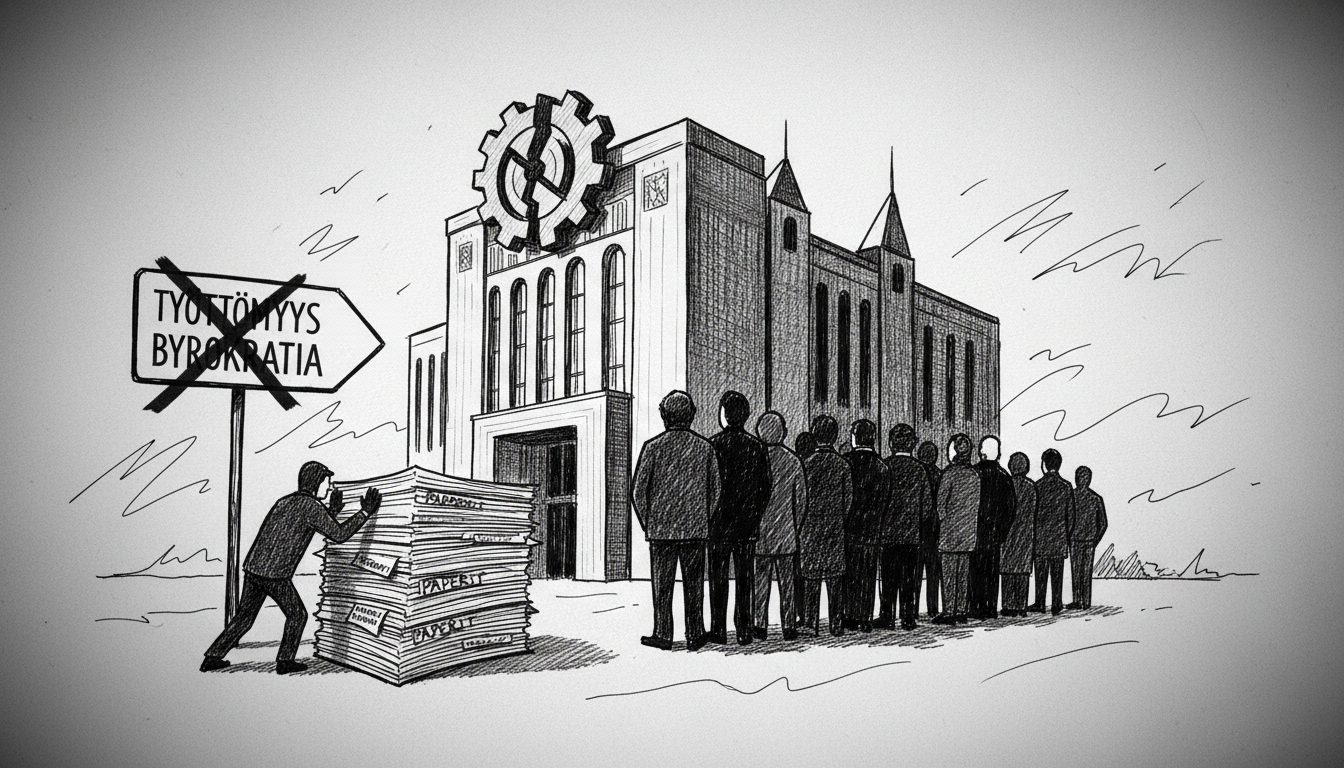

Finland’s unemployment system demands that Heidi Ruohola abandon her studies to receive benefits, sparking a national debate on rigid welfare rules. In late November, the 34-year-old from Ulvila became unemployed after a fixed-term work contract ended. When she contacted the Public Employment and Business Service (TE Office) to register, she received instructions that left her stunned. Officials informed her she must formally terminate her ongoing university studies in educational science to qualify for unemployment payments. This interaction highlights a persistent friction point within Finland's otherwise admired social safety net, where the mandate to seek work actively can directly conflict with efforts to upskill.

A Personal Clash with Systemic Rules

Heidi Ruohola’s initial reaction was one of sheer disbelief. "First came the shock. As if it wasn't enough that my job ended, and then this on top of it," Ruohola said. The TE Office's position was rooted in a standard interpretation of Finland's Unemployment Security Act. The law requires benefit recipients to be available for full-time work and to actively seek employment. Full-time study is typically viewed as compromising this availability. For Ruohola, the demand felt counterproductive. Her studies were partially complete and represented a strategic investment in her future employability within the education sector, a field with known demand in Finland. Her choice was stark: halt her progress toward a degree or forfeit crucial income support during her job search.

