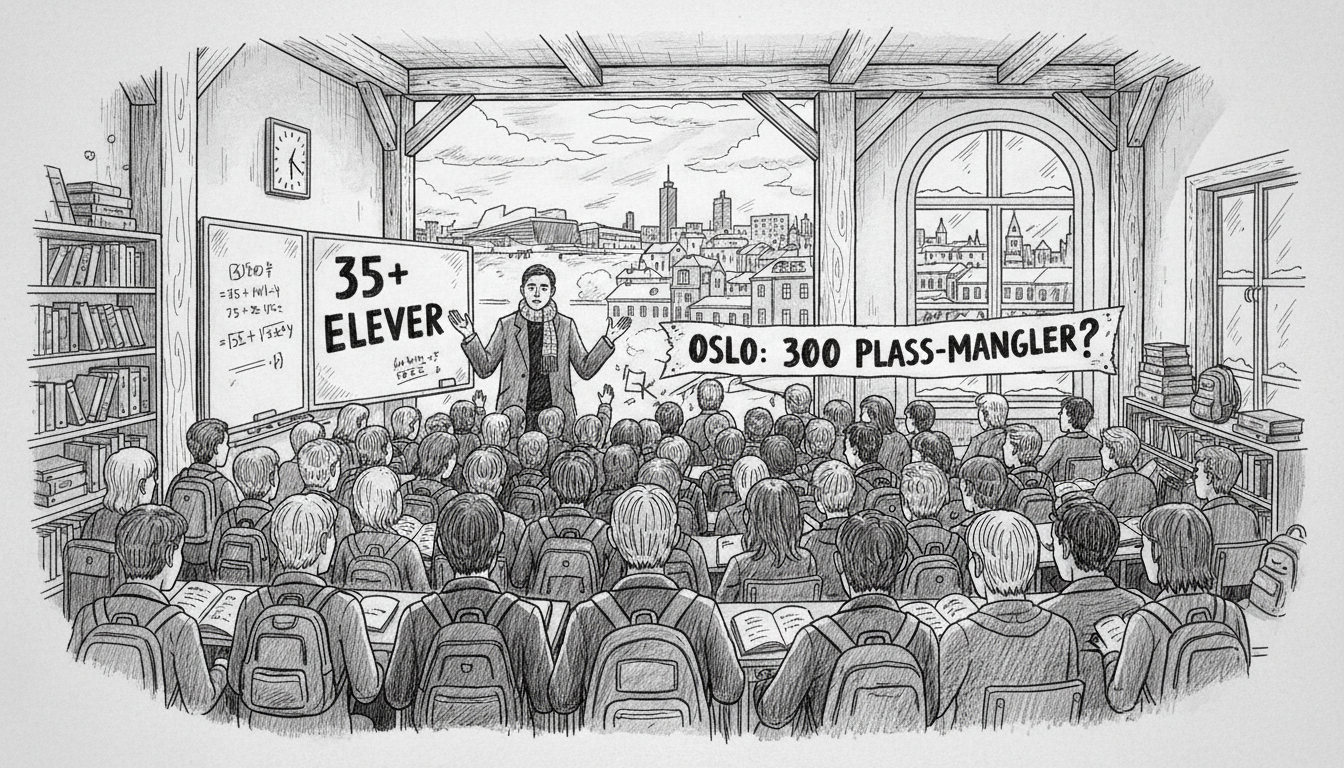

A narrow path winds through tightly packed desks at Foss High School in Oslo. Thirty-four students sit ready for their Norwegian lesson. The class will likely proceed without group activities or classroom debates. Teachers here primarily deliver lectures to manage the large class sizes.

Student Maria Zuba describes the challenges. "They don't have time to come help if you struggle with something. In some subjects, you just give up," she says.

The situation at Foss High School reflects a nationwide crisis in Norwegian education. High schools across the country, particularly in Oslo and Bergen, face severe overcrowding. Oslo's School Board now sounds the alarm about the critical situation.

Julie Remen Midtgarden, Oslo's Education Councilor, confirms that high schools are packed beyond capacity. "The capacity is completely overwhelmed. We now face an acute situation where we don't have school places for all the students who should attend high school," she states.

The city of Oslo risks violating Norway's Education Act. "Next school year, 300 students will be without school places if nothing is done," Midtgarden warns.

Norway previously maintained strict limits on class sizes—no more than 30 students in academic tracks and maximum 15 in vocational programs. Today, the only requirement is that group sizes must be "pedagogically justifiable." The trend toward larger schools and bigger classes has become evident nationwide, including in middle schools.

Thom Jambak, deputy leader of the Education Association, explains that national statistics on high school class sizes are unavailable. "But teachers give clear feedback that classes are too large in many parts of the country," he notes.

The association reports that academic track classes often exceed 35 students. A single teacher might have over 100 students during a school year. Providing quality education to everyone in such large classes becomes nearly impossible.

Teachers at Foss High School express their professional frustration. "We walk around with constant bad conscience," says Emilie Berstad Malmgren, who teaches social studies and English. The teachers painfully understand how little time they get for each individual student.

Even remembering all names presents a challenge. "Getting to know and following up each individual student is extremely demanding," Malmgren adds.

Teachers Stine Cecilie Folkestad-Øverås and Malmgren feel they cannot do their jobs properly. Many activities and teaching methods prove impossible with large classes in small rooms. Classroom debates and discussions disappear. Practical experiments and required student activities must be dropped. Oral assessments and presentations take too much time.

