Sweden's government wants to temporarily lower the criminal responsibility age from 15 to 13 for serious crimes. The proposal targets murder, severe bombings, and aggravated rape. Justice Minister Gunnar Strömmer argues tougher measures are needed against criminal gangs.

Multiple authorities strongly oppose the plan. The Prison and Probation Service warns that imprisoning young children could cause negative consequences. They suggest 13-year-olds should be handled through other methods.

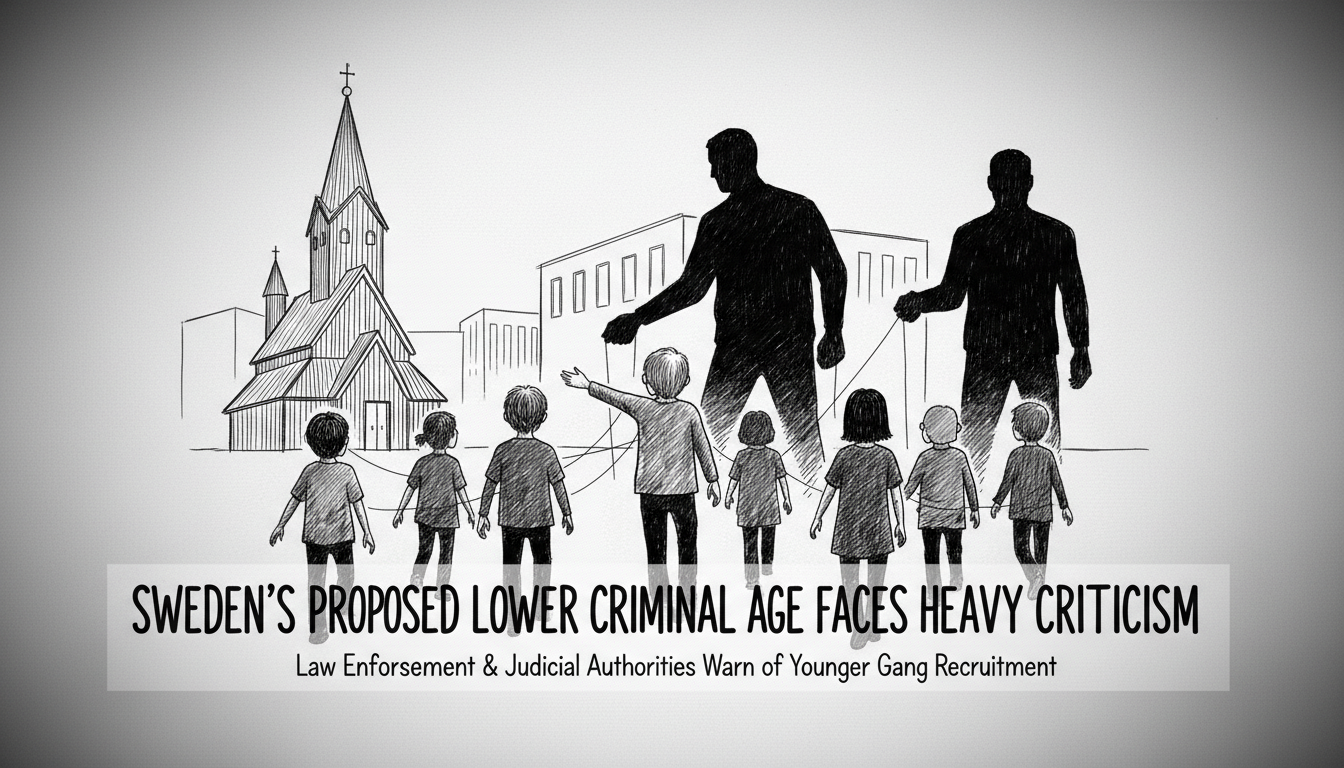

The Swedish Police Authority raises serious concerns about unintended effects. They fear criminal networks might recruit even younger children if the age drops. Instead of using 14-year-olds, gangs could exploit 11 and 12-year-olds as disposable assets in their operations.

The Prosecution Authority echoes these warnings. Officials expressed concern that crimes would simply shift to younger age groups. Criminal networks might use children who cannot be punished under current laws.

The Court of Appeal for Western Sweden suggests recent criminal policy may have already increased recruitment of younger children into serious crime. They question whether previous measures have produced the intended results.

Justice Minister Gunnar Strömmer acknowledges these concerns require serious consideration. He says the government will analyze the risk in continued work. Strömmer also notes that those ordering serious crimes seem completely indifferent to what happens to children involved.

This marks the second time the government has proposed lowering the criminal age. An earlier proposal to reduce it to 14 also faced strong criticism from referral bodies. The current temporary measure would take effect in mid-2026 if approved.

Sweden's criminal age debate reflects broader tensions in Nordic crime policy. Countries balance rehabilitation traditions against growing gang violence. The region typically maintains higher age limits than many other nations.

International readers should understand this represents a significant policy shift. Sweden has long emphasized rehabilitation over punishment for young offenders. The proposal signals growing political pressure to address organized crime more aggressively.

Legal experts note the potential international implications. Lowering the criminal age could affect Sweden's compliance with UN conventions on children's rights. The country has traditionally been a leader in juvenile justice reform.

The outcome will influence similar debates across Northern Europe. Norway and Denmark also face challenges with youth involvement in organized crime. Their governments watch Sweden's approach closely.

Parents and educators express concern about the social impact. They worry about criminalizing children who might be victims of exploitation themselves. Community organizations emphasize prevention and early intervention as alternatives.

The proposal now undergoes further analysis before parliamentary consideration. The government must balance crime prevention against child protection concerns. The final decision will shape Swedish youth justice for years to come.