Iceland's Westman Islands host a unique troll parade this weekend during the annual Þrettándinn festival. The remote archipelago transforms into a vibrant stage for folklore and community celebration. President Halla Tómasdóttir and her husband Björn Skúlason are visiting officially, joining what locals call the nation's largest family-friendly winter party. This event underscores Iceland's deep connection to its myths and tight-knit island communities.

A Festival Shifted for Community

Most Icelanders celebrate Þrettándinn, or Twelfth Night, on January 6th. Vestmannaeyjar islanders, however, moved their main festivities to the first convenient weekend of the new year. This pragmatic shift allows for a full, immersive celebration. Kristleifur Guðmundsson, supervisor of the so-called troll workshop, gets a week off from his job on the Herjólfur ferry for the event. He describes the festival as a winter highlight unlike any other. "This is essentially a winter festival where we dedicate the whole weekend to Þrettándinn, which is why we move it to a weekend," Guðmundsson said. "This is probably the biggest family and entertainment festival in the country, maybe except for Þjóðhátíð." The adjustment reflects the island's independent spirit and logistical savvy.

The weekend schedule is packed, creating a continuous flow of activity. Events include the Grímuball on Friday and the Þrettándaball on Saturday night. The climax involves a fireworks display, a torchlit procession, a bonfire, and the iconic troll march. This structured yet joyful chaos binds the community together. It offers a stark contrast to Reykjavik's more dispersed winter events. The islands' small size fosters an intimate, all-encompassing experience for residents and visitors alike.

The Troll Parade: A Living Tradition

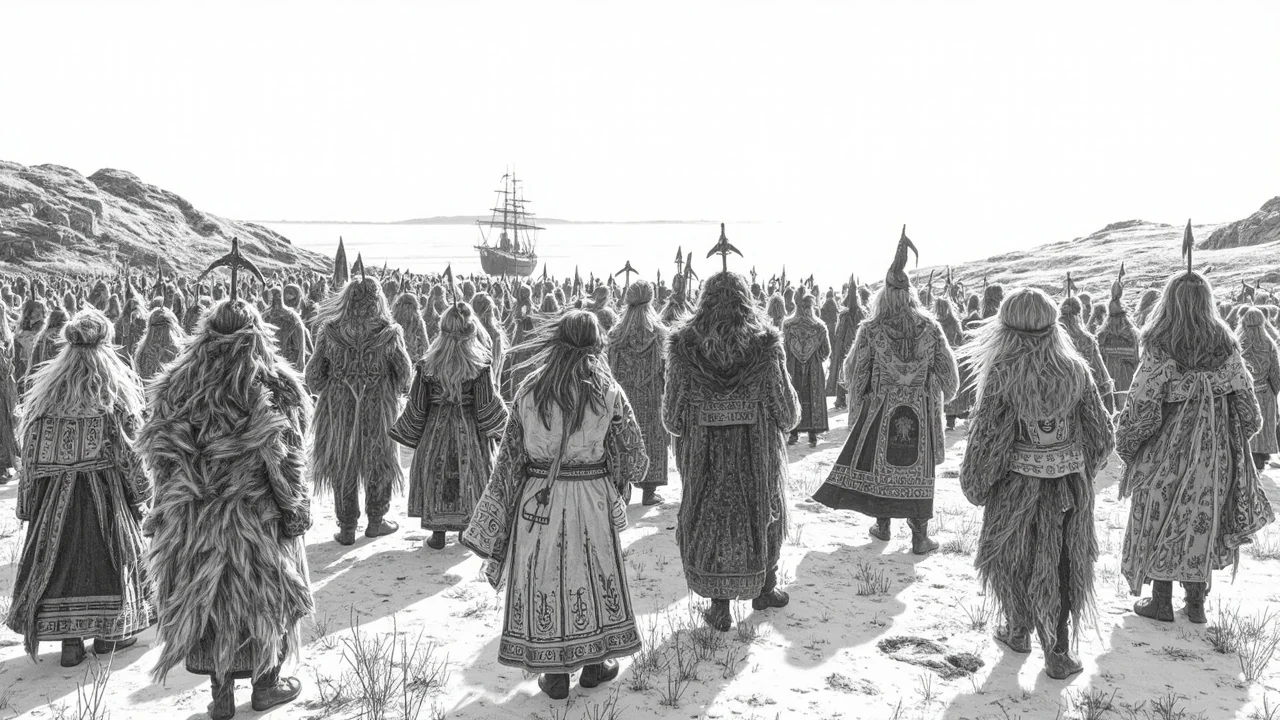

The troll parade is the festival's visual and cultural heart. Approximately one hundred islanders don elaborate troll costumes, weaving through the town's streets. "It's been a tradition since I don't know when," Guðmundsson noted. "It's been around for a million years, and you really just have to experience it to understand how magnificent it is." The tradition's unclear origins add to its mythical charm. It represents a direct, playful engagement with Icelandic folklore, where hidden people and giants are part of the national psyche. The parade is not a commercial spectacle but a communal act of storytelling.

