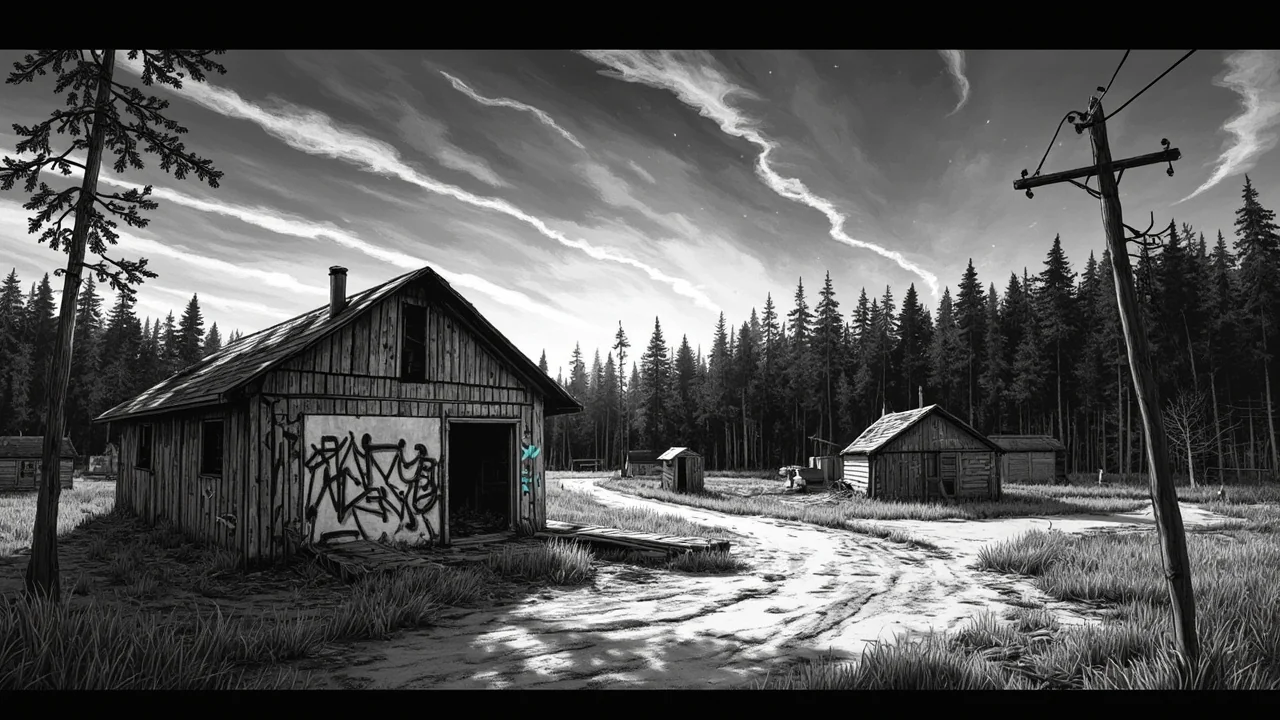

Finland's rural communities are confronting a wave of destructive vandalism that is eroding public services and social trust. In Korvenkylä, a village of a few hundred residents, a year-long spree of targeted damage has burned a sports shed, wrecked ski trails with ATVs, torn up a football pitch, defaced traffic signs and new bus shelters, and smashed equipment in a community-built playground. The final blow came last autumn when persistent harassment and mess at the local library forced officials to cancel all unsupervised evening and weekend hours, effectively shutting residents out of a vital community hub for most of the week.

"Residents feel like their time to borrow and read has been taken away," says Harri Matikainen, vice-chairman of the Korvenkylä village association. His statement captures the profound frustration felt by active community members who watch their collective work destroyed by a handful of individuals. The library, once a symbol of quiet civic life and lifelong learning, now stands with restricted access, its doors locked during the very hours working families and students need it most.

A Pattern of Destruction Across the Country

Korvenkylä's ordeal is not an isolated incident but part of a troubling national pattern of anti-social behavior targeting public spaces. In Vuoksenniemi, vandals attempted to block a library toilet, smeared windows, and threw spices over books. Further incidents recorded across Finland include jumping on tables and trashing toilets in Pyhtää, locking other patrons out of facilities in Mäntyharju, and in Hamina, where a toilet bowl was smashed and seat cushions thrown out of a window. In Lapinlahti, libraries dealt with vomiting, and in Joensuu, the disruption became so severe that police were finally called and a criminal report filed.

