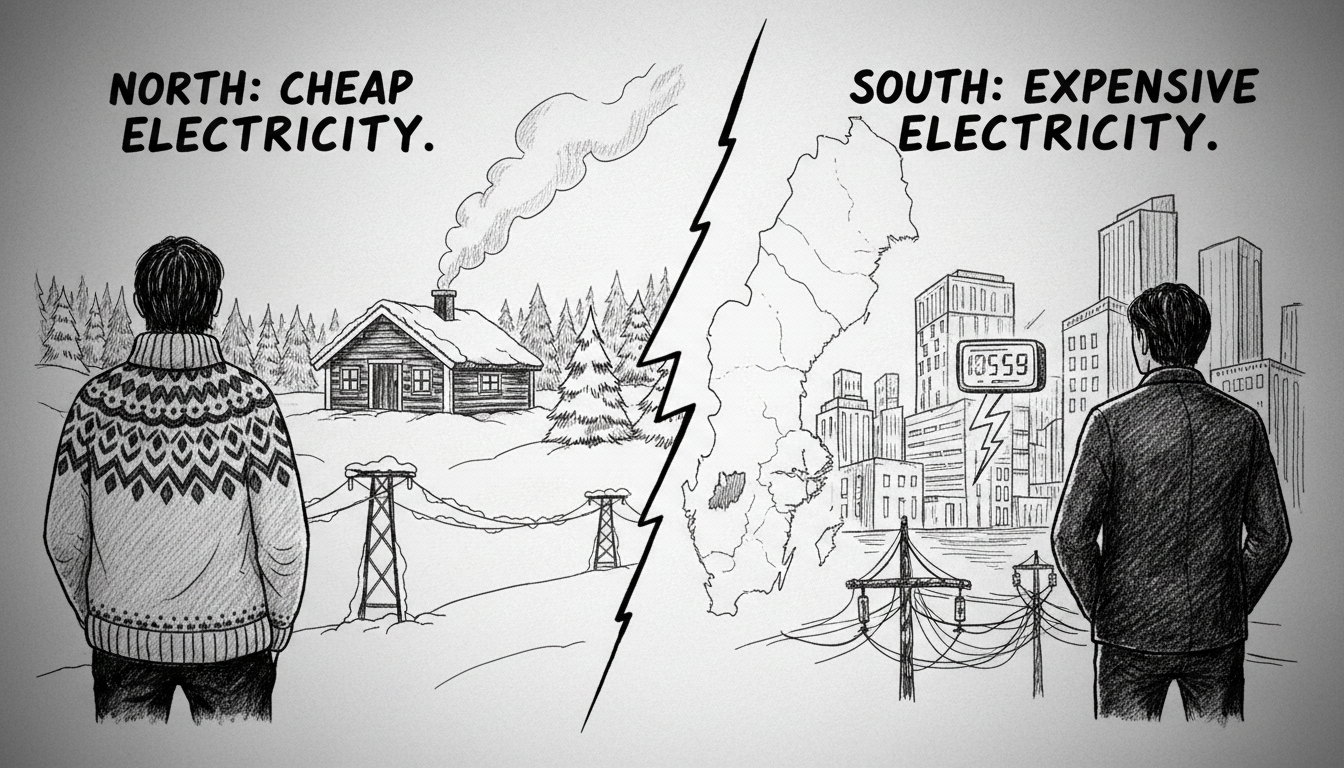

Sweden's electricity market is splitting in two. This summer, consumers in the north enjoyed near-record low power prices. Meanwhile, bills in the country’s southern regions remained stubbornly high. This growing price gap highlights a critical bottleneck in the nation’s energy infrastructure that could slow its ambitious climate goals.

A Nation Divided by Price Zones

Sweden operates four electricity price zones. SE1 (Luleå) and SE2 (Sundsvall) cover the north. SE3 (Stockholm) and SE4 (Malmö) cover the central and southern regions. Prices are set on the Nord Pool power exchange. They fluctuate based on local supply and demand. When transmission lines between zones are full, prices can diverge dramatically.

