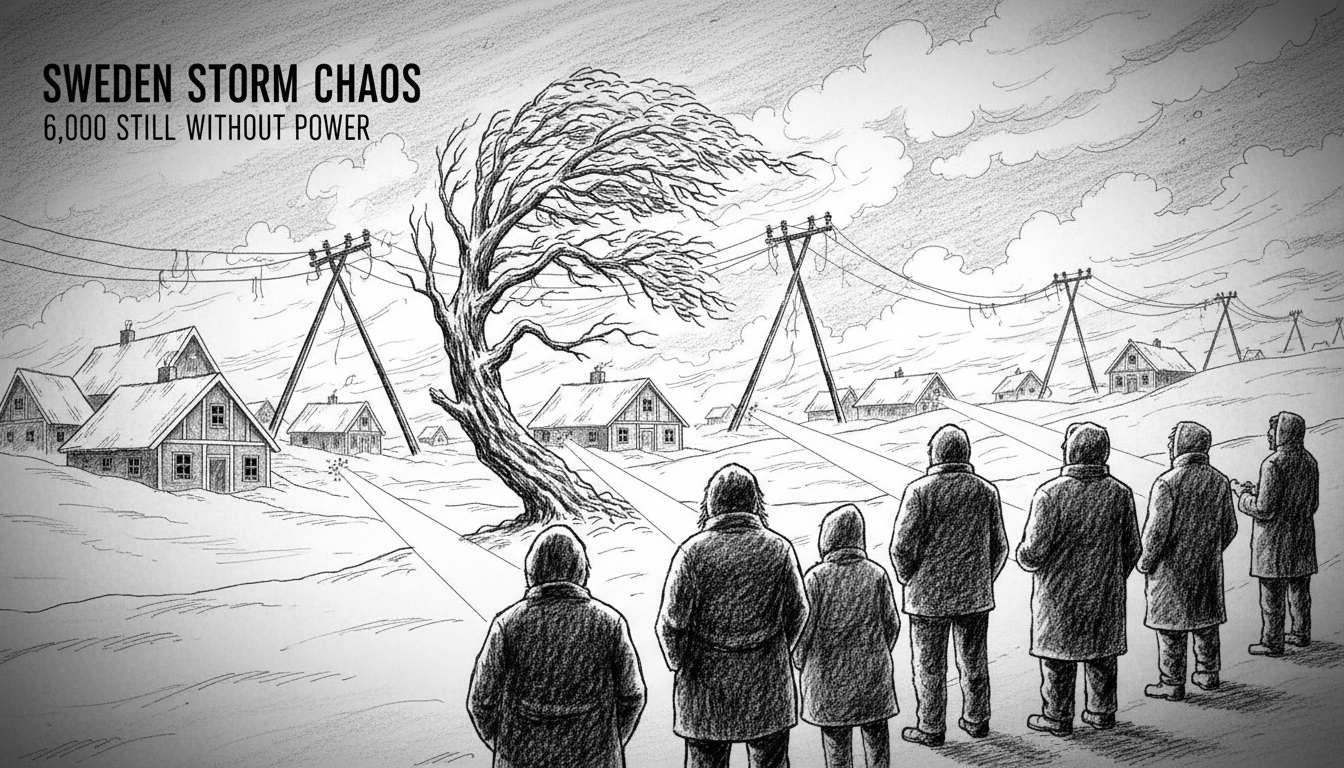

Sweden's Storm Johannes has left thousands facing a cold and dark New Year. The severe weather, which swept across northern and central Sweden, initially cut power to 40,000 households and claimed three lives. As of late Tuesday afternoon, around 6,000 customers in the worst-hit region of Gävleborg County remained without electricity. Now, a fresh orange weather warning for heavy snowfall threatens to further delay restoration efforts, prolonging the misery for those already struggling.

For families like the Erikssons in rural Hälsingland, the storm has turned the holiday season into a test of endurance. "We lost power on Saturday afternoon," says Karin Eriksson, speaking from a relative's home where her family has sought refuge. "The house is getting colder by the hour. We have a wood stove, so we can manage some heat, but no light, no running water, and our freezer is thawing. We just want to go home." Her story echoes across the forested communities of southern Norrland, where the crunch of boots on frozen ground and the hum of private generators have replaced the usual quiet.

