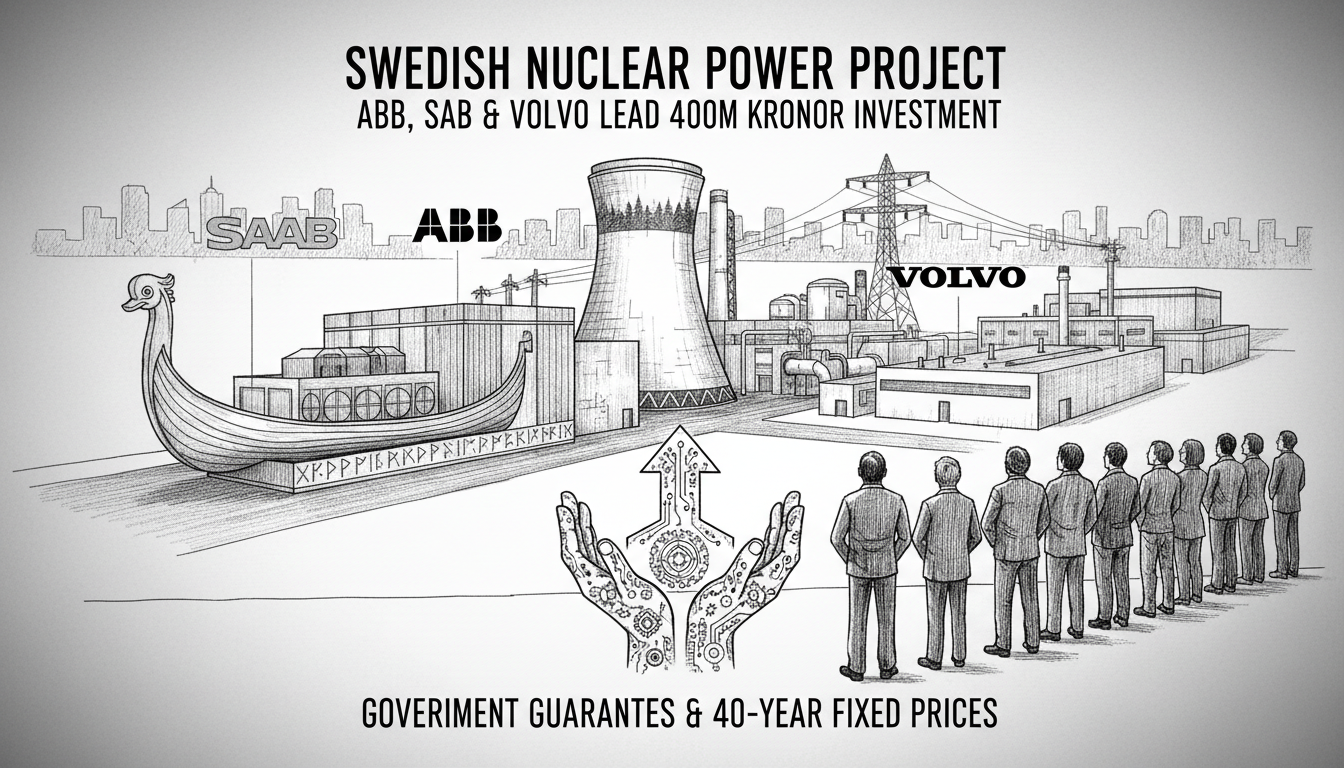

Nine major Swedish industrial companies are investing in Vattenfall's nuclear power project at Ringhals. The companies are joining the initiative under specific conditions that include substantial government support through state loans and a fixed electricity price guaranteed for 40 years.

Swedish industry is committing 400 million Swedish kronor to Vattenfall's project to build small modular reactors, known as SMRs, at Ringhals on the Värö Peninsula in Halland. This represents one of the largest private investments in Swedish nuclear energy in recent decades.

The investment comes through the Industrikraft initiative and includes nine of its members: ABB, Alfa Laval, Boliden, Hitachi Energy, Höganäs AB, SSAB, Saab, Stora Enso, and the Volvo Group. These companies span multiple sectors including manufacturing, energy, and automotive industries.

This move signals a major shift in Sweden's energy strategy. The country previously planned to phase out nuclear power but has reversed course amid energy security concerns and climate goals. The guaranteed electricity price provides stability for both the energy producers and industrial consumers in an uncertain market.

Small modular reactors represent the next generation of nuclear technology. They offer several advantages over traditional large-scale nuclear plants. SMRs can be manufactured off-site and assembled more quickly. They also feature enhanced safety systems and can be scaled to match energy demand more precisely.

The Ringhals location already hosts existing nuclear facilities, making it an ideal site for new development. The Värö Peninsula in Halland provides the necessary infrastructure and regulatory framework for nuclear operations. Local communities have experience with nuclear facilities, which may ease the approval process.

What does this mean for Sweden's energy future? The investment suggests major industrial players see nuclear power as essential for maintaining competitive electricity prices. These companies consume substantial energy in their manufacturing processes. They appear to be taking direct action to secure their long-term energy supply rather than relying solely on market mechanisms.

The fixed price agreement raises questions about cost distribution. While it provides certainty for investors, taxpayers may ultimately bear some risk if market prices diverge significantly from the agreed rate. The 40-year term represents an unusually long commitment in the energy sector.

This development reflects broader trends in Nordic energy policy. Several countries in the region are reconsidering nuclear power as they balance climate commitments with industrial competitiveness. The Swedish model of combining private investment with government guarantees could influence similar projects elsewhere.

The project faces several challenges ahead. Regulatory approvals, construction timelines, and public acceptance all represent potential hurdles. Still, the substantial financial commitment from established industrial companies suggests strong confidence in both the technology and the political support behind it.