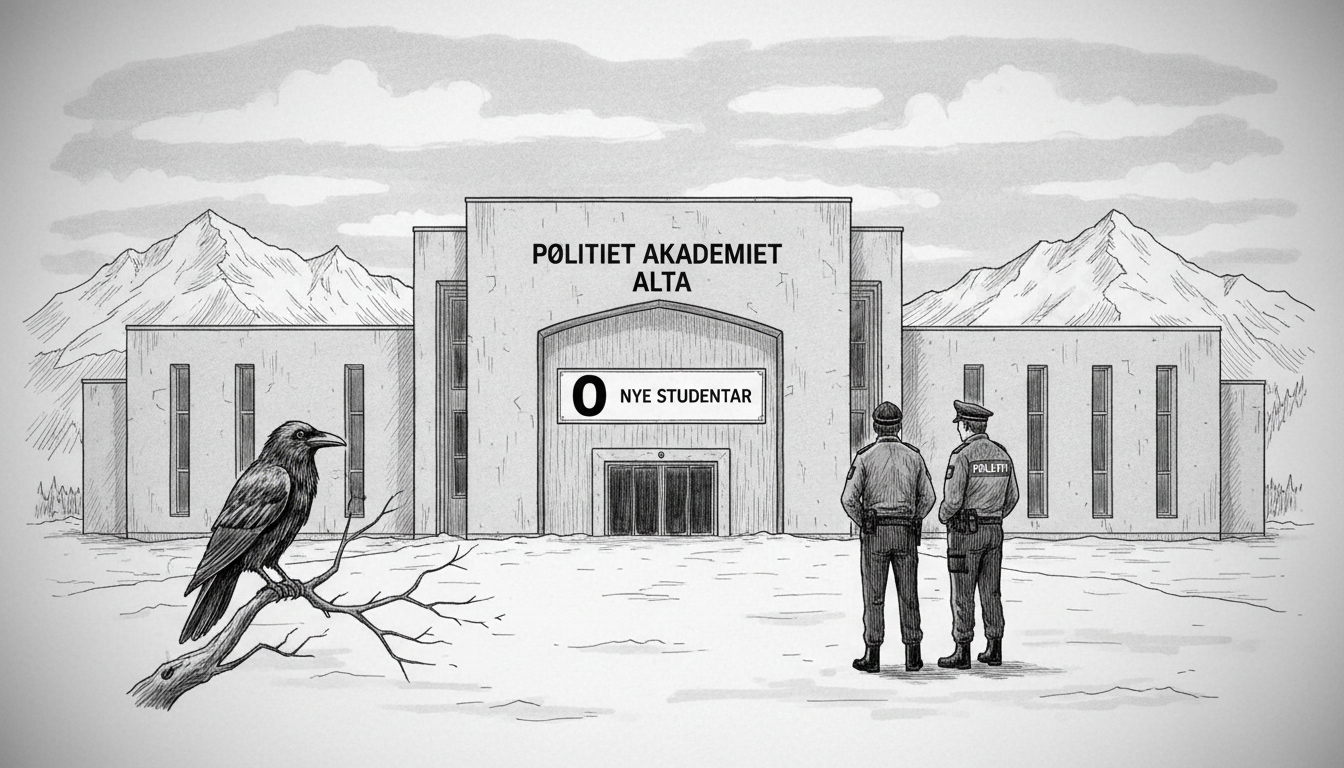

Norway's police training system faces a critical test after the government decided against funding a new student intake for the Police University College campus in Alta for 2026. The decision halts admissions just one year after the northernmost police academy in the world opened its doors, raising serious questions about regional recruitment and national policing strategy. The campus, located 500 kilometers north of the Arctic Circle, will see no new first-year students next year due to a lack of state funds.

Chief of Police Ellen Katrine Hætta, who leads the Finnmark police district, has voiced strong criticism. She argues that evaluating an initiative based on just one student cohort provides an insufficient foundation for judgment. "To only evaluate one intake does not give enough of a basis to assess the entire arrangement," Hætta said in a statement. Her district, Norway's largest and most sparsely populated, covers a vast Arctic territory bordering Russia and Finland.

A Sudden Stop for a High-Demand Program

The Alta campus launched in August last year with significant local fanfare. It represented a concrete step toward decentralizing police education and addressing chronic recruitment shortages in the north. The initial demand was overwhelming: 256 applicants competed for just 24 study places, an application-to-place ratio exceeding 10:1. This demonstrated clear local and regional interest in a policing career, provided the training was accessible.

