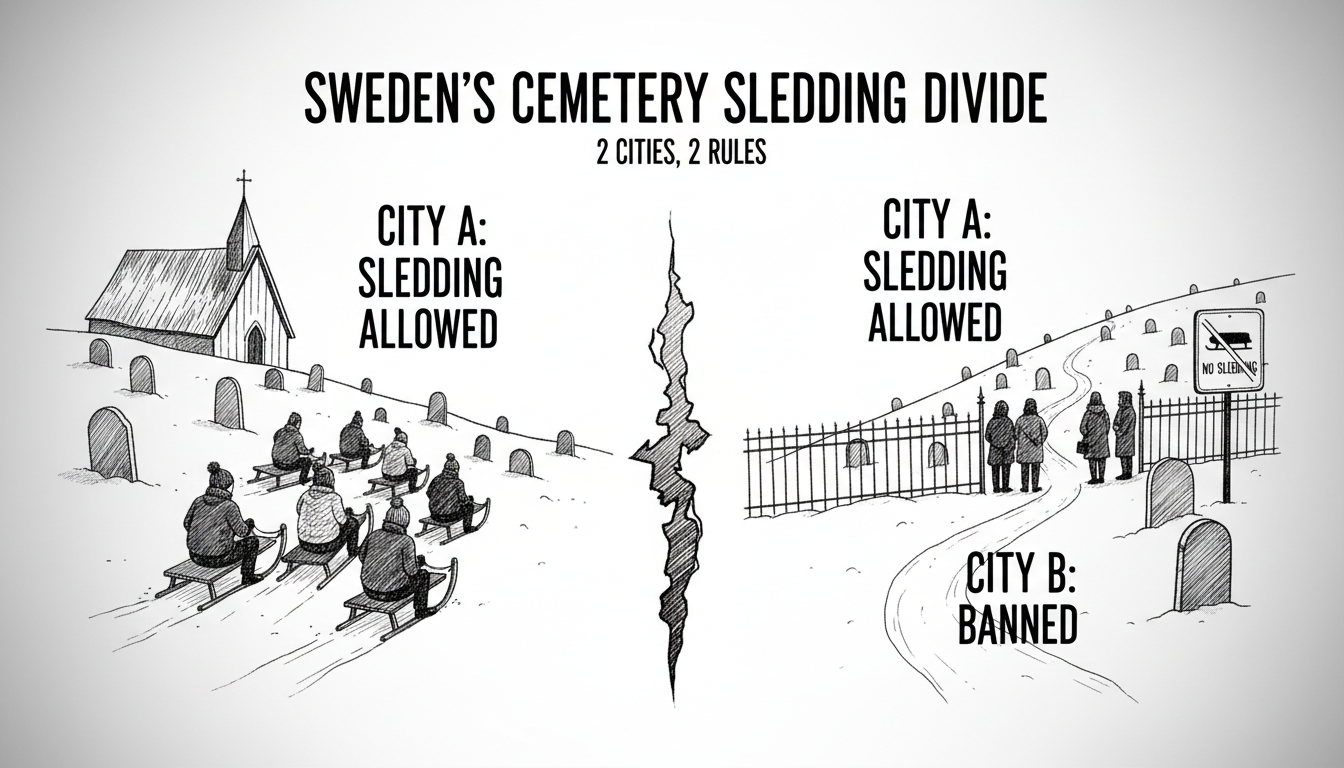

Sweden's approach to cemetery use reveals a stark policy divide between its two largest cities. While Stockholm officials actively discourage the practice, Gothenburg’s burial authorities adopt a more permissive, case-by-case stance. This contrast highlights evolving Nordic attitudes towards public space, tradition, and community life in sacred areas.

Erik Gedeck, head of administration for the Gothenburg Burial Association (Göteborgs begravningssamfällighet), articulated this flexible position. "If it's done with consideration in a well-chosen place so that visitors are not disturbed, I don't rule out that it could be a possibility," Gedeck stated. His comments reflect a pragmatic governance style focused on local context and respectful coexistence.

