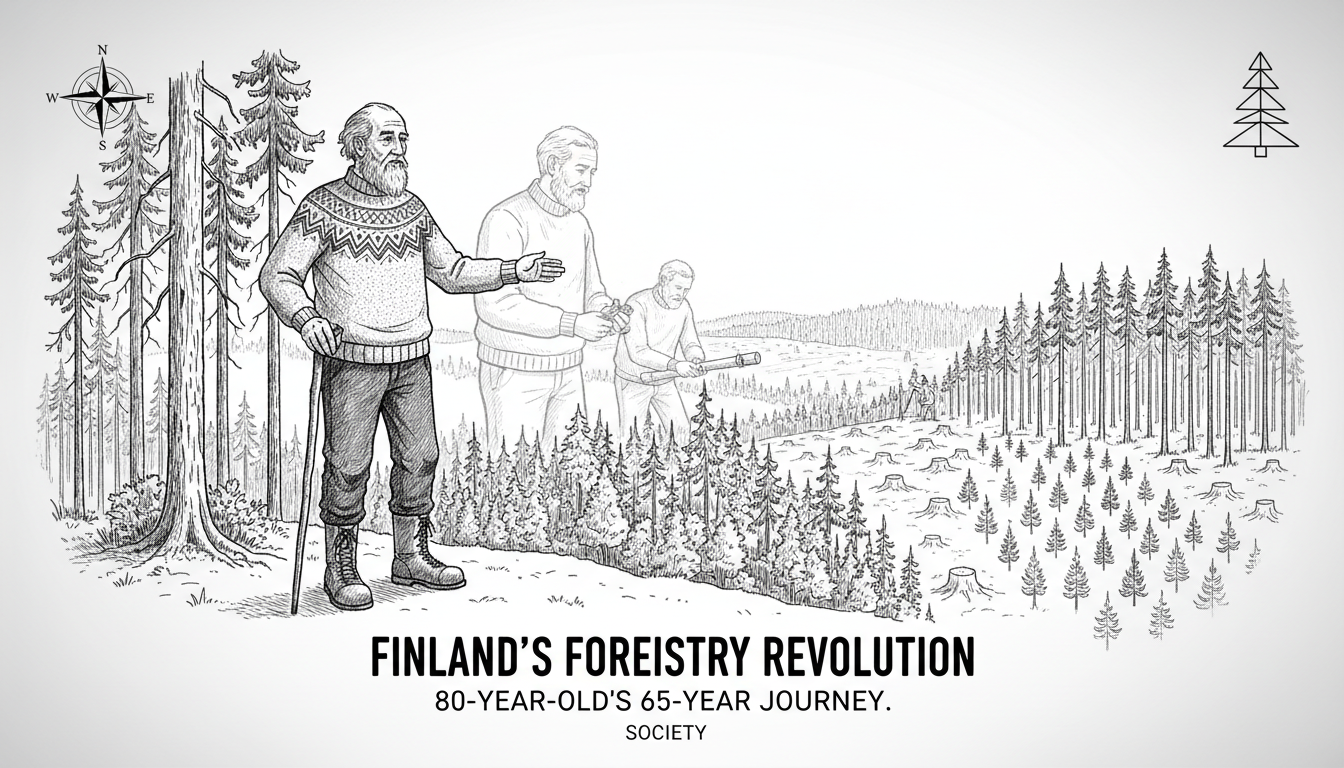

Finnish forestry has undergone a transformation from horse-drawn sleds to computer-controlled harvesters over the past seven decades, a journey embodied by 80-year-old entrepreneur Kari Lahtinen. Lahtinen, who co-founded the logging company Lahtinen Forest, started driving timber sleds at just 15 years old when his father fell ill. "You just have to go," his father told him after taking on a contract, launching a career that has spanned the industry's most dramatic technological and economic shifts.

"The development arc in forestry during my lifetime has been truly massive and revolutionary," Lahtinen said, reflecting on his 65 years in the trade. His early days involved manually lifting logs with timber tongs onto a sled pulled by a horse and a double sled runner, work he described as extremely heavy even for a large, sturdy teenager. This personal history mirrors the national story of a sector that has moved from sheer muscle power to mechanized precision, all while remaining the backbone of Finland's export economy.

