. "The environment is your enemy. Darkness, cold, unstable rock, and hidden obstacles turn a simple search into a complex puzzle."

The Allure and Peril of Mine Diving

Why would anyone dive in a flooded mine? For enthusiasts, it's the ultimate adventure, exploring a hidden, industrial underworld frozen in time. Sweden, with its abundance of abandoned mines, has become a destination for this small community. The water is often clear and cold, preserving machinery and tools left behind. But the beauty masks extreme danger. There is no natural light, no easy exit to the surface, and layouts can be confusing labyrinths of tunnels and shafts.

"It's not like open-water diving," explains Lars Pettersson, a Stockholm-based technical diving instructor. "Navigation is everything. You are completely reliant on your guideline back to the entrance. One lost line, one stirred-up cloud of silt, and you are disoriented in total blackness. The training is rigorous for a reason." The sport demands redundant breathing systems, specialized lights, and meticulous planning. Even with all precautions, the margin for error is vanishingly small.

From Iron Ore to Adventure Tourism

The Äventyrsgruvan's story reflects a broader trend in Sweden's post-industrial regions. As active mining consolidated into larger, modern operations, many smaller historical mines were abandoned. Communities have had to find new uses for these sites. Converting them into museums and adventure attractions provides both cultural preservation and tourism revenue. It's a way to keep the region's identity alive.

Walking through the dry parts of such a mine, you can feel the weight of history. You see drill marks from centuries past and imagine the lives of the miners who worked there. This deep connection to the land and its resources is a core part of Swedish culture, particularly in regions like Dalarna. The adventure tourism model seeks to make that history tangible, albeit with modern safety protocols for standard tours.

The Complex Reality of Mine Rescue

Search operations in a mine, especially a flooded one, are slow and methodical. Rescue divers themselves face the same lethal environment. They must carefully navigate, ensure their own safety, and systematically check side tunnels and chambers. The structure of an old mine can be unstable; disturbing the water or touching a wall could cause a collapse. Furthermore, water temperature, which is near freezing year-round in deep Swedish mines, leads to rapid heat loss and limits dive times.

There is also the psychological pressure on the rescue teams. They are navigating a space where someone is lost, working against a clock where survival time is uncertain. Swedish emergency services train for these scenarios, but each real incident presents unique challenges. The community waits, hoping for a team of specialists to succeed where the adventure turned tragic.

A Community Holds Its Breath

In towns like Borlänge and the surrounding villages, news of the incident travels fast. For locals, the mine is a landmark. Some may have relatives who worked there before it closed. Others may have taken their children on a summer tour. It is a part of the local fabric. An accident there feels personal, a stark reminder that the peaceful, forested landscape rests atop a man-made labyrinth with its own dangers.

This incident will inevitably spark conversations about risk, regulation, and the limits of adventure tourism. Sweden prides itself on a strong safety culture, from workplace regulations to public event planning. Activities like mine diving operate in a specialized niche, often governed by club rules and personal responsibility rather than broad legislation. The coming days will see authorities examining the circumstances of this dive in minute detail.

Looking Ahead: Questions After the Search

Regardless of the outcome of the ongoing search, this event leaves a mark. It raises difficult questions. How are high-risk adventure activities balanced with personal freedom in a safety-conscious society like Sweden's? What level of oversight is appropriate for activities undertaken by trained specialists? For the adventure tourism industry, it is a sobering moment that will lead to reviews of safety protocols and client qualifications.

For the public, it is a tragic story that merges Sweden's proud industrial heritage with modern pursuits of extreme experience. It highlights the silent, water-filled chambers that lie beneath the familiar pine forests and red cottages of Dalarna. The rescue teams continue their work, meter by meter, in the dark water, representing the very best of Sweden's collective response to crisis. The hope of a village, and a nation, is with them.