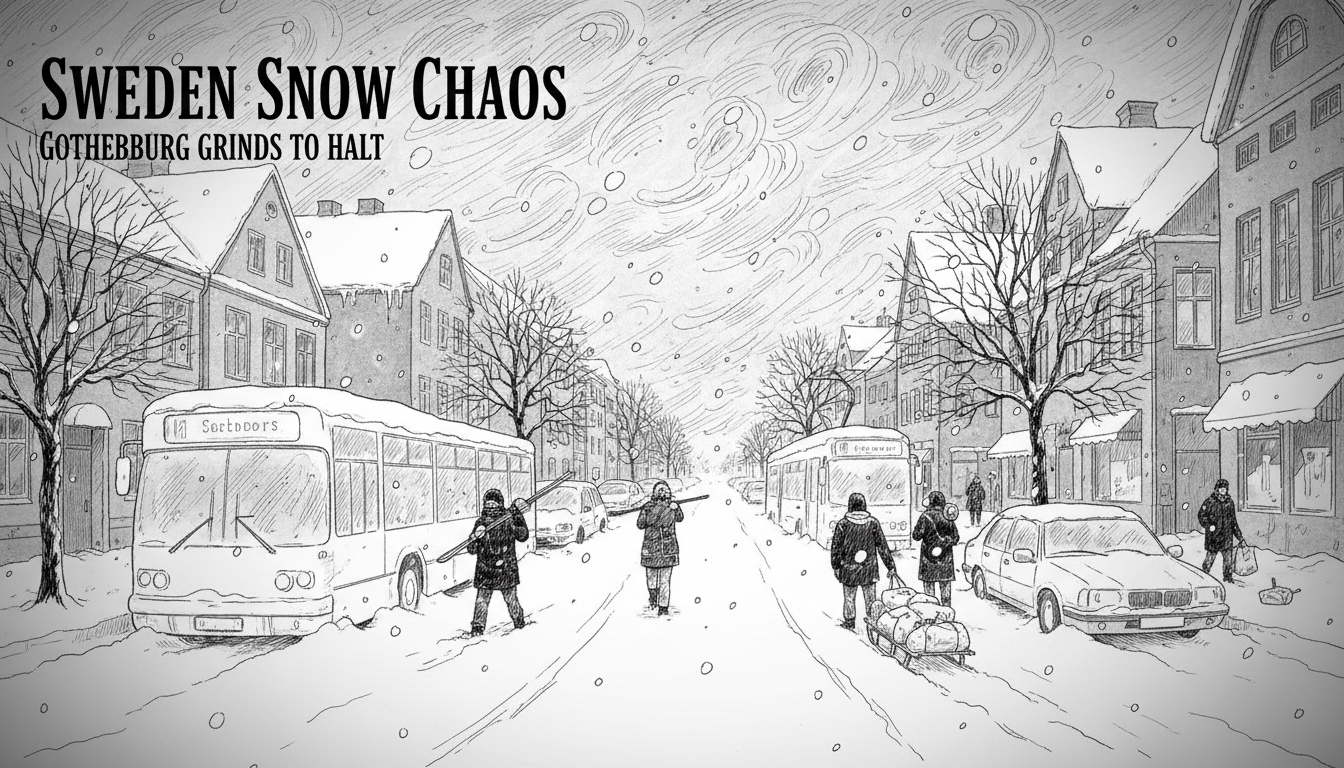

Sweden winter weather brought Gothenburg to a standstill this morning as heavy snowfall created traffic chaos across the west coast. Västtrafik delays left thousands stranded, with buses and trams stuck in deep snow. The question on everyone's lips was simple: should you even try to get to work today?

I stood at Järntorget square just after 7 AM, watching the normally bustling tram interchange fall silent. A number 11 tram sat motionless, its tracks buried under 25 centimeters of fresh powder. Commuters wrapped in thick winter jackets checked their phones with growing frustration. "I've been waiting 40 minutes," said Elias, a barista trying to get to his café in Majorna. "The app says my tram is 'delayed indefinitely.' What does that even mean?"

This scene repeated itself across Sweden's second city. The Västtrafik app lit up with red warnings as services on key routes like the 55 bus to Mölndal and the 10 tram to Guldheden were suspended. For the region's 1.7 million inhabitants, the morning routine dissolved into a slow-motion puzzle of alternative routes and cancelled plans.

The Official Response

By 8:30 AM, the city's official stance became clear. Göteborgsstad urged employers to show flexibility. "We advise people to work from home if possible," a city spokesperson said in a statement. "Our priority is clearing main arterial roads for emergency services."

The Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) had issued a yellow warning for heavy snow. But the reality on the ground exceeded many expectations. The west coast's unique climate often turns predicted snow into sleet or rain. This time, the cold air won, dumping snow that stuck immediately to wet roads.

