Sweden's second city, Göteborg, is facing a silent winter threat. The local rescue service has issued a stark warning about dangerous icicles and heavy snow masses building up on rooftops. Unusually heavy snowfall followed by freezing temperatures has created perfect conditions for these icy hazards. 'We have urged both the public to be alert and look out, but also property owners to check their roofs and remove icicles if there is a risk they could fall and injure someone,' says Lars Magnusson, regional operations manager for the Greater Göteborg rescue service. His warning cuts through the picturesque winter scene, reminding residents that Swedish winter carries real risks beyond the cold.

This annual battle against falling ice is a quintessential part of Swedish urban life. It blends practical safety concerns with a deeper cultural relationship to winter. For newcomers, the sight of cordoned-off sidewalks under glittering icicles can be surprising. For locals, it's a familiar seasonal ritual. The rescue service's alert is not just bureaucratic procedure. It is a necessary intervention in a city where pedestrian life continues briskly, even in deep winter. People walk to work, school, and the local 'systembolaget' regardless of the weather. This creates a unique urban challenge where architecture meets climate.

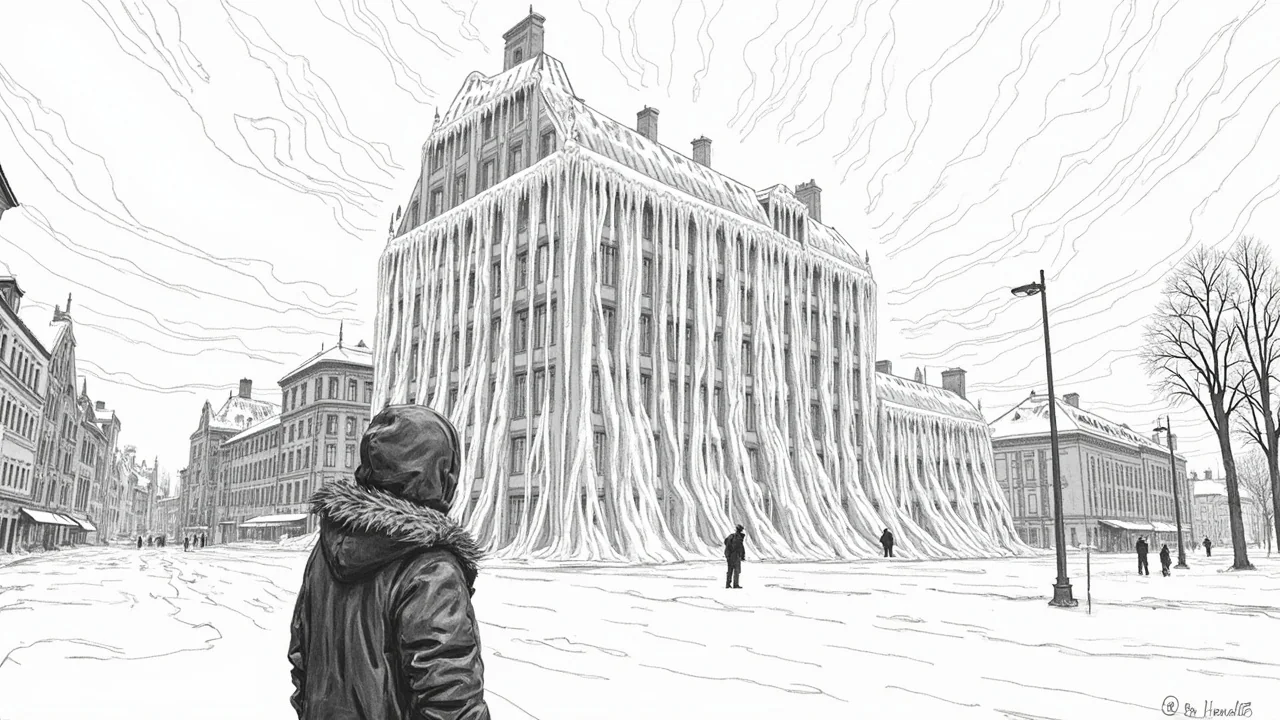

The Silent Hazard Above

The danger is deceptively beautiful. Long, spear-like icicles form along eaves and gutters. They catch the low winter sun, creating a sparkling effect. Meanwhile, thick layers of snow, warmed slightly by heat escaping from buildings, can slide off roofs in heavy slabs. 'It's about weight and physics,' explains Magnusson in the audio clip accompanying the warning. 'A small icicle might not do much damage, but a large one falling from several stories up is like a dagger. And a sheet of snow is heavy enough to knock someone over or cause serious injury.' The problem is particularly acute in older neighborhoods like Haga or Linnéstaden, with their multi-story buildings and varied rooflines. Modern areas with flat roofs, such as parts of Lindholmen, face different challenges with snow accumulation.