This June, the divide was extreme. Northern zones saw some of the lowest prices in years. Southern zones paid significantly more. "Limited transmission capacity from north to south means power is locked in northern Sweden. This created near-record low prices during June," said Magnus Thorstensson, an analyst at the industry group Energiföretagen, in a published commentary. This analysis points to a structural flaw, not a temporary glitch.

The Hydropower Advantage and the Grid Bottleneck

The root cause lies in geography and infrastructure. Northern Sweden's power mix is dominated by hydroelectric dams. This summer, heavy rainfall filled reservoirs to high levels. Hydro plants generated abundant, low-cost electricity. This bounty should benefit the whole country. Sweden’s grid, however, lacks the capacity to move large volumes southward.

Think of the national grid as a highway system. The roads from the north to the populous south have too few lanes. When northern hydro production is high, traffic jams form on these power lines. The cheap electricity cannot get through. Southern Sweden must then rely on more expensive sources. These include power imports from the continent and domestic gas-peaking plants.

The Surprising Trend of Falling Consumption

Amidst this regional price drama, a broader national trend continues. Sweden's total electricity consumption is falling. Preliminary data from 2023 suggests a continuing decline. This appears counterintuitive. National discourse focuses on the massive electrification of transport and industry. Yet, improved efficiency in homes and businesses is having a measurable impact.

High prices in the south have also forced conservation. Industries are optimizing consumption. Households are more conscious of usage. This demand reduction provides temporary relief for the strained system. It does not, however, solve the fundamental transmission problem. Long-term forecasts still project soaring demand as fossil fuels are phased out.

A Market Under Multiple Pressures

The Nordic electricity market is feeling global pressures. While hydropower conditions are local, other factors are international. The price of natural gas in Europe influences costs in southern Sweden. Wind power generation in Denmark and Germany affects import and export flows. These interconnected forces complicate Sweden's domestic price puzzle.

Nuclear power remains a key pillar. It provides stable baseload power, primarily from plants in the south. This helps moderate prices in SE3 and SE4. The retirement of older reactors in recent years has increased southern Sweden's reliance on imports and variable sources. This has made price spikes more likely during calm, cold periods when wind generation is low.

The Investment Imperative: Wires Before Megawatts

Analysts are unanimous on the primary solution. Sweden must invest heavily in its national grid. Building new power lines and upgrading existing ones is a multi-billion euro challenge. The process is slow. It faces regulatory hurdles and local opposition. New transmission projects can take over a decade to plan and build.

“The discussion often focuses on building more generation—more wind, more solar, more nuclear,” said an energy economist who requested anonymity to speak freely. “But right now, the most critical need is to build more wires. We have cheap, green power in the north. We need it in the south. The business case for grid expansion is overwhelming.”

This creates a political dilemma. The benefits of a stronger grid are national. The burdens of new power lines are local. Communities often resist having major transmission corridors built through their landscapes. Sweden's permitting process must balance these competing interests while recognizing the urgency.

What This Means for Businesses and Households

The price divide has real economic consequences. A data center company or a green steel startup looking to build a facility faces a major choice. Locating in the north offers drastically lower, more stable electricity costs. This incentivizes investment and job creation in less populated areas. It could exacerbate regional economic disparities.

For a family in Stockholm or Malmö, the issue is one of monthly budgeting. Higher electricity costs strain household finances. They also make electric vehicles and heat pumps less economically attractive. This risks slowing the very transition Sweden is trying to accelerate. The social contract of the energy transition—that green power will be affordable—is under stress in the south.

The Swedish government and grid operator Svenska Kraftnät are aware of the crisis. Major grid expansion projects are in various planning stages. Their completion, however, is years away. In the interim, the market will continue to signal this deep imbalance through the price mechanism. The danger is that high southern prices could trigger a political backlash against climate policies themselves.

Sweden presents itself as a green energy leader. Its abundant hydropower and high nuclear share give it a decarbonization advantage few countries possess. Yet, its internal grid constraints tell a different story. Can a nation celebrated for its engineering prowess fix its own energy arteries before the pressure builds too high? The answer will determine not just power prices, but the pace of Sweden's entire fossil-free future.