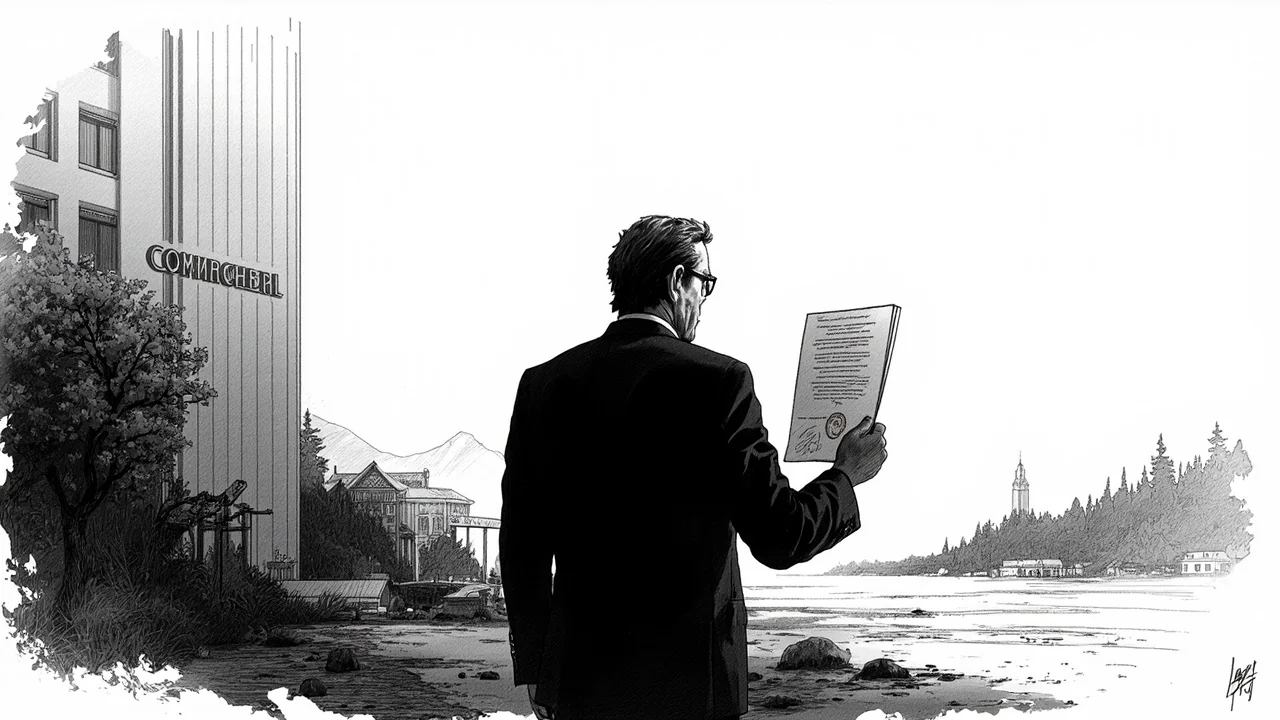

Norwegian regulatory enforcement has delivered a 375,000 kroner blow to a major domestic moss harvesting firm, mandating strict work-hour logging for its migrant pickers in remote forests. Norske Moseprodukter AS, a Rendalen-based company with annual revenues near 51 million kroner, lost its court case against the state this week, upholding a penalty from the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority.

Company owner Bjørn Dingstad reacted with frustration, labeling the requirements as impractical "desktop bureaucracy." The core legal dispute centered on whether Norwegian working time regulations applied to the 30-40 seasonal pickers, who primarily come from Vietnam, Ukraine, and Poland. The court ruled definitively that they did, classifying the migrant pickers as "extra vulnerable workers" and siding with the state's demand for formalized hour tracking.

A Clash Over Control and Practice

The company's defense hinged on the argument that its pickers operated with significant autonomy. Dingstad described workers who organized themselves into groups based on family and friendship ties, set their own schedules based on weather and sunlight, and were paid on a piece-rate system. He contended this structure made them akin to self-employed contractors, not traditional employees requiring meticulous time oversight.

"That there should be time sheets out in the forest where they work at all hours of the day... these are people from another time zone. For them, it's not so important if it's daytime or the middle of the night," Dingstad said, emphasizing the practical disconnect. He argued that enforcing standardized logs was unfeasible for workers living isolated in the woods and impractical for employers managing significant time differences with workers' home countries.

The State's Duty of Care Argument

The Labour Inspection Authority's position, now validated by the court, is grounded in protective labor law. The ruling underscores the state's view that piece-work and remote locations do not negate an employer's fundamental responsibility to monitor working hours to prevent exploitation and ensure health and safety standards. This is particularly pointed given recent, unrelated incidents where migrant workers in Norway have faced dangerous conditions.

The court's designation of the pickers as "extra vulnerable" is a critical legal finding. It reflects an acknowledgment of the potential power imbalance between seasonal migrant laborers and their employer, and the specific risks they may face due to language barriers, unfamiliarity with Norwegian rights, and economic necessity.

Operational Realities in the Rendalen Forest

The operational model described by Norske Moseprodukter highlights a traditional, almost informal, industry facing modern regulatory scrutiny. Moss picking for decorative use is weather-dependent and sporadic, leading to non-standard work patterns. Dingstad portrayed a system built on trust and self-management, now challenged by a framework designed for more conventional, fixed-location employment.

"They live completely isolated deep in the forest. They have their own completely separate routines. And they have their family and friends in their home country, it's no use calling them from here in the middle of the day if there's a nine-hour time difference. It just becomes nonsense altogether," Dingstad stated, painting a picture of a workflow inherently at odds with bureaucratic logging.

The Path Forward for Seasonal Work

The ruling does not shut down the moss harvesting business, but it imposes a new cost of compliance. The company must now develop a method to log hours for its dispersed, autonomous pickers—a logistical challenge that Dingstad views as burdensome and somewhat absurd. How this is implemented—whether through digital solutions, adapted record-keeping, or a restructuring of the work relationship—will determine the practical impact.

For Norway's regulatory bodies, the victory reinforces their authority to apply core labor standards even in non-traditional sectors. It sends a clear message that the vulnerability of the worker is a primary consideration, superseding arguments about operational practicality in matters of basic rights and safety oversight. The decision affirms that in the Norwegian legal landscape, the duty to protect vulnerable workers from potential overwork and exploitation is non-negotiable, regardless of where the work takes place.

The final outcome is a clarified standard: even in the deep forests of Rendalen, the right to regulated working hours must be upheld, and the responsibility for ensuring it rests firmly with the employer. The moss pickers, deemed vulnerable by the court, now have that principle officially watching over them, codified not just in law books but in a binding ruling against a reluctant company.