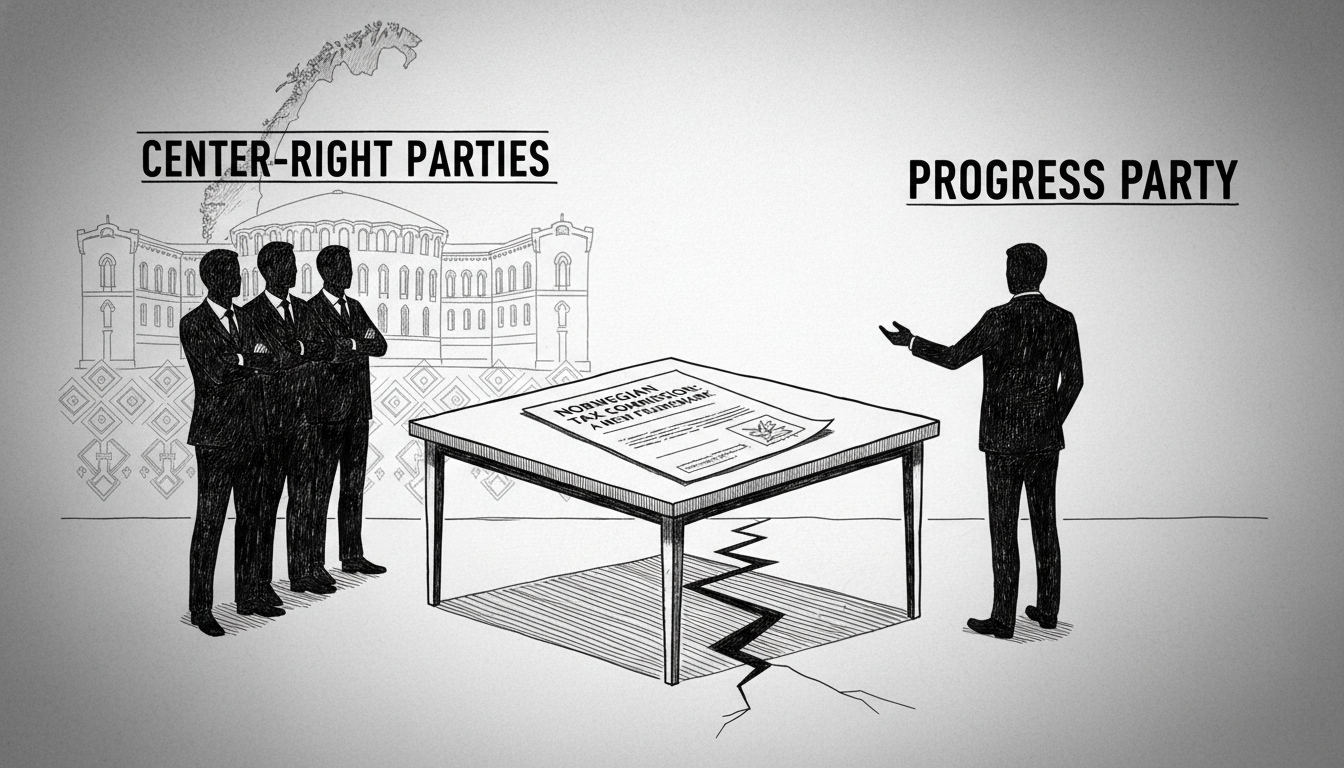

A major push by Finance Minister Jens Stoltenberg to establish a broad parliamentary tax commission has secured critical backing from three center-right opposition parties. The Conservative Party (Høyre), the Christian Democratic Party (KrF), and the Liberal Party (Venstre) have accepted the invitation to participate. The far-right Progress Party (Frp) has firmly declined, creating a clear political fault line. This development marks a significant shift from earlier this year when Stoltenberg's initial proposal was rejected by nearly all parties. The commission's mandate is to forge a lasting, cross-party tax agreement within the Storting, Norway's parliament, aiming to provide long-term predictability for the Norwegian economy.

For the Conservative Party, participation hinged on securing a mandate focused on business competitiveness. 'It has been absolutely necessary for Høyre that the commission will provide recommendations that help Norwegian business achieve a competitive tax level. Now that we have secured this, we can support a commission,' said the party's finance spokesperson, Nikolai Astrup. This reflects a core concern for Norway's key industries, including the oil and gas sector centered in the North Sea and the Norwegian Sea, and maritime operations along the western fjords. A stable tax framework is seen as vital for investment decisions in projects from the Johan Sverdrup field to future Arctic developments.

The Progress Party's rejection was unequivocal. 'We will not participate in throwing dust in the eyes of the voters,' stated deputy leader Hans Andreas Limi. He argued that a consensus spanning from the left-wing Red Party to Frp is impossible. Instead, Frp presented the government with a binary choice: pursue tax increases with left-wing parties or implement tax cuts with Frp. Finance Minister Stoltenberg expressed disappointment, stating that Frp's refusal to 'take responsibility' deprives the business community of needed stability in an increasingly fragmented political landscape.

Other parties emphasized the broader economic benefits of an agreement. The Christian Democrats' finance spokesperson, Jørgen H. Kristiansen, stated their goal is for families and businesses to retain more of their income. The Liberal Party's Abid Raja stressed that a broad compromise is the only way to create a tax system that gives companies the security to invest and grow. The Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise (NHO) welcomed the compromise on the commission's mandate, with chief Ole Erik Almlid noting it could pave the way for substantial reductions in corporate capital gains tax, a key demand from the business sector.

The formation of this commission is more than a procedural step. It represents an attempt to insulate Norway's economic policy from short-term political cycles, especially as debates over wealth distribution, green energy transitions, and Arctic sovereignty intensify. The success or failure of this effort will directly impact Norway's sovereign wealth fund, the world's largest, and the fiscal room available for future governments. With Frp outside the process, the potential for a truly durable 'broad agreement' is now in question, setting the stage for difficult negotiations in the Storting building in Oslo.