Costumes range from hairy giants to rock-like creatures, often handmade with care. This DIY ethos is key to the event's authenticity. It echoes broader Nordic trends of folk revival and community art. The parade turns the island's volcanic landscape into a narrative backdrop. For an environmental correspondent, this tradition highlights a sustainable cultural practice. It relies on human creativity rather than consumption, reinforcing local identity without heavy resource use. It is a testament to the islands' resilient cultural ecosystem.

Presidential Visit and Political Symbolism

President Halla Tómasdóttir's official visit intertwines with the festival's schedule. Her participation signals recognition of regional cultural significance. It also aligns with her role in fostering national unity. The president's presence at such a grassroots event is noteworthy. It suggests a political appreciation for traditions that strengthen social fabric outside the capital. This visit can be seen as a nod to Iceland's decentralized cultural vitality. It reminds the Althing in Reykjavik that national identity is built in places like Vestmannaeyjar.

Political analysts might view this as soft diplomacy within Iceland's regions. The president engaging with troll parades and community balls builds connective tissue. It contrasts with more formal state functions. In a Nordic context, such visits are common for monarchs and presidents, emphasizing cultural patronage. For the Westman Islands, it validates their unique celebrations. It also brings national media attention to the archipelago's way of life, potentially boosting winter tourism in a balanced manner.

Cultural Analysis from a Nordic Perspective

From a Nordic viewpoint, the Westman Islands festival shares traits with other regional winter celebrations. However, its focus on trolls is distinctly Icelandic. Norway and Sweden have their own folklore festivals, but Iceland's integration of myth into modern community life is pronounced. This event is less about historical reenactment and more about living adaptation. It functions as a "real sect" of joy, as the original headline quipped, demonstrating how folklore can create powerful social cohesion.

The festival's timing, shifted from the official holiday, shows practical Nordic adaptability. Communities across Scandinavia often adjust traditions to fit contemporary life. The event's scale, described as rivaling the national festival Þjóðhátíð, is significant. It highlights how island communities can produce cultural exports that captivate the entire nation. The environmental angle here is subtle but present. The festival uses the natural setting—wind-swept streets, ocean vistas—as an integral part of its atmosphere, promoting a sense of place without degrading it.

Community Impact and Economic Echoes

For the 4,300 residents of Vestmannaeyjar, this festival is a major annual undertaking. It involves volunteers, local businesses, and families. Kristleifur Guðmundsson's week-long preparation pause is a microcosm of community-wide effort. The festival injects energy into the quiet January period. It may attract some tourists, but its primary audience is locals. This inward focus is its strength. It preserves tradition for tradition's sake, not for external validation. In an era of globalized culture, that is a rare and valuable stance.

The fishing industry, the lifeblood of the islands, likely sees a brief lull or participation from workers. The festival acts as a social release valve after the demanding fishing seasons. It reinforces community bonds that are crucial for survival in a remote location. Economically, it supports local vendors and craftspeople who make costumes and organize events. This creates a circular economy of cultural production. The president's visit may indirectly highlight the islands' economic importance, tying cultural heritage to sustainable industry.

The Future of Folk Traditions in Iceland

This festival raises questions about the preservation of Icelandic folklore in the 21st century. As younger generations migrate to Reykjavik, such traditions face challenges. Yet, the vibrant participation in the troll parade suggests enduring appeal. The event's informal, inclusive nature—allowing anyone to join as a troll—ensures its renewal. It avoids becoming a museum piece. Instead, it evolves while retaining core elements. This is a model for other Nordic communities seeking to keep traditions alive.

Environmental considerations for such events are increasingly relevant. The torchlit procession and bonfire are managed locally with safety in mind. The festival's carbon footprint is minimal compared to large-scale concerts, relying on local resources and human power. This aligns with Iceland's broader goals of sustainable living. The troll parade, in its whimsical way, celebrates the human spirit without excessive consumption. It is a form of cultural sustainability that complements environmental stewardship.

A National Mirror in an Island's Celebration

Ultimately, the Westman Islands' Þrettándinn festival is a mirror for Iceland itself. It reflects a nation deeply rooted in story, community, and adaptive resilience. The trolls dancing through the streets are more than costumes; they are symbols of a collective imagination. President Tómasdóttir's presence acknowledges this. In a Nordic region often focused on innovation, this event is a reminder of the power of tradition. It shows that in Iceland, even the highest office can find wisdom and joy among trolls and islanders. As the fireworks fade over the Atlantic, the warmth of this community celebration lingers, challenging other regions to cherish their own unique sparks of culture.