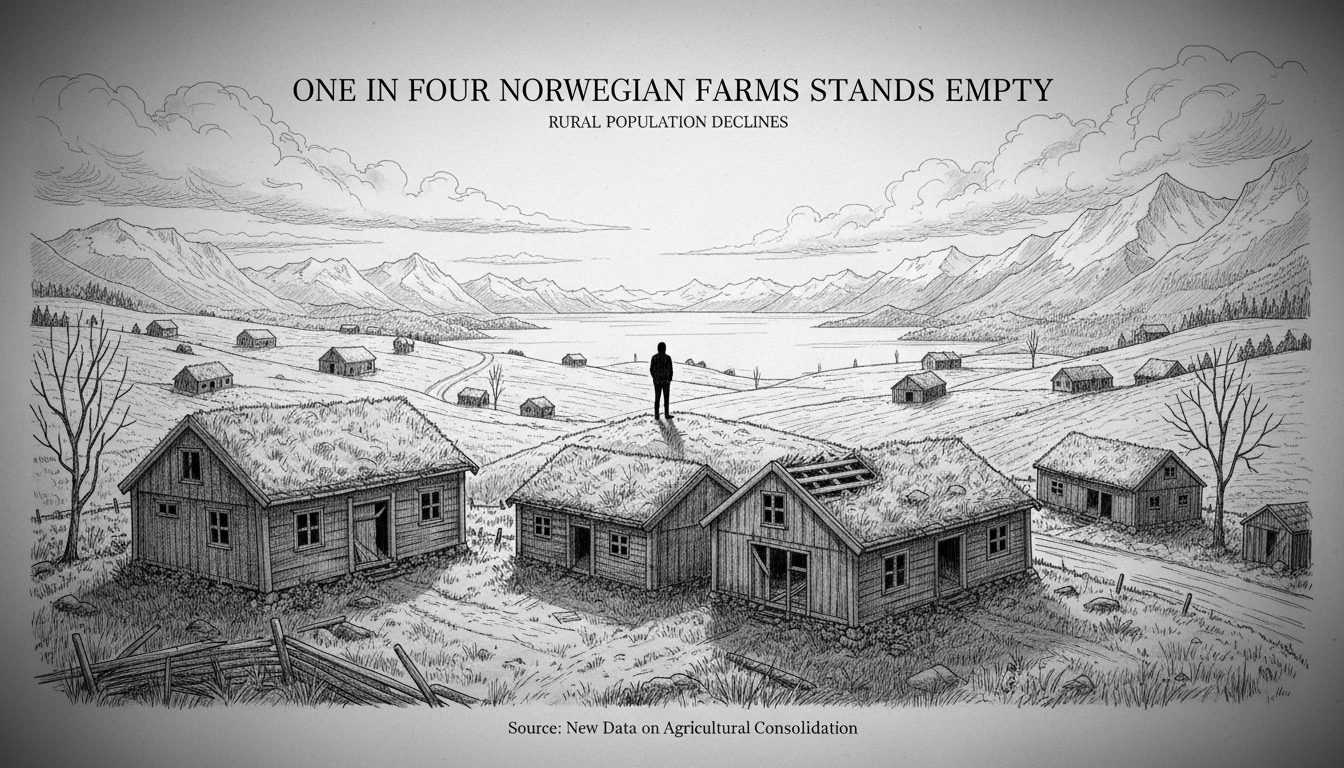

A quiet transformation is reshaping the Norwegian countryside. New data reveals nearly a quarter of all agricultural properties now stand without permanent residents. This trend highlights a deep shift in Norway's relationship with its land and raises urgent questions about the future of rural communities.

The statistics show 23 percent of all farms lack a fixed dwelling. The term 'småbruk,' meaning smallholding, is among the most searched property terms. Yet the lights remain off in thousands of farmhouse windows. Jan Erik Fløtre, leader of Vestland Farmers' Union, voices a common sentiment. He wishes there was light in more of the empty houses. He believes many people want more space, not necessarily to run a farm.

This depopulation is not a sudden change. It follows decades of agricultural consolidation. During the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, over half of Norway's farms were shut down. Since the turn of the century, nearly half of the remaining operations have disappeared. Fewer active farmers naturally mean fewer permanent residents on farmsteads.

The pattern varies dramatically across the country. Northern Norway has the highest percentage of agricultural properties with vacant residential buildings. In stark contrast, Innlandet county tops the list for occupancy. Over 16 percent of its residents live on farm properties. In Lesja municipality, that figure reaches a remarkable 48 percent.

Einar Bergsholm, a legal researcher at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences, explains the causes are complex. Some buyers purchase their childhood home to use as a holiday cabin. Another key factor is tough competition in agriculture. Farmers often need to operate two farm units to make ends meet. They can only live in one place.

The situation touches on Norway's concession laws. These laws are designed to protect multiple interests, including maintaining settlement. Their application can differ between municipalities. Bergsholm suggests a review. Making it easier to subdivide agricultural land could help. It might allow young couples who want to farm professionally to buy just the land they need. They would not have to purchase an entire, often oversized, property.

Fløtre understands that many farms are inherited within families. Only one-third of sold properties go outside the family circle. Still, he stresses the need for people in the districts to keep local communities alive. He argues it is vital that people live on farms with concessions. Managing farms without these regulated permissions is more difficult.

The empty farmhouses represent more than just statistics. They signal a challenge for Norway's policy of distributed population. Maintaining vibrant communities from the fjords to the Arctic depends on people choosing to make these places their year-round home. The data presents a clear question. Can new models of ownership and land use reverse the trend, or is this a permanent feature of modern Norwegian life?