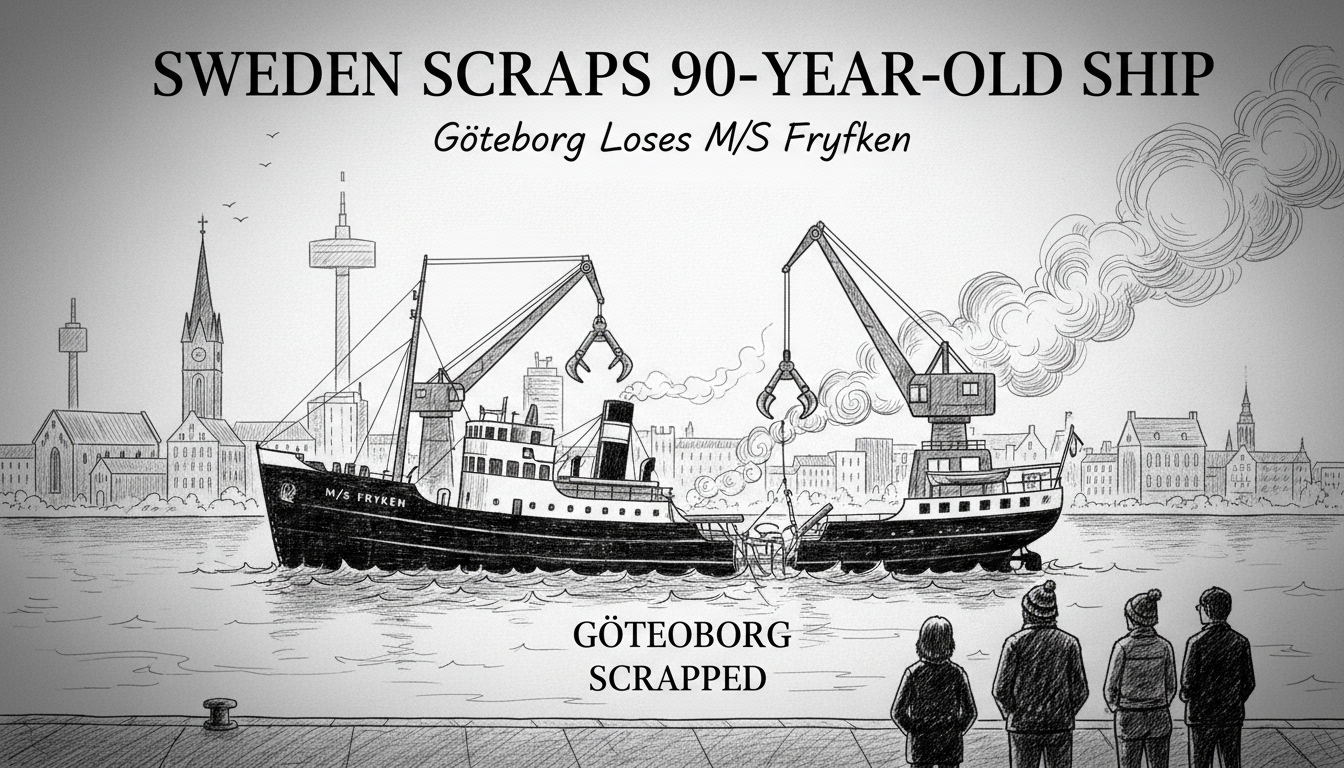

Sweden's Göteborg lost a 90-year-old piece of maritime history last Saturday night. The storied vessel M/S Fryken made its final, unlit trip down the Göta Älv river, heading to be scrapped after years of service and recent neglect. Simon Fredrin, captain of the sightseeing boat M/S Trubaduren, captured the somber moment from the water. 'It looked a bit depressing when it was completely dark,' he said, describing the scene near the Eriksberg district. For 40 years, the ship had been part of the city's landscape. A lack of a paying tenant and a permanent berth forced the owner, the Maritiman maritime museum, to send it for scrap.