The students who began last autumn will continue their three-year bachelor's program in Alta until graduation. However, the absence of a new cohort in 2026 creates an immediate operational gap. It disrupts the campus's rhythm, affects local economic activity tied to the school, and sends a discouraging signal to potential future applicants in Finnmark. The decision was made during the national budget process, where the Police University College's total allocations and study place distribution are set.

The Regional Recruitment Challenge

Experts in policing and public administration see the move as a setback for regional development and police effectiveness. A core argument for establishing the Alta campus was to recruit and train officers locally. The theory is that individuals from the north are more likely to build careers there, as they understand the unique social fabric, vast distances, and specific challenges of Arctic policing.

"Halting intake after a single year prevents any meaningful assessment of the campus's long-term viability," said Lars Fauske, a researcher specializing in public sector geography at Nord University. "Police work in Finnmark involves distinct elements—from indigenous Sámi relations and reindeer husbandry disputes to maritime surveillance and border management—that are best understood by those with local knowledge. Training them on their home ground fosters that connection."

The Norwegian Police University College (Politihøgskolen) is the sole institution for basic police education in Norway. Its main campuses are in Oslo, Kongsvinger, and Bodø. The Alta branch was an expansion into an underserved region. Proponents argue that without a steady pipeline of locally educated officers, the Finnmark police district will remain reliant on transfers from the south, a strategy with high attrition rates.

Budgetary Pressures and National Priorities

The freeze on Alta admissions highlights the tension between national budget constraints and regional policy goals. The government must allocate funds for a fixed total number of police student places across the entire country. These allocations are influenced by national crime trends, projected retirement waves in the police force, and overarching political priorities.

In recent years, political focus has often centered on urban crime, gang violence, and cybercrime. These are pressing issues, but they can overshadow the strategic importance of securing police presence in the Arctic. The Alta decision suggests that in a tight fiscal environment, newer, smaller campuses are vulnerable. The state's investment in the physical campus and its staff is now underutilized, representing a potential inefficiency.

"This is a classic centralization-decentralization dilemma," Fauske explained. "The state wants a uniform, efficient national education system. Regions argue they need tailored solutions to meet local needs. Alta's high number of applicants proved the local need exists. The question is whether the state prioritizes cost-saving in the education budget over the potential long-term benefit of a stable, local police force in the Arctic."

The View from the North

For community leaders in Finnmark, the decision feels like a broken promise. The establishment of the academy was seen as a commitment to the region's future and a recognition of its importance to national security. The northern Norway region is central to the country's strategic interests in the Arctic, with increased military and civilian activity.

A locally anchored police force is considered integral to societal stability. Police Chief Hætta's criticism reflects this operational viewpoint. Her district needs officers who are not just physically present but culturally competent and likely to stay. The uncertainty surrounding the academy's intake creates planning difficulties for her and demoralizes potential recruits who may now look to other careers.

The situation also impacts the city of Alta. Educational institutions are key employers and attract young people. The sudden stop in student intake reduces the campus's economic and social footprint in the community before it ever had a chance to fully establish itself.

What Comes Next for Police Training in Alta?

The government's decision is for the 2026 budget only. It does not permanently close the Alta campus. Future governments could allocate funds to reopen admissions. However, the hiatus creates its own challenges. Maintaining teaching expertise and campus morale without a steady influx of new students is difficult. The gap may also lead prospective students to apply to other, more stable campuses, eroding the applicant pool for any future restart.

The Police University College leadership must now manage a campus in a holding pattern. They will be under pressure from regional stakeholders to advocate for the restoration of funds. The coming year will likely see intensified lobbying from northern politicians, police chiefs, and business leaders to secure the 2027 intake.

This case sets a precedent. It signals to other regions hoping for decentralized public sector education that even successful pilot projects are not safe from sudden budgetary cuts. The debate touches on fundamental questions about equality of public services across Norway's vast geography and how the state invests in its most remote communities.

Norway prides itself on balanced regional development. The Alta police academy was a symbol of that policy. Its current frozen state asks a tough question: is the nation's commitment to its Arctic regions strong enough to fund the institutions needed to sustain them, or will centralized budget logic consistently override local needs? The answer will shape policing in the far north for years to come.