Residents of Tromsø, Norway face months without sunlight each winter. Yet they experience remarkably low rates of seasonal depression. This northern city challenges conventional wisdom about darkness and mental health.

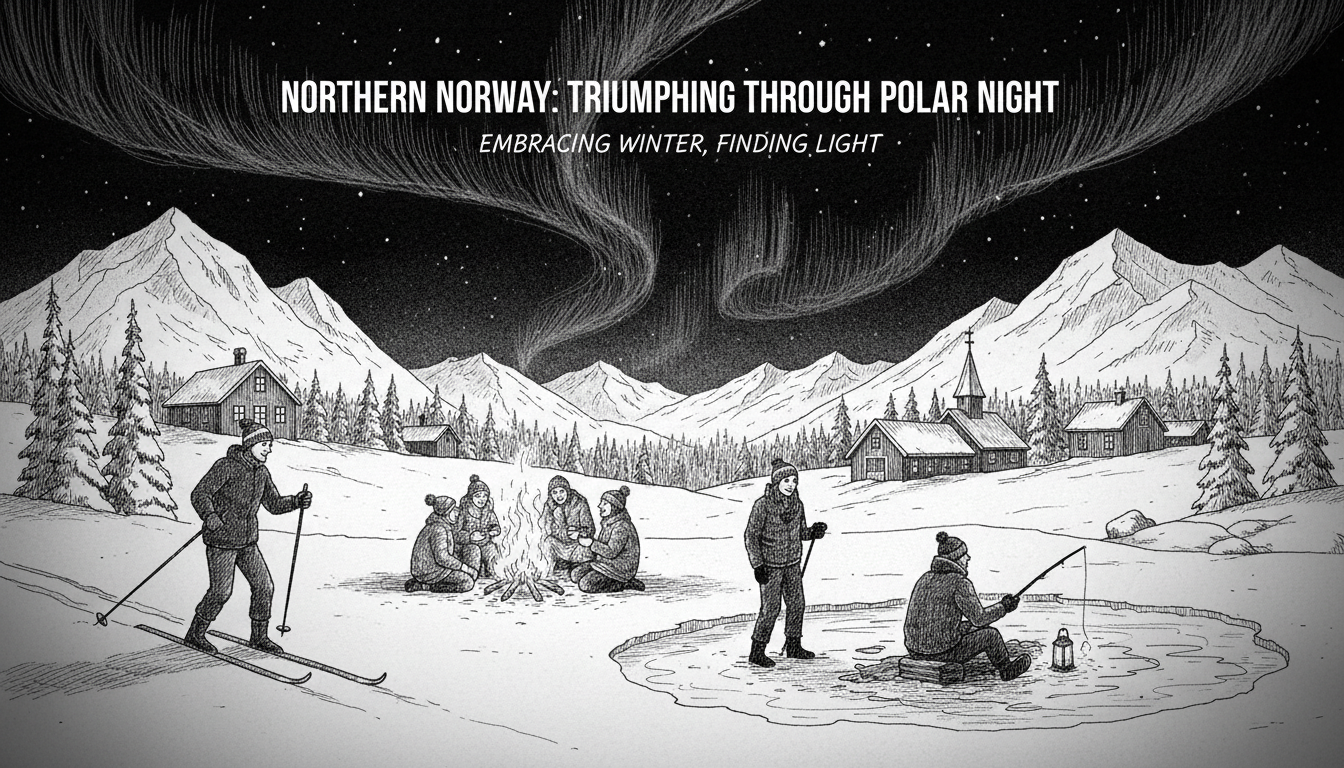

Professor Catharina Elisabeth Arfwedson Wang has lived in Tromsø for 40 years. She also teaches clinical psychology at the world's northernmost university. She explains that locals don't call this period 'the dark time.' Instead, they refer to it as 'the blue time' or 'color time.' The darkness isn't truly dark, she notes. Faint sunlight, moonlight, and especially northern lights paint the white snow with vibrant colors.

Research confirms something remarkable about Tromsø residents. They don't suffer more seasonal depression than people living near the equator. This finding contradicts expectations about winter darkness and mental health. The professor has studied depression for three decades while living under the polar night herself.

So what do Tromsø residents do differently? They maintain closer connections to nature and adapt to seasonal changes. Winter becomes something to experience rather than endure. Winter sadness doesn't dominate conversations here, the professor observes. City dwellers have more electric light, which seems more civilized but also more artificial. In Tromsø, people can actually see the sky and stars clearly.

Outdoor activity continues throughout the dark period. Residents move outside regularly, even when others might consider conditions too cold and wet. A local saying captures this attitude well: There's no bad weather, only bad clothing.

Some people do experience sleep problems during the dark months. But individuals have considerable control over how darkness affects them. The professor emphasizes accepting that body and mind feel different in winter. People shouldn't maintain the same expectations for themselves during this period. However, this acceptance shouldn't lead to complete inactivity.

She offers practical guidelines for handling darkness effectively. Cultivate strong social relationships. Maintain good sleep habits with consistent daily rhythms. Stay active, even if just through daily walks. Seek available light whenever possible. Workers with midday breaks might consider eating lunch outside. The professor adopted another solution herself: getting a dog. A dog will ensure its owner goes outside regularly, regardless of light conditions.

This Norwegian approach to winter darkness offers valuable lessons. It demonstrates how cultural attitudes and lifestyle choices can overcome environmental challenges. The Tromsø example shows that human adaptation to extreme conditions involves both practical strategies and mental reframing. Their experience suggests that seasonal depression isn't an inevitable consequence of limited sunlight. Instead, it reflects how communities choose to respond to their environment.

Northern Norway's relationship with darkness provides insights for people everywhere experiencing winter. The key lies in embracing seasonal changes rather than fighting them. Active engagement with nature, social connection, and realistic self-expectations create resilience. These principles apply beyond the Arctic Circle to anyone facing challenging seasonal conditions.