Property owners bear the legal responsibility. Swedish law is clear on this point. The 'Skadeståndslag' (Tort Liability Act) places the duty of care on the person who controls the property. If an icicle or snow mass from a building injures someone or damages property, the owner is typically liable. This isn't just a moral suggestion from the rescue service; it's a legal imperative. Many housing associations ('bostadsrättsföreningar') and private landlords now have standing contracts with roof-clearing services. For the individual villa owner, it means getting out the long-handled roof rake or calling a professional. Ignoring the issue can lead to hefty insurance claims and, more importantly, human tragedy.

A Cultural Dance with Winter

This annual ritual speaks to a broader Swedish approach to nature and community safety. There's a shared understanding that living in this climate requires proactive measures. It's part of 'vinterberedskap' – winter preparedness. You see it in the studded winter tires, the stacks of firewood, and the well-stocked pantries. The icicle warning fits into this mindset. It’s not seen as alarmist, but as sensible. In Stockholm, the same issues occur, often leading to iconic images of the Old Town's narrow streets lined with protective netting. In Göteborg, with its mix of historic brick and modern glass, the solutions must be just as adaptable.

Walking through the city center now, you see the response. Some buildings have simple warning signs reading 'Fara för istappar' (Danger of icicles). Others have erected temporary fences, creating a safe corridor on the sidewalk. In the upscale shopping area of Avenyn, building managers are likely performing daily checks. The contrast is striking. On one side, you have the cozy 'fika' culture inside warm cafés. On the other, a vigilant, outdoor maintenance culture ensuring it's safe to walk to those very cafés. This duality defines the Scandinavian winter experience: creating warmth and community indoors, while managing a sometimes-harsh environment outdoors.

Beyond the Immediate Warning

The rescue service's alert, while focused on physical danger, touches on themes of urban planning and climate adaptation. As winters become more unpredictable with climate change, periods of heavy snow followed by quick thaws and re-freezes may become more common. This could intensify the icicle problem. It prompts questions about building design. Should new constructions in cities like Göteborg, Malmö, and Stockholm incorporate heated gutters or steeper roof pitches as standard? Older, heritage buildings present a tougher challenge, requiring careful, preservation-friendly solutions.

There's also a social dimension. The risk is not evenly distributed. Busy commercial streets get more attention. Quieter residential backstreets might be overlooked. Elderly residents, who may be less steady on icy sidewalks, are particularly vulnerable to both the ice underfoot and the ice overhead. The public warning is therefore also a call for community awareness—to look out not just for oneself, but for one's neighbors. It’s a very Swedish form of collective responsibility, embedded in a simple safety message.

For immigrants and new Swedes, this is a specific lesson in 'how to winter'. The concept of deadly falling ice might be alien to someone from a warmer climate. Integration, in this sense, isn't just about language and employment. It's also about learning to navigate the practical realities of the Nordic environment. Community information in multiple languages, often spearheaded by local municipalities, becomes crucial. It transforms the rescue service's warning from a simple notice into a tool for social inclusion and safety for all residents.

The Human Factor in a Frozen City

At its heart, this story is about people adapting their behavior to their environment. The Göteborg rescue service isn't just fighting fires and responding to accidents; it's working proactively to prevent them. This preventative model is a cornerstone of the Swedish public safety approach. It’s better to warn about icicles than to treat head injuries. This logic extends to everything from cycling helmet campaigns to 'Alkolås' (ignition interlock devices for DUI offenders).

The warning also highlights the informal networks that keep cities functioning. The corner shop owner who knocks down icicles over his entrance. The parent who chooses a safer route for the school walk. The postal worker who notes a dangerous overhang on their route. These small, individual actions, prompted by an official alert, create a layered defense against the hazards of winter. It’s a partnership between authority and citizenry that feels particularly functional in the Swedish context.

As the winter continues, the cycle of snowfall, thaw, and freeze will repeat. The icicles will form again, and the rescue service's message will remain relevant. It’s a reminder that in Sweden, coexisting with nature isn't a romantic ideal—it's a daily practice requiring vigilance and cooperation. The sparkling winter beauty of Göteborg's rooftops comes with a responsibility that everyone shares. The ultimate question is not if the ice will form, but how a modern society organizes itself to live safely alongside it. The answer, from the rescue service to the individual citizen, defines the character of a city in winter.

Will this winter's heavy snow lead to a rethink of how Swedish cities manage their rooftops? Only time will tell. But for now, the message from Göteborg is clear: look up, take care, and respect the frozen power of a Nordic winter.