Having fifteen-minute subject conversations with students in groups of three takes four to five weeks for the teacher—and that's just for one class. "We only manage to have lectures. It's unjustifiable, and I feel like the focus is on quantity over quality," Folkestad-Øverås states.

The situation damages teacher motivation. "In large classes, you can get tremendous unrest, burned-out teachers, and sick leave. This isn't the recipe for recruiting to the profession," she warns.

Operating schools with classes over 30 students satisfies neither students nor staff. Students notice teachers have little time to spare. Those struggling academically or socially suffer most, according to student Maria Zuba. "Those with special needs experience being overlooked, not getting adaptations and extra tasks from teachers," she observes.

Maria Zuba, a first-year student at Foss, sees major differences between her middle school class of 28 students and her current class of 33. "In the class, we're about 20 girls. I feel it's difficult to establish a good girl environment in the class," she notes. Groups and cliques formed immediately from school start. "There becomes division because it's difficult to include everyone when there are so many."

Håkon Aleksander Bergsager's class contains 34 students. "It's cramped in the classroom and little space to walk around," he describes. Socially he thrives and enjoys meeting many people. "But it's very rare that teachers give individual follow-up in lessons. Because we are too many for them to manage it." He also misses oral assessments and subject conversations.

Maria Zuba misses more varied teaching and closer follow-up from teachers. That they almost only have written assignments creates problems, she believes. "I myself am often much stronger orally. There are many with dyslexia or ADHD at our school and in our class who would get much more out of discussions, oral tasks, classroom debate and would need subject conversations."

When students fall behind socially, keeping up becomes extra difficult. "The teachers don't have much time to help, so then it's even more important to have someone to lean on in the class."

Both Zuba and Bergsager say teachers do the best they can. Zuba believes teaching and school environment would improve significantly with smaller classes. "When I had 28 students in the class, I already felt a very big difference. Both in placement in the classroom, but also in follow-up from the teacher," Zuba recalls.

Bergsager primarily wants more physical space in the classroom. "Now we have to leave the classroom if we're going to do anything that isn't sitting at the desks," Bergsager says.

Mats Amundsen teaches mathematics, a subject many struggle with. He admits he often knows individual students aren't keeping up but simply lacks time to help them. "Is it the whole class I should prioritize, or the individual student? I can't do both," he states.

Amundsen must drop several practical experiments and activities he should do with students. Teachers say they lack sufficient time to follow up students with learning difficulties or those who become socially excluded. Meanwhile, recent years show increasing need for special education. More students receive diagnoses like autism and ADHD.

According to the Lecturer Association, education quality in classes over 30 students generally remains too poor. They also fear area standards are violated. "Politicians must give us the opportunity to give students the education they're entitled to. We don't have that today," says the Oslo county leader for the Lecturer Association.

The Lecturer Association, Education Association, and teachers interviewed agree completely on one thing: they need smaller classes to provide good teaching. The association wants a cap of 24 students for academic tracks and 15 for vocational programs.

"That would be a different world. Then we would have seen everyone, heard everyone. And we would have gotten more time and opportunity to adapt more for those with challenges like dyslexia," says Folkestad-Øverås.

Little suggests classes will shrink soon, at least in the capital. "It's difficult to fix the problem once it has occurred. This should have been solved 10-15 years ago, with planning of enough area," officials note.

Oslo's city council now faces a precarious situation. Over the last five years, high school student numbers in Oslo increased by approximately 2,600 students. Only one new school has been added. The solution has involved placing more students in existing schools.

"We overbook our schools. They take in more students than they're actually dimensioned for," says the school councilor.

Capacity remains overwhelmed, and planned new school buildings face delays, including a major school at Festningen in Oslo city center. The school councilor believes the only current solution involves changing existing schools.

Ten to fifteen years ago, the situation was opposite: child cohorts grew rapidly, requiring more elementary school places. Fagerborg High School was converted to a middle school. Nordpolen School officially opened in August 2012 as a primary and lower secondary school in former Sandaker High School premises.

Oslo municipality purchased the Festningen plot in 2017 to build a large high school. Construction still hasn't begun. The school will be ready at earliest in 2030, according to the council. Seven years have passed since Oslo municipality paid 338 million kroner for the property.

"We have schools in Oslo's school structure that have space, that have capacity," says Julie Remen Midtgarden. The schools with available space are currently primary and middle schools.

The school councilor says new schools will still be built in the city. "We have much lower student numbers in elementary school now than we had before. Then it's possible to use these buildings in a smarter way."

One proposal involves converting Møllergata Elementary School in Oslo city center to a high school. Several such changes are already planned in the latest school needs plan, which created debate this summer.

The council plans 900 new places in high school and special groups through various measures. Some primary and middle schools will also become high schools.

The Education Agency's investigation shows additional needs. The plan, however, says nothing about how many students should be in each class.

After meeting with students and staff at Foss High School, the council clearly understands that large classes don't represent a problem-free solution. "That the class size affects students' learning, that they miss education they're entitled to, that's something we must do something about," the councilor states.

This educational crisis reflects broader challenges in Norwegian urban planning and resource allocation. The concentration of population growth in major cities without corresponding infrastructure investment creates systemic pressures that affect education quality. The situation demonstrates how short-term solutions to space shortages can compromise long-term educational outcomes. As Norway continues its urban transformation, balancing physical infrastructure with pedagogical requirements remains an ongoing challenge for municipal governments.