Gothenburg's Järntorget square has transformed from a tired transit zone into a vibrant public living room. The newly inaugurated Olof Palmes plats, a dedicated section of the historic square, now features sofas, small stages, and magnolia trees. This urban renewal project aims to reclaim space for people, not just vehicles, in Sweden's second-largest city.

"The hope is that people will choose to come here during their lunch break to eat their packed lunch," said project leader Marit Sternang during Saturday's opening. Her simple wish captures the core ambition of the redesign: to create a place for spontaneous daily life. For decades, Järntorget served primarily as a hectic bus and tram interchange. Its worn asphalt was a surface to cross quickly, not a destination. The renovation, part of a broader city center development plan, seeks to change that fundamental relationship between citizens and their urban environment.

From Transit Hub to Community Heart

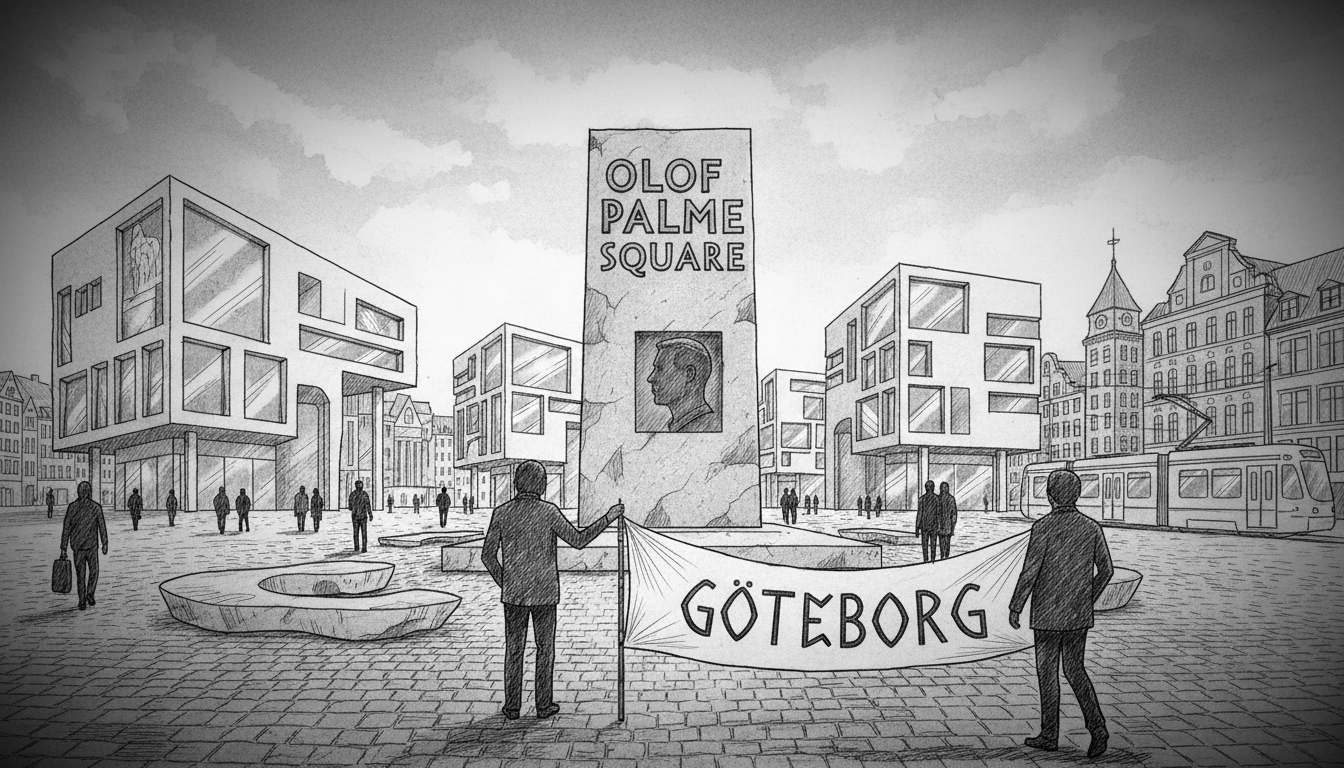

The shift at Järntorget reflects a global trend in urban planning, but with a distinctly Swedish social democratic flavor. By naming the renewed space after Olof Palme, the city connects physical change to political legacy. Palme, Sweden's Prime Minister assassinated in 1986, was a towering figure known for his advocacy of the public sphere and international solidarity. Naming a new gathering place after him is deeply symbolic. It suggests a plaza meant for dialogue, democracy, and community—ideals he championed. This isn't just a cosmetic upgrade; it's a statement about the kind of city Gothenburg wants to be.