A Capital Contrast

In Stockholm, the narrative differs significantly. Authorities at the city's largest cemetery, Skogskyrkogården, have issued public appeals in recent winters. They ask families to refrain from using the grounds for sledding, known in Swedish as "pulkning." This request emphasizes maintaining a solemn atmosphere for mourners and respecting the primary function of the burial ground. The capital's approach prioritizes undisturbed reverence, setting a clear boundary for recreational activity.

Gothenburg's policy does not establish a universal ban. Instead, it places trust in public judgment and parental guidance. The association manages multiple cemeteries across the city, requiring nuanced oversight. Gedeck's statement implies that quiet, selective use of certain slopes may be tolerated if conducted discreetly. This creates an unofficial social contract between the management and the city's residents.

Historical Spaces, Modern Uses

Churchyards in Sweden have historically served as central community spaces beyond their funerary purpose. For centuries, they were gathering points, marketplaces, and even grazing grounds. The current debate continues this long tradition of negotiating a cemetery's role. It questions whether these spaces can simultaneously honor the dead and accommodate the living community's seasonal rhythms.

The Church of Sweden, which manages many cemeteries nationwide, faces a complex balancing act. Its mission includes pastoral care for the bereaved and stewardship of consecrated land. It also involves engaging with the wider community, including families who may not be regular congregants. A blanket prohibition on all non-funerary activities can seem detached from contemporary urban life where green space is limited.

Expert Analysis: The Living Cemetery

Cultural geographers note this is part of a broader European conversation. "Cemeteries are increasingly viewed as multifunctional green spaces in dense cities," explains Dr. Lena Möller, a sociologist specializing in public space at Uppsala University. "The key is managing different types of visitation—mourners seeking solitude, tourists on historical walks, and locals enjoying nature—without letting one group exclude others."

Dr. Möller suggests that clear, compassionate communication is vital. "Signage indicating 'Quiet Zones' or 'Respectful Play Allowed Here' can be more effective than total bans," she says. This zoning approach acknowledges that a vast cemetery has areas of varying character and use intensity. A child's laughter near a main path might be less intrusive than sledding over older, less-visited plots.

Ethicists point to the core question of respect. "Respect for the deceased and their families is non-negotiable," states Professor Arvid Jensen, who teaches applied ethics. "But respect can be shown in different ways. A quiet, joyful family activity conducted mindfully may not inherently disrespect the dead. In fact, it could be seen as celebrating life within a cycle of memory."

Implications for Municipal Policy

The divergent approaches between Stockholm and Gothenburg show how local culture influences policy. Stockholm, as the national capital and a larger metropolitan area, may experience higher visitor numbers and feel a greater need for formal rules. Gothenburg's stance reflects a perhaps more informal West Coast attitude, relying on societal norms, known as "folkvett."

This issue touches on deeper themes of Swedish societal trust. The permissive model operates on the assumption that citizens will self-regulate and exercise good judgment. The restrictive model assumes clear rules are necessary to prevent disturbances. Both systems aim for the same outcome: peaceful, respectful cemetery grounds. Their methods, however, are philosophically distinct.

For other Swedish municipalities and cemetery boards, this creates a reference point. They can observe the outcomes and public reception in both major cities. The debate may influence future guidelines from the national Church of Sweden, as it seeks a coherent yet adaptable framework for its hundreds of churchyards.

The Path Forward

Gedeck's qualified openness in Gothenburg suggests a potential middle path. It acknowledges winter's reality in Sweden, where snow-covered hills are a magnet for children. It also recognizes that cemeteries, often on picturesque land, are inherently attractive for such activities. The policy implicitly asks: Is it better to have a tolerated, supervised activity or to drive it underground without any oversight?

Practical considerations include safety and maintenance. Cemetery paths must be clear for maintenance vehicles and visitors, especially the elderly. Sledding must avoid damaging graves, headstones, or plantings. These practical concerns form the basis of Gedeck's condition that any activity must occur in a "well-chosen place."

As Swedish cities continue to grow and green space becomes ever more precious, the function of all public land is scrutinized. Cemeteries represent a significant portion of tranquil, cultivated green areas in urban environments. Their management requires wisdom to honor their sacred purpose while acknowledging their place in the community's ecosystem.

The final question remains for society: Can spaces for the dead also nurture the living, and where should the line be drawn? Sweden's two largest cities are currently drawing that line in different places, providing a real-time case study for the rest of the nation and beyond.

Word count: 864