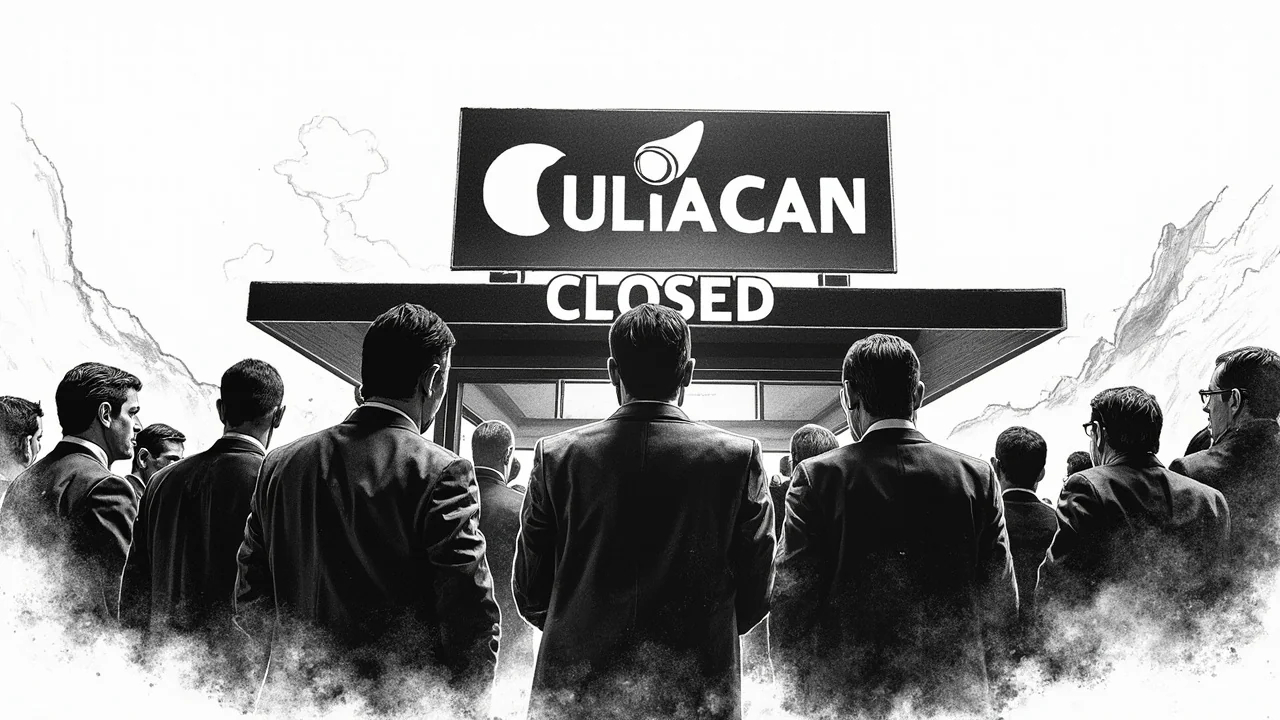

Iceland's long-running Mexican restaurant Culiacan has been declared bankrupt with nearly 119 million ISK in claims left unpaid. The final notice was published in the Legal Gazette on January 16th, confirming the Reykjavík District Court's September 2024 bankruptcy ruling. No assets were found in the estate, and proceedings concluded on November 26th with no payment to creditors. The listed claims total 118,783,101 Icelandic krónur.

The Final Accounting

The bankruptcy estate of Taco Taco ehf., the company behind Culiacan, has been officially dissolved. The court's ruling from last autumn led to a swift liquidation process. Creditors, which likely included suppliers, tax authorities, and landlords, received nothing. The restaurant's location on Suðurlandsbraut, a major road in the Reykjavik capital area, closed its doors for good in October 2024. This closure marked the end of a 21-year presence in the Icelandic dining scene, a significant run in a competitive and costly market.

A Two-Decade Run Ends

Culiacan first opened its doors in July 2003 in the Faxafen area of Reykjavik. It later moved to its final and most prominent location at Suðurlandsbraut 4 in 2010. The chain attempted to expand its footprint, operating briefly in the Hlíðasmári commercial area in Kópavogur and later opening an outlet in the popular Mathöll Höfða food hall in 2018. The Höfði location, situated in a bustling district known for its mix of offices and retail, represented an attempt to capture the lunch and casual dining crowd. The failure to sustain these operations points to the intense pressure on mid-range eateries facing rising operational costs, from wages to ingredients, in the greater Reykjavik area.

The Reykjavik Restaurant Landscape

The collapse of a established brand like Culiacan sends a ripple through Reykjavik's service industry. It highlights the precarious financial margins many restaurants operate on, even those with longevity and name recognition. The capital's dining scene has seen rapid transformation, with a surge in new openings often funded by tourism-driven boom years. As tourism numbers fluctuate and local consumer spending is squeezed by persistent inflation, older concepts can struggle to adapt. The location on Suðurlandsbraut, while busy with car traffic, may have suffered from shifting consumer patterns favoring walkable districts like Grandi, the city center, or the evolving Hafnarfjörður waterfront.

Legal Process and Creditor Reality

The bankruptcy follows a standard Icelandic legal procedure. After a company is declared bankrupt, a district court-appointed liquidator takes control of the estate to identify and sell any assets. The proceeds are then used to pay creditors in a legally mandated order of priority, with secured creditors first in line. In this case, the liquidator's investigation found no assets of value to seize and sell. This outcome, known as a "null estate" bankruptcy, is a worst-case scenario for unsecured creditors. They bear the total loss, receiving zero ISK on the króna owed. For small local suppliers, such a loss can be devastating.

Industry Pressures and the Future

The story of Culiacan's bankruptcy is more than a single business failure. It is a data point in the economic environment for Icelandic hospitality. Restaurant operators consistently cite high rents, steep energy costs despite geothermal advantages, escalating food prices, and a tight labor market as critical challenges. While fine dining and unique experiential concepts may still attract tourists, the middle ground occupied by family-friendly or casual weeknight dinner spots is becoming increasingly risky. The closure eliminates jobs and reduces consumer choice, but it also free up a commercial space in a prime location. Its future use will be a telling indicator of what type of business landlords believe can succeed there now.

A Community Farewell

For many Icelanders, Culiacan was a fixture. Over two decades, it served as a regular spot for family dinners, casual meet-ups, and a taste of something different in a city once dominated by simpler fare. Its closure, especially following the shuttering of its food hall outlet, was noticed. Online forums and social media saw locals sharing memories of meals there, marking its passage from novelty to institution to casualty. The human impact extends beyond nostalgia to the staff and managers who lost their livelihoods. In a small labor market, their search for new positions in the sector will add to the competitive pressure for remaining restaurant jobs across the capital region.

What Comes Next?

The empty unit on Suðurlandsbraut now stands as a quiet testament to a shifting economy. Will another restaurant take the risk, or will the space be converted for retail, offices, or a different service entirely? The bankruptcy of Taco Taco ehf. is a closed legal case, but its implications for Iceland's crowded restaurant sector remain open. It underscores a simple, harsh reality: longevity is no guarantee of survival when fixed costs climb and consumer habits change. As Reykjavik continues to evolve, how many other familiar names might face a similar final notice in the Legal Gazette?