Urban design experts see such projects as critical social infrastructure. "Well-designed public spaces are the glue of a city," explains Lars Forsberg, a professor of urban sociology at the University of Gothenburg, who is not directly involved in the project. "They provide a neutral ground for interaction across social, economic, and cultural lines. When you replace a traffic-dominated area with seating and greenery, you're investing in social capital and public health. You're saying that the right to the city belongs to everyone, not just those in cars."

The Design of Daily Life

Walking through the new Olof Palme Square reveals a carefully considered design. The sofas are arranged in small clusters, encouraging conversation. The stages, though small, are positioned to host impromptu music or speeches. The magnolia trees, chosen for their spring blossoms, add a soft, natural element to the granite and brick. It’s a design that encourages lingering. On a recent afternoon, a group of office workers shared coffee on one sofa, while tourists consulted a map on another. A teenager sat alone on a bench, phone in hand, soaking up the sun. This mundane activity is precisely the point.

The location is key. Järntorget sits at the edge of the historic Haga district, with its cobblestone streets and wooden houses, and the modern main avenues of the city center. It's a natural meeting point. The redesign aims to leverage this inherent foot traffic, turning a pass-through zone into a pause point. For local businesses, this could mean increased visibility and customers who are now encouraged to stay, rather than rush to their next connection.

A Memorial in Motion

The choice to honor Olof Palme with a living, functional square, rather than a static statue, feels intentional. Palme's assassination on a Stockholm street in 1986 left an open wound in the Swedish psyche. The crime remains unsolved, a source of enduring mystery and pain. A traditional monument might focus solely on that tragedy. A bustling square, however, celebrates the ongoing vitality of the public life he valued. It becomes a memorial in motion, animated by the voices and activities of today's citizens.

"It feels right that it's a place for people," said Erik, a local historian who visited the square on its opening day. "Palme was a man of the people, often controversial, always engaged. A quiet, solemn corner wouldn't suit him. But a place where arguments might happen, where friends meet, where someone might give a speech—that feels more authentic." This perspective highlights how urban space can embody memory in active, rather than passive, ways.

The Challenge of Inclusive Space

Creating a successful public square involves more than installing furniture. The real test for the new Olof Palmes plats will be its inclusivity. Urban planners often speak of the "eyes on the street" concept for safety, but true inclusivity means welcoming all demographics at all hours. Will teenagers feel ownership of the space after school? Will elderly residents find it accessible and comfortable? Will it host cultural events that reflect Gothenburg's diverse population?

Gothenburg, like many Swedish cities, grapples with questions of integration and social tension. Public spaces can either bridge or reinforce divides. The design, with its open layout and multiple seating options, seems geared toward flexibility. The small stages could host everything from poetry readings in Arabic to jazz concerts or political debates. The management and programming of the space by the city will be as important as its physical design. It must be perceived as a truly public good, not a curated zone for a specific crowd.

A Model for Swedish Urban Renewal

The Järntorget transformation offers a potential model for other Swedish cities facing similar challenges. Many town centers struggle with the dual pressures of increased traffic and the need for more attractive, pedestrian-friendly zones. This project shows a commitment to prioritizing human experience over vehicular convenience. It also demonstrates a shift from grand, monumental planning to smaller-scale, tactical urbanism that improves daily life.

The investment in quality materials—durable stone, solid wood for the sofas—signals an intention for longevity. In Sweden's climate, a public space must withstand harsh winters and celebrate fleeting summers. The magnolia trees, which will bloom spectacularly each May, provide a seasonal marker and a connection to nature in the heart of the city.

As the afternoon light fades over the new sofas and the first leaves on the magnolias, the success of Olof Palmes plats will be written in the daily habits of Gothenburg's residents. Will the square become the preferred lunch spot Marit Sternang envisioned? Will it foster unexpected conversations and community events? The transformation of the worn asphalt is complete. Now, the more complex transformation—that of urban habit and social life—begins. The square stands as a quiet invitation, a question posed in granite and greenery: how will we use this space we've been given?