A Race Against Time and Weather

The timing of the new snowfall is particularly cruel, according to power companies scrambling to repair the grid. "It's very poor timing for this snowfall," says Jonatan Björck, a press officer for the network company Ellevio. His team and those from Eon and Vattenfall have been working around the clock since Storm Johannes hit on Saturday. The storm, described by the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) as the most severe this year, brought record-strong winds that toppled trees and power lines across a vast area.

Restoration work is a monumental task. Crews must first locate the often remote faults, clear fallen timber and debris, and then repair or replace damaged lines and pylons. The fresh snow warning, active from New Year's Day lunchtime until Friday morning, complicates everything. It forecasts 20 to 40 centimeters of snow combined with wind in southern Norrland's coastal areas. This will make roads impassable, obscure damage sites, and create hazardous working conditions for repair teams. "Every new centimeter of snow sets us back," Björck explains. "Safety for our crews is paramount, which means work may have to pause if conditions become too dangerous."

The Human Cost of a Dark Winter

The impact extends far beyond a simple inconvenience. In Sweden's winter, a power outage is a serious threat to basic welfare. Without electricity, heating systems fail, water pipes risk freezing and bursting, and food spoils. For the elderly and those with medical needs reliant on powered equipment, the situation is critical. Municipalities in Gävleborg have opened emergency warming shelters in community centers and schools, providing hot meals, charging stations, and a place to sleep.

In the small coastal town of Söderhamn, local baker Magnus Lindgren has kept his ovens fired up using a backup generator. "We've been giving away bread and letting people come in to warm up," he says. "It's what you do. This storm has shown us how fragile the normal life is. One day you have everything, the next you are boiling snow for water." This community response, a concept deeply rooted in the Swedish ideal of 'gemenskap' (togetherness), has been a bright spot in the crisis. Neighbors are checking on each other, and those with wood-fired saunas are offering them as warm sanctuaries.

Infrastructure at the Mercy of the Climate

This event throws a harsh light on the vulnerability of Sweden's energy infrastructure, particularly in its vast, forested north. While Sweden's energy production is robust—relying on hydroelectric, nuclear, and a growing share of renewables—its distribution network in rural areas is exposed. Power lines often run through dense forests, making them susceptible to falling trees during storms. Professor Elin Söderberg, an energy systems researcher at Uppsala University, notes this is a growing challenge. "We are building a more renewable energy system, but the grid remains a physical network vulnerable to extreme weather," she says. "Events like Storm Johannes are consistent with climate models that predict more frequent and intense winter storms in Scandinavia."

Experts point to two key solutions: hardening the existing grid and diversifying local energy sources. Hardening can include burying power lines, a vastly expensive but more resilient option, or creating wider clearances around overhead lines. Diversification means encouraging more households and communities to install local solar with battery storage or small-scale wind, creating micro-grids that can operate independently if the main grid fails. "The debate is about cost versus resilience," Söderberg adds. "Who pays for reinforcing a grid that serves sparse populations? But the human and economic cost of these prolonged outages is also immense."

A Long Road to Recovery

As New Year's Eve approaches, the mood in many homes is somber rather than celebratory. The traditional Swedish New Year's feast of steak and lobster, or a quiet night watching the annual 'Kalle Anka' (Donald Duck) television special, is cancelled for those still in the dark. For the power companies, the goal is to restore as many connections as possible before the new snow hits. However, they warn that some isolated properties may face days more without power.

The storm's legacy will be felt long after the lights come back on. Insurance claims will flood in for spoiled food and potential pipe damage. Local businesses have lost crucial holiday revenue. And for Swedish authorities, Storm Johannes serves as a stark case study. It highlights the urgent need to future-proof essential services against a changing climate. The question is no longer if such an event will repeat, but when. As the people of Gävleborg County huddle for warmth, Sweden must decide how to build a society that can weather the storms to come.