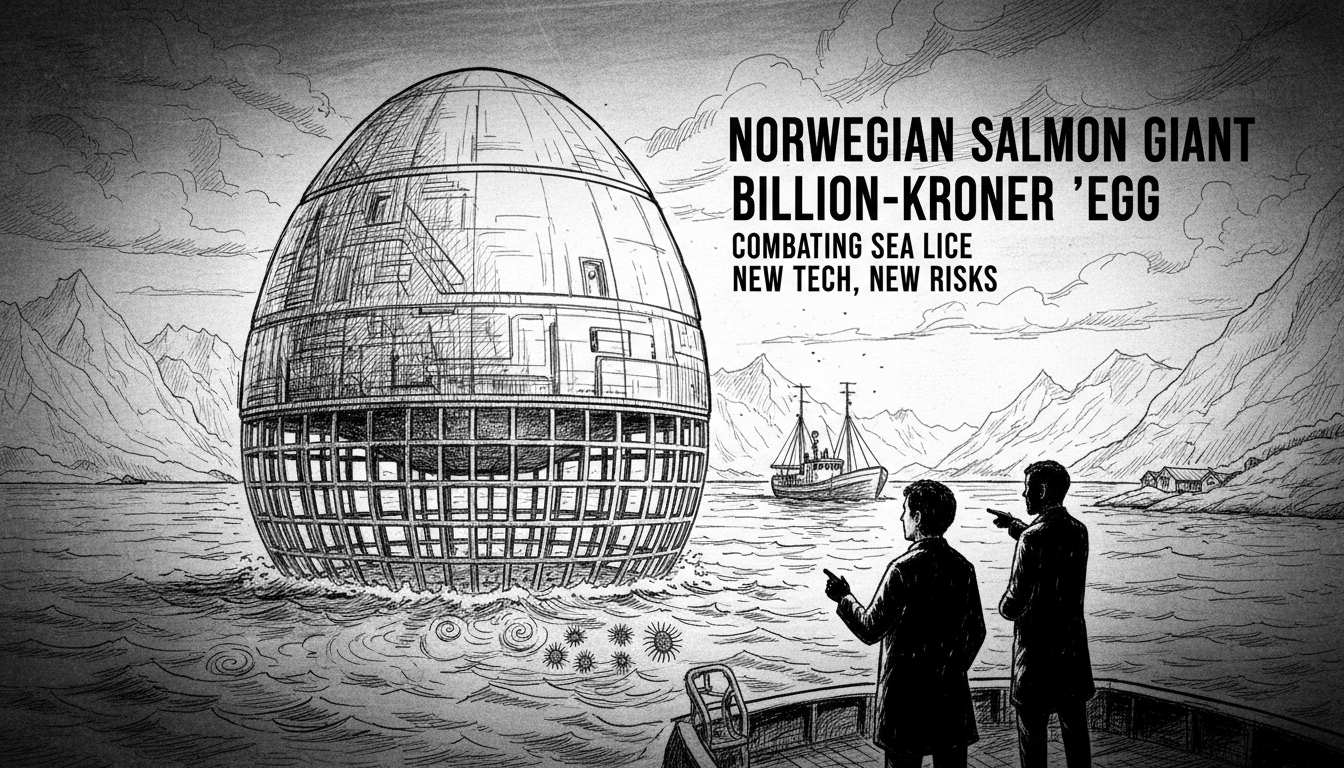

A Norwegian aquaculture company is betting nearly one billion kroner on a floating egg-shaped tank. The goal is to solve the industry's persistent sea lice problem. The massive structure is now anchored in a northern fjord after a two-week journey from Turkey.

Nordlaks, the company behind the project, calls it the 'Storbåtsegget' or 'Large Boat Egg'. It measures 78 meters in diameter and rises about 50 meters from its deepest point. The tank can hold over 3,000 tons of salmon. It is open at the bottom but sealed down to 20 meters below the surface.

The theory is simple. Sea lice concentrate in the upper water layers. By blocking surface water intake, the system should drastically reduce lice infestation. Fixed paddles along the lower structure capture ocean currents. They guide fresh water into the tank to ensure circulation.

Project leader Bjarne Johansen explained the concept. 'The concentration of lice is much higher in the upper water layers. If you stop water inflow at the surface, you reduce the supply of salmon lice,' he said.

Founder Inge Berg acknowledged the project's high cost and delays. 'Things have become terribly expensive, and construction costs are rising sharply. Unfortunately, it has taken too long and cost too much,' Berg stated. The price tag is approaching one billion Norwegian kroner.

Despite the expense, the project carries significant potential financial upside. It operates under a special government scheme called 'development permits'. These permits encourage companies to test new, costly technology that can solve environmental challenges.

The deal works as a carrot. The state allows Nordlaks to test the concept with a large biomass. If the 'egg' works as planned, these temporary permits can convert to permanent, ordinary farming licenses for a fee. In a market where standard salmon quotas cost hundreds of millions, this conversion represents enormous value.

'It means that even though the construction has been expensive, Nordlaks secures future production rights at a fraction of the market price,' an industry analyst noted. This model is a key part of Norway's strategy to push its aquaculture sector toward more sustainable, closed-containment systems.

However, researchers warn of new risks. Frode Oppedal from the Institute of Marine Research studies fish welfare in farming facilities. He points out that closed systems solve some problems but create others.

Oppedal highlights jellyfish as a hypothetical example. In open pens, jellyfish partially enter or drift through a limited area. In a closed system with water intake, the risk is different. 'If you get a jellyfish into the intake here, it gets ground up into tiny burning particles. They spread around and circulate in the entire closed pen, and suddenly all the fish can be destroyed,' Oppedal explained.

He also stressed the system's vulnerability. While salmon today get fresh water for free from nature, the 'egg' depends on technology. 'When you close the fish in, you have much more responsibility. There is more you must control, and then the risk increases that something can go wrong. If the power goes out or pumps fail, the fish get neither oxygen nor new water,' the researcher said.

The first fish will move into the tank in the spring. Only then will Nordlaks learn if the giant investment actually produces healthier salmon. The company remains cautious in its promises.

'We see this as a development project to learn. It is not a revolution for the industry, but a step in the gradual development,' said Inge Berg of Nordlaks.

Oppedal agrees. He does not believe closed systems at sea will fully replace today's open-net farming. 'You cannot replace the advantages of open pens, where enormous amounts of water flow right through,' he said. He suggests the technology might end up as a kind of 'kindergarten' for salmon in an early phase, protecting small fish before they are transferred to open pens.

The project underscores a major trend in Norwegian tech and aquaculture. Oslo's innovation districts are fostering similar hybrid solutions that blend marine biology with engineering. This 'egg' represents a tangible outcome of Norway's push for digital and biological transformation in its traditional industries. Its success or failure will influence future funding for similar Nordic technology ventures aimed at solving environmental challenges through engineering.