Swedish police suspect a major mixing facility for dangerous counterfeit alcohol is operating in Stockholm. The theory emerged after an 18-year-old man was arrested during a routine check in the city last autumn. He was carrying 3,700 kronor in cash, and nearby, officers found 28 bottles labeled "Magic Crystal Vodka." Laboratory tests revealed the contents were not just vodka. The liquid was diluted with isopropanol, a toxic substance commonly found in windshield washer fluid and technical cleaning products. This discovery has sparked a wider investigation into what authorities fear could be a centralized, organized operation poisoning the city's underground market.

"We see the same pattern in several ongoing cases, and it's spread across the entire county," said local police officer Ludvig Sonehag Bröms. His statement points to a systematic problem, not an isolated incident. The potential existence of a blending hub suggests a scale of production that could flood neighborhoods from Södermalm to Solna with hazardous spirits. For residents, the news is a chilling reminder that the quest for cheap alcohol carries deadly risks far beyond a bad hangover.

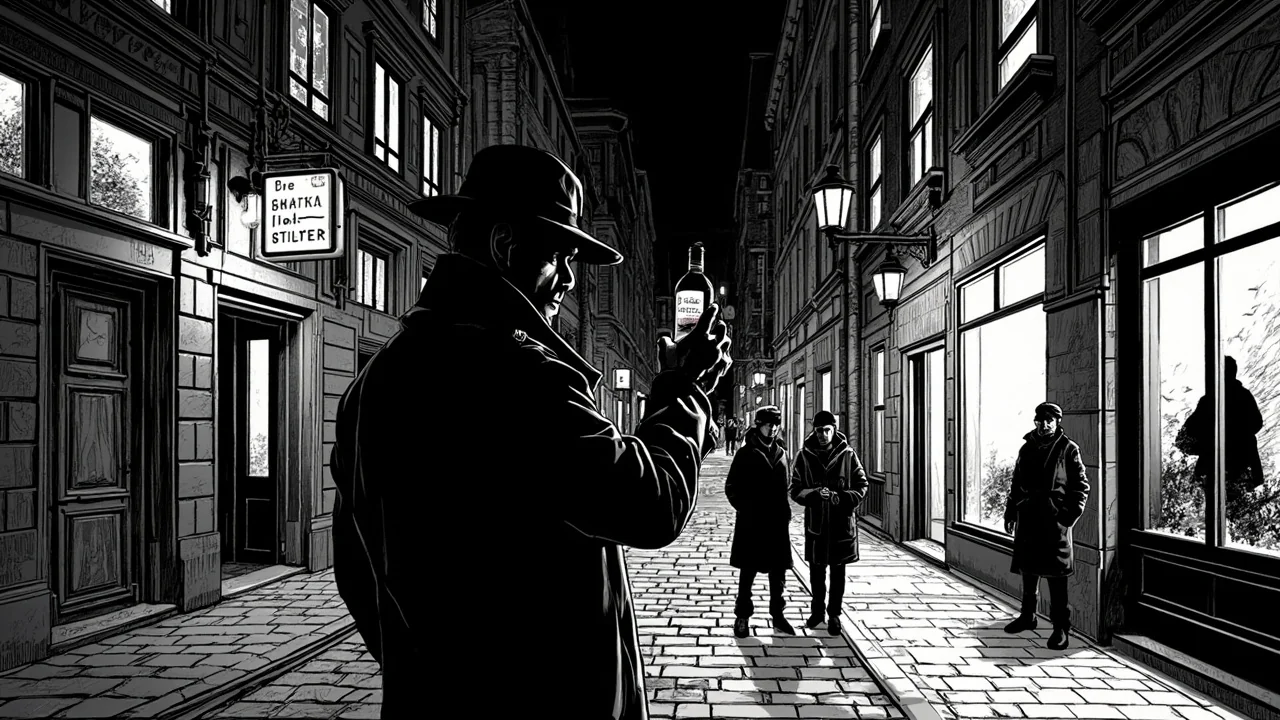

A Toxic Brew Hits the Streets

The arrest on that Stockholm parking lot was a critical break. Isopropanol poisoning is no minor issue. Consumption can lead to severe abdominal pain, dizziness, vomiting, and in the worst cases, organ failure, blindness, or death. The bottles, with their professional-looking "Magic Crystal" label, were designed to deceive. They target a specific demographic: young people, budget-conscious drinkers, and vulnerable individuals seeking alcohol at a fraction of the state monopoly Systembolaget's price. This isn't homemade moonshine in a rural shed; it's industrial-grade adulteration in an urban setting.

