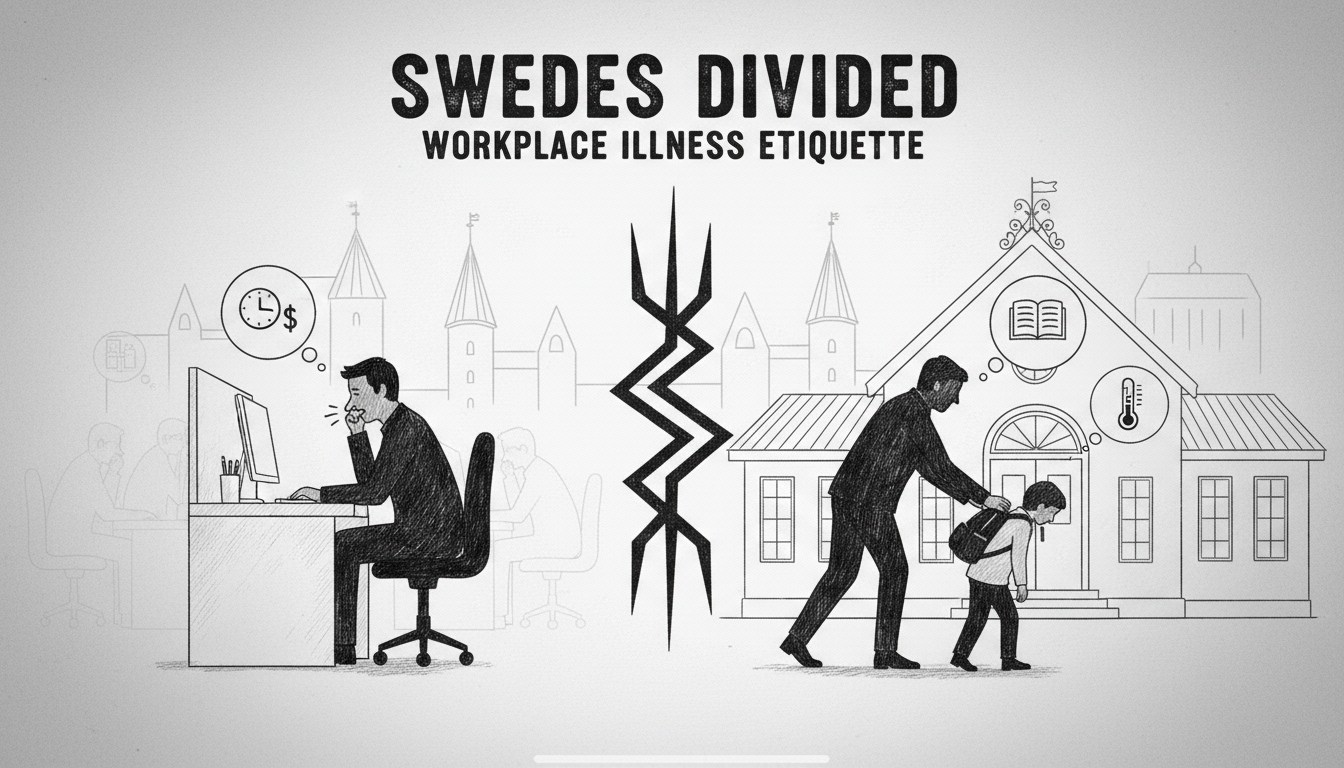

New research reveals Swedes hold conflicting views about showing up sick to work. More than one-third of Swedes believe it's acceptable to go to work with cold symptoms. The survey shows 37 percent consider coughing, sneezing, and nasal congestion no barrier to workplace attendance. Even fever doesn't stop everyone - 18 percent would still report to work with temperatures below 38 degrees Celsius.

Parents appear even more lenient about their children's illnesses. Nearly half of Swedish parents would send slightly unwell children to preschool or school. This attitude persists despite potential infection risks in crowded educational settings.

The findings highlight Sweden's complex relationship with workplace attendance and public health. Swedish work culture traditionally emphasizes responsibility and reliability. Many employees feel pressure to show up regardless of minor ailments. This creates tension between personal health considerations and professional expectations.

Public tolerance for illness in shared spaces remains surprisingly high. Over half of Swedes express little or no irritation when colleagues show up with sore throats or minor colds. Similarly, 55 percent don't mind people coughing in public environments. This suggests Swedes generally accept mild illness as part of daily life.

Infection control experts express concern about these attitudes. They emphasize that even mild symptoms can spread viruses through workplaces and schools. The debate touches on Sweden's sick leave policies and cultural norms around illness disclosure.

International readers might find these attitudes surprising. Many countries encourage staying home at the first sign of illness. Sweden's approach reflects broader Nordic work culture patterns where presenteeism sometimes outweighs infection concerns. The data raises questions about balancing productivity with public health in modern workplaces.

The survey results come during typical cold and flu seasons. They provide insight into how Swedes navigate illness in professional environments. The findings could influence future workplace health policies across Scandinavia.