The Mechanics of a Inflexible Rule

The rule that ensnared Ruohola is not a secret, but its application often catches citizens by surprise. Finland's unemployment benefits are administered through a dual system. The Social Insurance Institution of Finland (Kela) provides the basic unemployment allowance, while earnings-related benefits are managed by unemployment funds, usually tied to trade unions. Eligibility for both, however, is gatekept by the TE Offices. Their caseworkers assess whether an individual's activities align with the core requirement of being ready to accept a full-time job offer within three months. Formal education leading to a degree is frequently seen as a primary commitment, thus disqualifying the individual. In 2023, approximately 7% of Finland's workforce was unemployed, navigating these precise regulations.

There are narrow exceptions. Short courses approved by the TE Office, such as those directly enhancing job-search skills or specific vocational training, may be permitted. Studying part-time while explicitly demonstrating full-time job availability can also be acceptable. The system's rigidity, experts argue, lies in its binary framing and inconsistent application across different offices. "The system is designed to prevent abuse, which is valid, but it often fails to distinguish between someone avoiding work and someone genuinely improving their long-term prospects," commented a social policy researcher from the University of Helsinki, who requested anonymity due to ongoing government consultations. This creates a postcode lottery of sorts, where outcomes can depend on the interpreting caseworker.

From Disbelief to Successful Appeal

Instead of complying, Heidi Ruohola decided to challenge the decision. She lodged a formal complaint, arguing that her studies did not prevent active job seeking and were, in fact, aligned with her career trajectory. This step is one many unemployed individuals do not take due to the complexity, time required, or fear of bureaucratic repercussions. Her appeal triggered a mandatory re-evaluation. After review, the TE Office reversed its position. Officials concluded that Ruohola’s specific study plan and her demonstrated commitment to job-seeking were, in fact, compatible. She was granted permission to continue her studies while receiving unemployment benefits. Her case is a small but significant victory, proving that the system's determinations are not always final.

A Broader Policy Dilemma for Helsinki

Ruohola’s experience taps into a longstanding debate in the Finnish Parliament, the Eduskunta. Lawmakers from across the political spectrum have grappled with modernizing the social security system to better support lifelong learning. The Center Party and the Left Alliance have periodically pushed for more flexibility, arguing that an evolving economy requires a workforce capable of retraining. The National Coalition Party and the Finns Party often emphasize the fiscal responsibility and work-first principle underlying the current rules. This tension reflects a broader European Union policy struggle, balancing the Lisbon Strategy's goals for a skilled workforce with the need for functional active labor market policies.

Recent governments in Helsinki's bustling government district have made tentative steps. Previous administrations have piloted programs like "oskari," which allowed limited study while on benefits, but these have been temporary and limited in scope. The current ruling coalition, led by Prime Minister Petteri Orpo, has prioritized reducing unemployment through work-based incentives but has yet to announce major reforms to the study-benefit conflict. Social Affairs Minister Sanni Grahn-Laasonen has acknowledged the need for a "more intelligent" system but cautioned that any changes must ensure the primary goal of unemployment security—finding work—is not weakened.

The Human and Economic Cost of Rigidity

Policy analysts warn that the current inflexibility carries a dual cost. First, it creates personal hardship and stress for individuals like Ruohola, potentially pushing them to abandon education that would make them more resilient against future unemployment. Second, it presents a macroeconomic cost. Finland faces significant skill shortages in sectors like technology and healthcare. Deterring the unemployed from acquiring relevant skills contradicts national economic objectives. A report from the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra recently noted that future labor market policies must integrate security with flexibility for learning, a model sometimes called ‘security in change’.

The Finnish experience contrasts with some adjustments seen in other Nordic neighbors. Sweden, for instance, generally allows for full-time studies for up to 12 months while receiving activity support, provided the studies are deemed to improve employability. Denmark’s system also incorporates more structured education and training phases within its unemployment support framework. Finland’s adherence to a stricter interpretation is seen by some experts as an outlier that may need recalibration as labor markets become more dynamic.

A System in Need of Nuance

Heidi Ruohola’s successful appeal is a microcosm of a needed shift. It proves that when examined on a case-by-case basis with nuance, studying and job-seeking can be complementary, not contradictory. The challenge for Finnish policymakers is to institutionalize this nuance. This could involve clearer statutory guidelines that empower TE Office workers to make more individualized assessments, investing in their training to evaluate the relevance of studies, or creating a formalized "right to study" period within the unemployment benefit timeline.

The core question for the Eduskunta is this: Is Finland’s social security system designed merely to maintain people during short-term joblessness, or is it also a tool to actively build a more competent and adaptable workforce for the decades ahead? Heidi Ruohola’s quiet act of defiance did not just secure her own student benefits; it voiced a pressing question about the very purpose of welfare in a modern knowledge economy. As technology reshapes jobs at an accelerating pace, the answer to that question will define Finland’s competitive edge and social cohesion. The bureaucracy’s next move will be closely watched by thousands of Finns seeking to better themselves while between jobs.