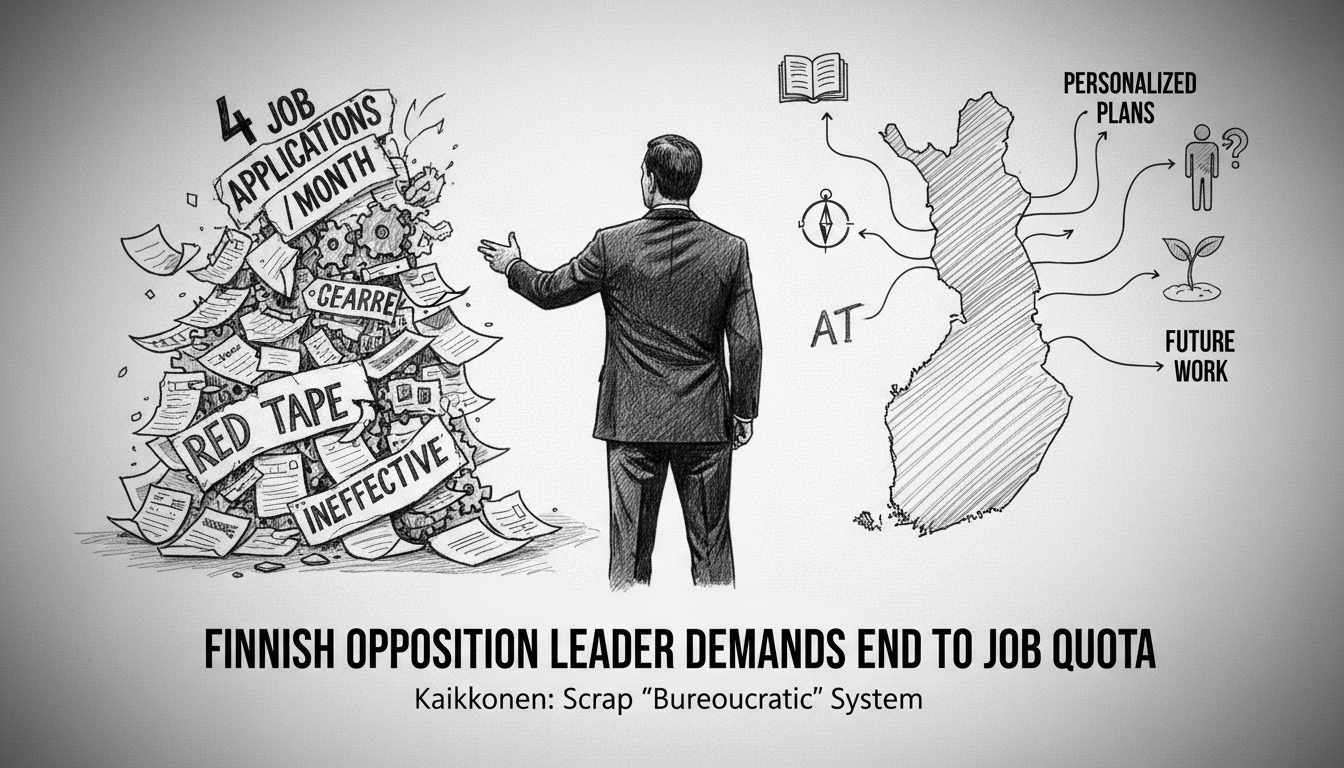

Finnish opposition leader Antti Kaikkonen has launched a sharp critique of the country's unemployment system, demanding the abolition of a key rule. The Centre Party chair and Member of Parliament argues the current model, which mandates jobseekers submit four applications per month, has become counterproductive. Kaikkonen states the system now functions as a mechanical and bureaucratic exercise that fails to promote actual employment in a period of high unemployment. His proposal represents a significant policy challenge to the current government's approach to labor market activation.

Kaikkonen told a major Finnish newspaper that the four-application requirement guides people to apply for the sake of quantity, not for genuine employment prospects. He notes employers are simultaneously burdened by floods of applications. Criticism rains down on this model from the unemployed, employers, and the public employment offices themselves, he said. This does not serve anyone, Kaikkonen concluded. He argues that time in employment offices is spent on monitoring and logging when it should focus on personal meetings, guidance, and cooperation with employers.

The Centre Party leader proposes replacing the quota model with a new system based on a jobseeker's personal employment plan. This individualized plan could include job searching, studying, updating skills, entrepreneurship, or strengthening work capacity. The content would depend on what genuinely supports employment for that person. People are in different life situations, Kaikkonen noted. An individual plan provides an opportunity to progress in a way that is realistic and effective. In his model, activity would be assessed periodically together with an expert. This would reduce the use of punishments and automatic sanctions and restore trust to the system.

Kaikkonen stresses the job search system must support employment, not complicate it. The current model should be frankly blown up and replaced with a better one, he said in his statement. The system must work for people, not people for the system. We must move to a model that intensifies guidance and the strengthening of skills. That is also in the employers' interest. He argues the new model would be flexible, up-to-date, and better at responding to changes in the labor market. Finland needs a system that measures progress and goals, not the number of applications, Kaikkonen asserted. The time for this change is now.

This policy push sits within a broader Nordic debate on active labor market policies. Finland's system, like those in Sweden and Denmark, has long emphasized activation to reduce long-term unemployment. The four-application rule was designed to ensure jobseekers remained engaged. Critics, however, have argued for years that it creates perverse incentives and administrative bloat. Kaikkonen's intervention signals a potential shift towards a more personalized, service-oriented approach championed by some other EU nations. The proposal will likely face scrutiny from the governing coalition, which must balance budget constraints with social policy effectiveness. For international observers, the debate highlights Finland's ongoing struggle to modernize its famed welfare state structures in the face of economic and demographic pressures. The outcome could influence similar discussions across the Nordic region regarding how to best support citizens in transitioning to meaningful work without excessive bureaucracy.