From Atlantic Crossings to Classroom

The ship's history reflects a bygone era of Swedish trade. Built in the 1930s, the M/S Fryken originally worked liner traffic. It sailed between Lake Vänern, Gothenburg, and the east coast of Great Britain. After its commercial life ended, it found new purpose. For decades, it was a static exhibit at Maritiman, floating beside other historic vessels in the city's harbor. Its most recent chapter began in 2016 when Maritiman loaned it to the prestigious Chalmers University of Technology. Students training to become ship captains and marine engineers used it as a hands-on training vessel. 'I actually had my internship there when I studied at Chalmers to become a sea captain in 2021, so I've been on board,' Captain Fredrin shared, connecting his own education to the ship's fate.

The Silent Farewell on Göta Älv

The end came quietly after years of inactivity. Maritiman had not displayed the ship publicly for some time. With no revenue from charters or a museum berth, the costs of maintaining a 90-year-old steel hull became impossible to justify. Around 10:30 PM last Saturday, tugboats moved the dormant vessel from its mooring at Eriksberg. It began its final voyage down the river, past the bustling port and under the city's bridges, bound for the scrapyard. This stretch of water, the Göta Älv, is the same route it would have taken loaded with cargo for England nearly a century ago. The contrast between its lively past and its dark, silent departure was not lost on local maritime enthusiasts watching from shore.

A Broader Crisis for Floating History

The scrapping of M/S Fryken is not an isolated event. It highlights a severe challenge facing maritime preservation across Sweden and the Nordic region. 'Every ship like this tells a specific story about our engineering, trade, and social history,' explains maritime historian Jens Olsson, who consulted on several preservation projects. 'But they are incredibly expensive to maintain. The hull requires constant anti-corrosion care. Docking space in popular city centers is scarce and valuable. Without a clear, funded purpose—as a museum, restaurant, or training ship—they become liabilities.' Olsson points to similar fates for other vessels in Stockholm and Malmö. The economic model for preserving large historical ships is cracking. Public funding is limited, and corporate sponsorship often seeks more visible projects.

What Gets Saved, and Why?

This incident forces a difficult conversation about cultural heritage. Which artifacts are essential to save? A historic ship is not like a painting in a climate-controlled gallery. It is a giant, dynamic object exposed to wind, saltwater, and time. The decision often comes down to a unique historical significance or a strong, active community group to champion it. M/S Fryken, while old and with an interesting past, may have fallen into a gray area. It was not the first of its kind, nor the last. Its association with Chalmers gave it a modern purpose, but that ended. 'We are forced to make tough prioritizations,' a Maritiman representative said in a statement. 'Our resources must focus on the core fleet we can maintain and exhibit properly for the public.'

The Personal Connection to the Past

For those who worked or studied on the Fryken, its loss is personal. It was a tangible link to the maritime world they were entering. The feel of its deck plates, the layout of its engine room, and its very presence provided context that textbooks cannot. This erasure of physical history creates a gap. Future Chalmers students will learn on modern simulators or other vessels, but the direct connection to 1930s maritime engineering is now severed. Captain Fredrin's footage may become one of the primary records of the ship's final moments. This shift from physical preservation to digital archival is becoming more common. Museums photograph, scan, and document ships in detail before they are dismantled, saving the data if not the object.

Looking Ahead in Göteborg's Port

Gothenburg's identity is deeply tied to the sea. The city's maritime cluster is a major economic driver. Preserving the physical evidence of that history is a constant struggle against economics. The M/S Fryken's departure leaves an empty space on the water, a subtle change in the city's silhouette. Its story—from transatlantic trader to classroom to scrap—mirrors the lifecycle of many industrial artifacts. The event prompts a question for all Swedes who value their history: As the last ships from the early 20th century age, what are we willing to invest to keep them afloat? The silence of the Fryken's final trip down the Göta Älv might be the loudest warning yet.