Stockholm's nightlife and private party scene provide a ready market. The high taxes on legitimate alcohol in Sweden create a persistent demand for cheaper alternatives. This economic reality fuels a black market that criminals are all too willing to exploit with lethal shortcuts. The police theory of a central mixing point indicates a move toward efficiency and scale in this illicit trade. Instead of small batches mixed in apartments, a single location could be supplying multiple distributors across the Stockholm region, creating a consistent and widespread public health threat.

The Human Cost of Counterfeit Culture

Behind the police theory are real people. I spoke with Mikael, a bartender at a popular club in Stureplan, who asked not to use his full name. "You hear whispers," he told me, wiping down the bar. "Kids coming in pre-drunk on something that smells... off. Not like alcohol, but chemical. They talk about buying bottles from a guy in a car for half the price. It's terrifying. We check IDs, but we can't control what they drink before they get here." His concern is shared by social workers in suburbs like Rinkeby and Tensta, where community leaders have long warned about unregulated substances circulating alongside drugs.

This story touches a nerve in Swedish society, which maintains a complex, state-controlled relationship with alcohol. The Systembolaget model is built on safety, quality, and controlled consumption. This illicit operation spits on that entire philosophy. It replaces safety with profit, quality with poison, and control with chaos. For immigrants from cultures with less regulated alcohol markets, the danger is particularly acute. They may be unfamiliar with the Swedish system and more trusting of a bottle that looks legitimate, sold by someone who speaks their language.

Following the Money and the Chemistry

The 3,700 kronor in cash found on the arrested teen is a key clue. It suggests an active sales operation, with runners being paid to distribute the product. Police are likely following financial trails and communication patterns to map the network. The use of isopropanol is also significant. It's a cheap, readily available industrial solvent. Its inclusion isn't a mistake; it's a calculated way to increase volume and potency cheaply, with little regard for the consumer. The choice of chemical reveals a cold, business-minded approach to the trade.

Experts in organized crime see this as part of a diversification trend. "When police pressure increases on drug trafficking or explosives, criminal networks look for other high-profit, lower-risk ventures," explains a security analyst I consulted. "Counterfeit alcohol is one. The raw materials are cheap and easy to get, the production isn't overly complex, and the market is guaranteed. The penalties, historically, have not been as severe as for narcotics. That may need to change." This analyst believes the central mixing facility theory is plausible, as it mirrors the logistics models used in other illicit trades.

A Societal Challenge Beyond Policing

While police work to dismantle the suspected operation, the problem demands a broader response. Public health authorities must amplify warnings in multiple languages, targeting communities through social media and local clinics. Schools and youth centers in Stockholm need to have frank discussions about the risks, moving beyond standard alcohol education to address this specific, poisoned threat. The municipality's party scene organizers could play a role in spreading awareness.

The incident also reignites the perennial debate about Sweden's alcohol policy. Some argue the high prices and restricted access at Systembolaget directly create the black market that this fake ring supplies. Others contend that the state monopoly ensures quality and safety, and the solution is stricter enforcement and harsher penalties for those who circumvent it. This fake vodka operation is a grim test case for which argument holds more weight in protecting citizens.

What Comes Next for Stockholm?

The search for the mixing facility continues. Police are cross-referencing data from seizures, traffic stops, and financial reports. Every bottle of "Magic Crystal" or similar counterfeit brand taken off the street is a potential clue to its origin. The question hanging over Stockholm is not just if this central hub exists, but where. Is it in a warehouse in an industrial park in Värtahamnen? A locked garage in a suburban apartment complex? The anonymity of the city provides both cover and customers.

For now, the warning is clear. That bargain bottle of vodka from an unknown seller isn't just illegal; it's potentially lethal. The promise of cheap fun could end in an ambulance ride to Karolinska University Hospital. As police pursue their theory, the city is left to grapple with a sobering reality: in the shadows of its vibrant culture, a business is mixing poison for profit. The true cost will be measured not in kronor, but in human health. How many more Magic Crystal bottles are still out there, waiting to be opened?