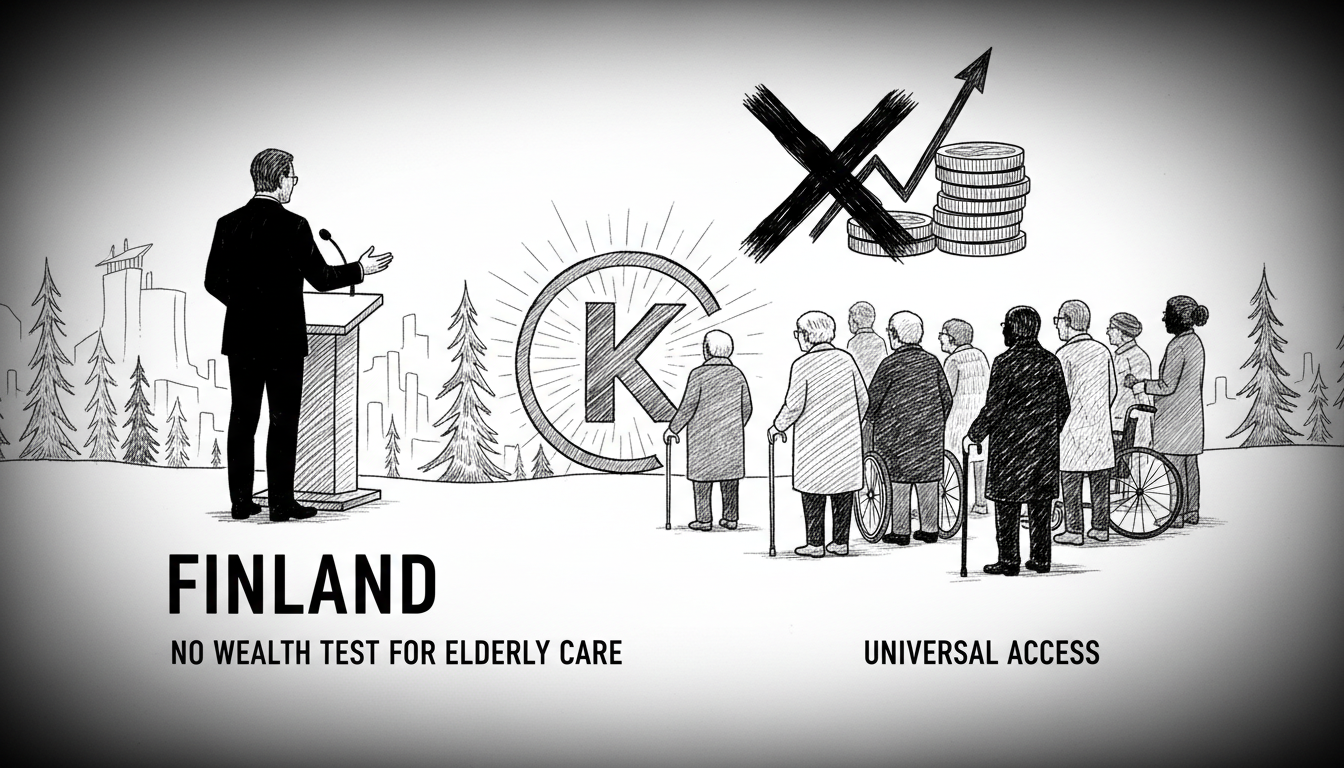

Finnish Social Affairs and Health Minister Kaisa Juuso has firmly rejected proposals to include personal wealth in calculating fees for public round-the-clock elderly care. The minister's comments follow a new analysis from the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, which examined the potential fiscal and social impacts of such a policy shift. Currently, care fees in Finland's public sector are based solely on a client's income, a system designed to ensure universal access to essential services regardless of financial background.

The institute's study proposed considering assets like stocks, funds, and investment properties in the fee calculation. This change would affect approximately fourteen percent of long-term care residents. For half of those impacted, monthly fees would rise by a maximum of 380 euros. However, the average increase could reach 830 euros per month, representing a substantial financial burden for affected seniors and their families. Minister Juuso, a member of the Finns Party, addressed the report during a parliamentary session in Helsinki, stating the government is not prepared to adopt the proposal.

Juuso argued that Finnish citizens already pay high taxes and deserve equal access to services. She emphasized the need for stronger political deliberation before any policy direction could be set. The minister confirmed the current government has no plans to investigate wealth-based fees during its term. This stance places the government at odds with technocratic recommendations aimed at addressing Finland's long-term public finance sustainability, particularly as the population ages and care costs rise.

The existing fee structure is complex. For single individuals, the client fee is eighty-five percent of net income after deducting prescription medicine co-payments and rent. If a spouse's income and assets are considered, the share drops to forty-two point five percent of the couple's combined net income. Regulations mandate that a minimum of 183 euros must remain after all deductions for personal use, a safeguard for basic living expenses. The institute stressed its report provides background information for debate without taking a position for or against the change.

This debate touches a core principle of the Nordic welfare model: the balance between universalism and means-testing. Finland, like its neighbors, has historically championed services based on need, not wealth. Introducing asset tests for elderly care represents a philosophical shift that could redefine the social contract. The discussion occurs against a backdrop of strained municipal finances and difficult choices about the future funding of welfare services. The minister's swift dismissal suggests the political appetite for such a fundamental change is currently low, prioritizing the principle of equal treatment over potential revenue gains. The issue is likely to resurface as demographic pressures intensify, forcing future governments to revisit the balance between fairness, sustainability, and the rights of citizens who have saved and invested throughout their lives.