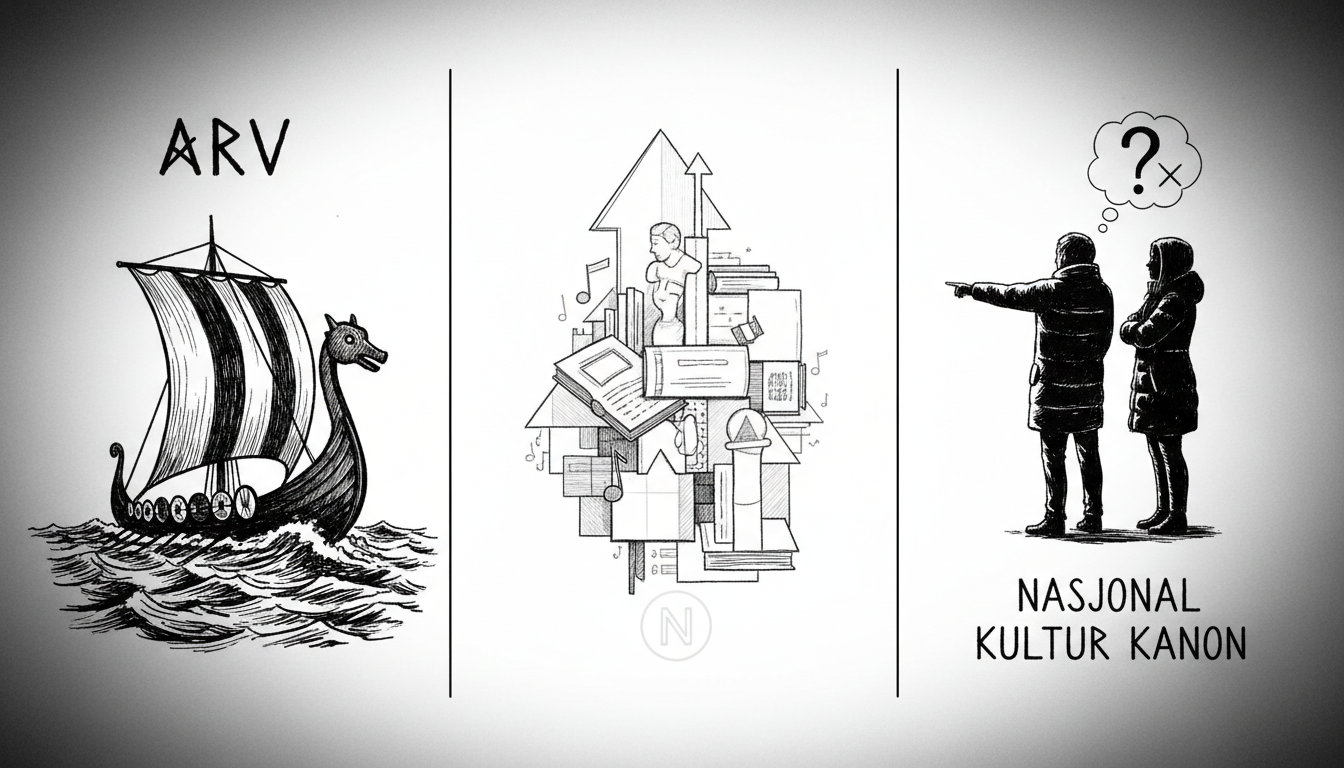

A major political debate has ignited in Norway over the creation of a national culture canon. The proposal, championed by the Conservative Party, aims to define a list of the country's most essential works of art, music, literature, and architecture. This initiative seeks to establish a common cultural reference point in an era of perceived social division.

Conservative MP Haagen Poppe is leading the charge. He argues a canon would act as a guide to Norway's cultural heritage. It would help both native citizens and newcomers understand national identity. The list would include works from classical composers like Edvard Grieg to modern pop acts like A-ha. Poppe insists the project is not culturally conservative. He says it must include vital contributions from working-class culture and artists with diverse political views.

The proposal has reportedly gained enough support from culturally conservative factions within the Christian Democratic Party and the Centre Party to achieve a parliamentary majority. This marks a shift from past attempts. The Progress Party proposed a similar measure in 2006 but found no allies. A 2017 effort by a Conservative minister was surprisingly voted down by the party's own national convention.

Culture Minister Lubna Jaffery of the Labour Party strongly opposes the plan. In a written response to parliament, she called the initiative 'particularly misguided'. Jaffery stated the government's cultural policy must uphold core values like democracy, free speech, and inclusive community. She believes a top-down canon is not the way to achieve these goals. The minister raised three main objections. She criticized the proposal's understanding of culture as something static. She highlighted the economic cost and bureaucracy involved, citing Sweden's similar process which cost 8 million Swedish kronor. Jaffery also warned such a list could become exclusionary and create hierarchical boundaries between cultural expressions.

The debate mirrors experiences in other Nordic nations. Sweden finalized its own culture canon earlier this year after a process initiated by right-wing parties. It faced criticism for being elitist and overlooking working-class culture. Denmark established its canon in 2006. Proponents in Norway argue the very process of public debate has value, regardless of the final list. They envision a selection made by an independent committee of experts, not politicians, possibly appointed by the Norwegian Cultural Council. The public would be invited to contribute, following the Swedish model which generated over ten thousand public submissions.

At its core, this is a conflict between two visions of national identity. One side sees a defined canon as an anchor in a fast-changing, digital world where common reference points are vanishing. The other side views it as a state-sanctioned hierarchy that could stifle diversity and the organic, continuous evolution of culture. The political reality suggests a parliamentary vote could happen, setting the stage for a significant and potentially expensive national project that will define how Norway talks about its cultural soul for decades to come.