Västtrafik's communication team worked overtime. "We're doing everything we can," their social media account posted. "Our vehicles are equipped for winter, but this amount of snow in this timeframe creates exceptional challenges." The authority advised against all non-essential travel throughout the morning rush hour.

A City Built on Different Winters

Gothenburg's relationship with snow is complicated. Unlike northern Swedish cities like Luleå or Umeå, which expect and plan for meters of snow, Gothenburg experiences a maritime climate. Winters are typically milder and wetter. This means the city's infrastructure faces different challenges when proper snowfall arrives.

"We get this maybe two or three times a winter," explained Lena Forsberg, a civil engineer who has studied urban planning in the city. "The problem isn't just the snow. It's that it often falls around zero degrees Celsius. That creates slush that freezes into ice overnight. Our fleet of plows is adequate for normal conditions, but a concentrated dump like this overwhelms the system."

Forsberg points to another factor. "Gothenburg is hilly. Neighborhoods like Haga and Linné are built on slopes. A few centimeters of snow on those cobblestone streets makes them impassable for trams and dangerous for cars, even with winter tires."

The Human Cost of a Snow Day

Beyond the transport statistics lies a more personal story. For parents, the snow created immediate childcare dilemmas as schools announced delayed openings. For hourly workers in service industries, the decision to stay home meant lost wages.

At a quiet espresso bar in Vasastan, manager Johanna Pettersson served the few customers who made it through the snow. "Two of my three staff called saying trams weren't running," she told me. "I don't blame them. I skidded twice just walking here from my apartment. We'll manage with just me today, but it's lost income for everyone."

Meanwhile, in the office towers of Lindholmen, the IT sector adapted seamlessly. "Our entire team is logging in from home," said software developer Markus Lindgren via video call. "For us, the snow is just an inconvenience. It makes you realize how unequal the impact is. If your job can't be done remotely, you're forced to risk the journey or lose pay."

This digital divide highlights a lasting change from the pandemic. Sweden's widespread adoption of remote work provided a ready-made solution for many office workers, cushioning the economic impact of the disruption.

The Preparedness Debate

Every significant snowfall in southern Sweden reignites the same debate. Is the country prepared for its own winter? The answer depends on where you live.

"There's a north-south divide in winter readiness," said Professor Anders Kjellström, a climatologist. "In the north, winter tires are mandatory from December to March. Municipalities have larger fleets of heavy plows. In Gothenburg, Malmo, and Stockholm, winters are more unpredictable. The infrastructure is designed for efficiency, not necessarily for extreme winter resilience."

He notes that climate change adds complexity. "We're seeing more of these volatile weather events. Rain turns to sudden heavy snow. This requires more dynamic response plans, not just seasonal ones."

Local politicians often face criticism after snow events. The opposition typically questions whether enough plows were deployed quickly enough. The governing coalition defends its resource allocation, noting that maintaining a massive winter fleet for a handful of days each year is economically challenging.

A Moment of Collective Pause

Despite the frustration, there's another side to these Swedish snow days. They force a pause. The blanketing white silence mutes the city's constant hum. Children, delighted by the unexpected holiday, built snowmen in parks like Slottsskogen. Some adults rediscovered the simple pleasure of walking through fresh, unmarked snow.

On social media, the tone shifted from anger to shared experience as the morning progressed. Photos of stranded trams gave way to images of cross-country skis on city streets and impromptu sledding on the slopes of Keillers Park. The Swedish concept of "mys" – a feeling of cozy contentment – emerged as people lit candles, made extra coffee, and accepted the slower pace.

By midday, the city's rumble began to return. The dedicated crews from Göteborgsstad's street and parks department made visible progress. Main thoroughfares like Kungsportsavenyn and E45 were cleared and gritted. Västtrafik announced a gradual return to service, starting with key bus routes and underground tram sections.

Looking Ahead

The snow will melt, likely within days as milder Atlantic air returns. The tracks will be cleared, and the routines restored. But today's chaos leaves behind questions that Sweden will grapple with for seasons to come.

How does a modern city balance efficiency with resilience? Can public transport adapt to increasingly unpredictable weather patterns? And in a society that values punctuality and reliability, how do we redefine productivity when nature intervenes?

For now, the people of Gothenburg are doing what Swedes have always done in winter: adapting, enduring, and finding a way forward. Some are still working from their kitchen tables. Others are finally boarding a crowded tram, shaking snow from their boots. The city keeps moving, just at winter's pace.

Tonight, SMHI forecasts temperatures dropping to minus five. The slush will freeze into sheets of black ice. The real test for Gothenburg's winter readiness may come not with the falling snow, but with what it leaves behind.