A small lamp in a Kristiansand living room holds a quiet rebellion against planned obsolescence. Its Osram bulb has glowed continuously since 1921, outlasting generations of newer technology. This story of endurance offers a surprising lens on modern innovation and product design.

Frode Haga Olsen inherited the lamp from his grandmother. He says the light has become part of his soul. The bulb is a rare 'glimlampe' or glow lamp. It differs from traditional incandescent bulbs. It uses a small gas-filled chamber under low pressure. This design consumes minimal electricity. The lamp has only gone dark during two household moves and occasional local power cuts.

Osram developed its first light bulb in 1906. The brand is now managed by Ledvance. Company representative Trond Sandstrøm calls the Kristiansand lamp a treasure. He says such century-old bulbs are rare. Stories like this spread joy in the office. He notes the world's oldest functioning bulb is the Centennial Light in California. It has shone since 1901.

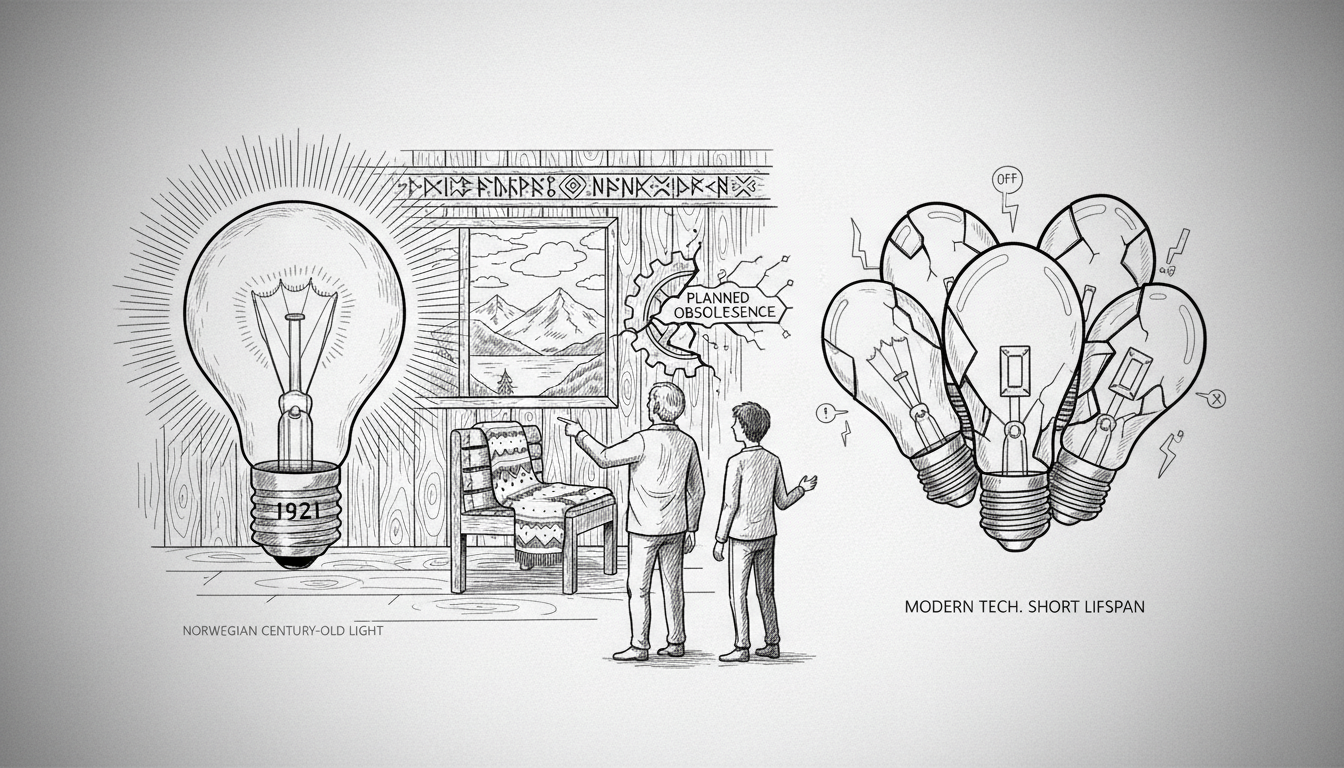

This longevity poses questions for today's tech-driven Oslo innovation news. Norwegian tech startups often focus on rapid iteration. The bulb represents a different philosophy. It values durability and simplicity over constant upgrades. This contrast is central to discussions on Norway digital transformation and sustainable design.

Chief researcher Ole Martin Løvvik at SINTEF works on sustainable energy technology. He laughs when hearing about the persistent lamp. He calls it fantastic. Modern LED bulbs on the consumer market cannot match this lifespan, he explains. Traditional incandescent bulbs fail when their filament breaks. LED technology degrades differently. Materials within the LED wear out over time. This causes gradual dimming. Sometimes the transformer fails completely.

Løvvik states a key point. Consumer LED lights are not designed for maximum lifespan. They are engineered to compete with the generation they replaced. They must last long enough to be a viable alternative to old incandescent bulbs. They achieve this, even at a higher price point. But they are not optimized to last a century. This reflects a broader Scandinavian tech hub trend. Products balance performance, cost, and market competition rather than pure endurance.

Sandstrøm was once offered a pallet of new bulbs in exchange for the antique. He refused. He believes the lamp should be passed to the next generation. It should be left to shine as long as it can. He sees it as a small light for the future. A symbol that some things can almost last forever.

For Olsen, the ritual is simple. Almost every morning he glances at the corner. He checks to see if it still glows. He admits a low mood would follow if it ever goes dark. The bulb provides more comfort than illumination. It shines like a small sun, he says. But it gives little practical light. It serves more as decoration or a cozy presence.

This narrative connects to Nordic technology trends emphasizing sustainability and quality. It challenges the disposable nature of modern electronics. In a region celebrated for its Oslo tech districts and innovation labs, a 100-year-old bulb offers a silent lesson. True innovation might sometimes mean building things that simply work, and keep working, far beyond any expected timeline. It is a story not just about light, but about time, memory, and the value of things that endure.