A recent parliamentary inquiry has exposed a significant gap in Sweden's nuclear energy oversight. Swedish nuclear power plants face no legal requirement to disclose the origin of their uranium. This voluntary reporting standard, set by the Radiation Safety Authority, has become a focal point for political debate. Five of the eight parties in the Swedish Parliament now advocate for mandatory origin labeling for nuclear fuel. This push reflects growing security concerns within the Riksdag about energy independence and supply chain transparency. The debate centers on whether current government policy Sweden provides adequate safeguards against indirect support for sanctioned entities through complex corporate ownership structures.

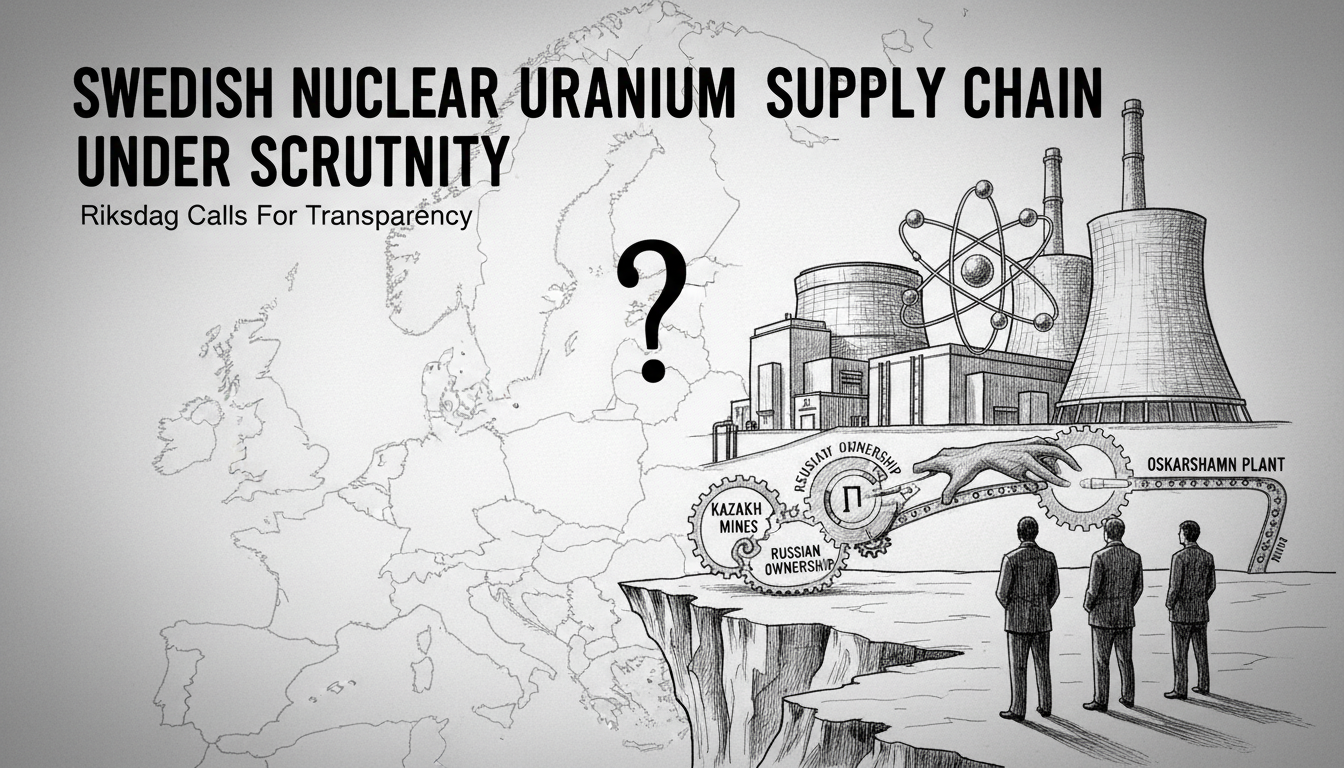

The inquiry revealed divergent practices among Sweden's major nuclear operators. State-owned Vattenfall, which operates the Ringhals and Forsmark plants, stated it sources uranium exclusively from Canada and Australia. The company provided documentation to support this claim. In contrast, Uniper, the operator of the Oskarshamn nuclear power plant, presented a more complex supply chain. The company initially stated it 'accepts' uranium from several countries, including Kazakhstan. Approximately one-fifth of Kazakh uranium production is owned by the Russian state corporation Rosatom and its subsidiaries, according to the inquiry's findings.

When pressed on whether it purchases uranium from Russian-owned mines in Kazakhstan, Uniper declined to answer multiple times. Company press spokesperson Désirée Liljevall stated they had no further information to provide. Uniper later published a statement on its website referencing a contract with the European company Urenco, which enriches uranium before it reaches Oskarshamn. The statement claimed the contract specifies that uranium is not purchased from Russia or Russian-owned companies. It acknowledged Russian ownership in some Kazakh mines but asserted Urenco only buys from sections without Russian ownership.

This explanation was immediately contested. Urenco's communications head, Nic Brunetti, clarified that his company does not purchase uranium. 'We provide the enrichment step in the fuel cycle,' Brunetti said. 'The customers, meaning the utility companies or nuclear operators, choose which actors they procure the various steps from.' This statement shifts responsibility back to Uniper for its procurement decisions. When contacted again, Uniper's press chief offered no further comment, directing inquiries to the published statement on their news platform. The refusal to elaborate on the timing of their disclosure about Russian-owned companies in Kazakhstan has fueled further scrutiny.

This situation highlights a critical vulnerability in Swedish energy policy. The absence of mandatory disclosure creates opacity in a sector with profound national security implications. Riksdag decisions on this matter could reshape procurement rules for critical infrastructure. The debate unfolding in Stockholm politics is not merely technical. It touches on fundamental questions of accountability for state-supported energy operators. The government's response will signal its commitment to aligning energy procurement with broader foreign and security policy objectives. Analysts note that without binding rules, voluntary standards rely entirely on corporate discretion, a risky proposition for strategic assets.

The implications extend beyond a single power plant. Sweden's three nuclear facilities provide a substantial portion of the nation's electricity. Ensuring their fuel supply is both secure and ethically sourced is a complex logistical and diplomatic challenge. The current framework, established by the Radiation Safety Authority, predates the current geopolitical landscape. Reform would likely require new legislation debated in the Riksdag building, potentially affecting all operators. For international observers, this case demonstrates how global supply chain issues manifest in the Nordic energy sector. It also shows the limitations of corporate self-regulation in highly politicized industries. The coming months will test the Swedish government's ability to close this regulatory gap and enforce greater transparency in its strategic energy partnerships.