This nationwide trend points to a deeper social malaise beyond simple teenage mischief. The targets are consistently shared, communal assets: libraries, sports facilities, and playgrounds. The acts are often senseless, like ruining meticulously groomed ski trails, which provide free winter recreation for all ages. Each incident represents a direct attack on the Finnish concept of yhteisöllisyys, or community spirit, and the principle of common access to nature and culture.

The High Cost of a Locked Library Door

The restriction of Korvenkylä's library hours reveals the disproportionate impact of vandalism on small communities. In practice, the library became accessible only on Monday evenings until 9 PM and Wednesday afternoons until 4 PM. For a rural village, the library is far more than a book-lending service; it is a warm, quiet space for remote workers, a meeting point for the elderly, a critical resource for students without home internet, and a venue for club meetings and children's story hours. Removing its evening and weekend availability cuts a vital artery of community life.

Finland's library system is globally renowned, a cornerstone of the welfare state designed to guarantee equal access to information and culture regardless of location or income. The vandalism in Korvenkylä and elsewhere directly undermines this principle. It creates a two-tier system where well-behaved, law-abiding citizens in smaller towns lose services because authorities cannot guarantee security. The solution of locking doors is a pragmatic failure that punishes the community for the crimes of a few.

"The village association believes that by working together, things can be put right," the source material states, highlighting the resilient but weary attitude of local volunteers. These individuals often dedicate unpaid hours to maintaining the very facilities that are destroyed. The cycle is demoralizing: community activists raise funds, secure grants, and volunteer labor to build a new playground or refurbish a sports field, only to see it damaged within weeks. This erodes the volunteer base essential for rural survival.

Searching for Solutions Beyond Policing

The response to this crisis involves a complex balance between security, social services, and community engagement. Increased surveillance, such as cameras at sports grounds, is a common but unpopular first step, seen as contrary to the open, trusting nature of Finnish village life. Municipalities face tight budgets, making costly repairs and constant security patrols unsustainable. Some towns, like Joensuu, have escalated responses to criminal reports, but this relies on identifying perpetrators and the justice system providing meaningful consequences.

Experts in youth work and social policy suggest the vandalism often stems from profound boredom and a lack of positive engagement, particularly among young people in areas with limited employment and entertainment options. The destruction of sports facilities is especially ironic, as it eliminates the very venues for healthy activity. Comprehensive solutions likely involve investing in youth outreach, creating structured after-school programs, and providing spaces where young people can socialize constructively without fee barriers. This requires cooperation between municipalities, schools, sports clubs, and social services.

Finnish law and municipal policy must also clearly define the thresholds for intervention. When does nuisance behavior become criminal damage? Who bears the cost of repeated repairs? The situation in Korvenkylä shows that by the time a library's operating model must change, the problem is already severe. Proactive, early intervention strategies are needed to identify at-risk youth and offer alternatives before a pattern of destruction sets in.

The Resilience of the Village Association

Despite the setbacks, the Korvenkylä village association embodies the Finnish concept of sisu – a stoic determination. Their belief in collective action remains. The path forward is arduous, involving not just repair work but rebuilding a sense of collective ownership and pride among all residents, especially the young. Potential initiatives could include participatory budgeting for youth projects, involving teenagers in the planning and building of new facilities, or creating mentorship programs that connect them with older community members.

The vandalism crisis is a test for the social fabric of rural Finland. It questions whether the traditional models of trust and open access can survive without adaptation. The solution will not come from Helsinki alone but from a hybrid approach: supportive national frameworks for youth services combined with hyper-local, community-driven engagement. The goal is to transform the vandals from outsiders destroying a community into stakeholders protecting it.

As Harri Matikainen and his colleagues in Korvenkylä look at their damaged sports shed and restricted library schedule, they face a fundamental question. Can a community rebuild its physical spaces while also repairing the invisible social contracts that have been broken? The answer will determine not just the state of their playgrounds and libraries, but the future vitality of rural Finland itself. The work continues, one repaired piece of equipment, one conversation with a young person, and one restored library hour at a time.