From Axes to Algorithms: A Sector Transformed

Lahtinen's entry into logging in the late 1950s coincided with the very beginning of forestry's mechanization in Finland. For centuries, the industry relied on axes, handsaws, and horse power. The mid-20th century introduction of chainsaws and tractors marked the first major leap. "We were at the cusp of change," Lahtinen noted, describing how manual felling and horse transport gradually gave way to new machinery. This shift was not just about tools; it altered the fundamental relationship between the worker and the forest, increasing scale and output dramatically.

Today, Finland's forests cover over 75% of the country's land area, making it one of Europe's most forested nations. The forest industry contributes a substantial 20% of Finland's total export revenue, a figure that underscores its enduring economic importance. Modern harvesters, which can fell, delimb, and cut trees to length in one automated process, are a world away from Lahtinen's first sled. These machines are guided by sophisticated software that optimizes cuts for value, representing a shift from physical labor to digital management.

The Economic Backbone and Its Balancing Act

The financial significance of forestry to Finland cannot be overstated. It is a primary industry for many rural regions, providing direct employment and supporting related sectors like transport and machinery manufacturing. The statistic that Finland's annual forest growth currently exceeds harvest volumes is a key point of pride and a foundation for the sector's future. It suggests a renewable resource base, but experts caution that this aggregate figure must be managed with care at the local level to ensure biodiversity and ecosystem health.

Sustainable forest management has become the central tenet of modern Finnish forestry policy. The focus has expanded from sheer volume and efficiency to include conservation goals, protection of watercourses, and the preservation of decaying wood habitats crucial for many species. "The conversation has moved beyond just cubic meters of timber," said one forestry expert familiar with the Nordic model. "It's now about the forest's multiple roles: as an economic asset, a carbon sink, and a biological network." This balance is the industry's contemporary challenge.

The Human Story in a Mechanized Landscape

Kari Lahtinen's longevity in the field offers a unique perspective on these changes. His company, Lahtinen Forest, adapted through the decades, moving from manual contracts to operating advanced machinery. His personal motto, hinted at in the Finnish phrase "nuorena pittää yrittää" (you have to try when you're young), speaks to the resilience and adaptability required. The workforce has transformed alongside the technology; the traditional "tukkijätkä" or lumberjack, reliant on brute strength, has been largely replaced by skilled machine operators and forestry technicians.

This evolution has reduced the physical toll of the work but introduced new demands for technical training and continuous learning. The social structure of forestry work has also changed, moving from tightly-knit, seasonal logging camps to more dispersed, year-round machine operations. Lahtinen's story connects these two eras, embodying the knowledge transfer from one generation of forest workers to the next, even as the tools of the trade became unrecognizable to his younger self.

Future Forests: Sustainability as the New Paradigm

Looking ahead, the Finnish forestry sector faces a complex set of expectations. It is called upon to supply renewable raw materials for the traditional pulp and paper industry and the growing wood construction sector, while simultaneously contributing to the bioeconomy and climate goals. Forests are Finland's largest natural carbon sink, and their management is directly linked to the country's ambitious carbon neutrality targets. The industry is investing in new technologies, such as precision forestry that uses drones and satellite data, to meet these dual demands of production and preservation.

The debate often centers on the intensity of forest management. Practices like clear-cutting, which became efficient with mechanization, are now scrutinized for their ecological impact. Alternatives, such as continuous cover forestry where trees are selectively harvested, are gaining attention for their biodiversity benefits, even if they are sometimes less economically efficient in the short term. "The revolution isn't over," the forestry expert noted. "The next phase is about smarter, more nuanced use of the forest, integrating economic and environmental values into every decision."

A Living Legacy in the Woods

For Kari Lahtinen at 80, the forest is both a workplace and a living archive of change. The clear-cuts he worked on as a young man have grown into new forests, which have themselves been harvested, in a cycle he has witnessed multiple times. His career, from horse sleds to harvesters, provides a human-scale narrative for a national industrial transformation. It is a story of adaptation, reflecting Finland's own relationship with its most dominant natural resource.

The foundational role of forestry in Finland's economy and identity remains, but its expression is continually evolving. As the industry navigates the pressures of climate change, biodiversity loss, and global market demands, the lessons from its past transformations will be crucial. The challenge for today's foresters is to manage this renewable resource with a legacy mindset, ensuring that the forests that have supported generations of Finns, from tukkijätkä to technician, remain vibrant and productive for generations to come. The arc of development continues, now bending toward sustainability.