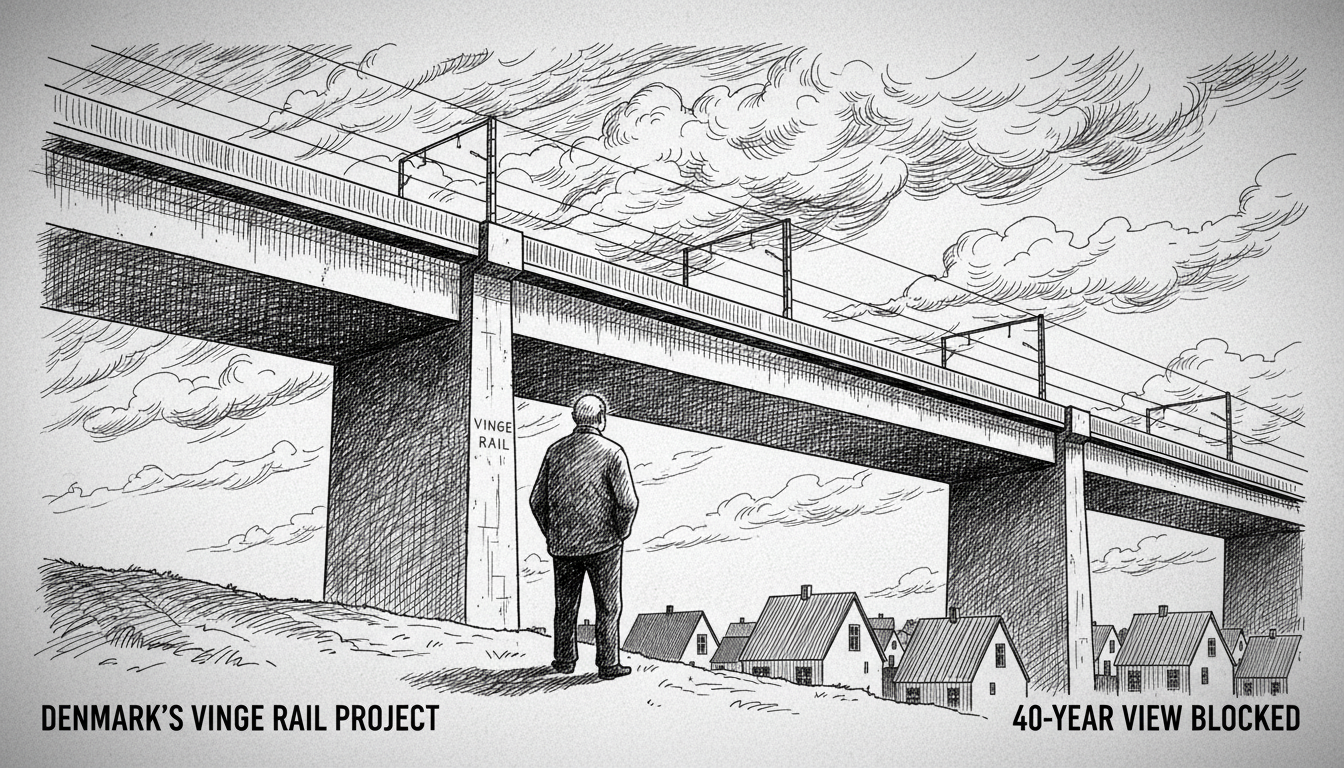

Denmark's ambitious Vinge development plan is creating a stark conflict between public infrastructure and private property rights, leaving one homeowner facing a colossal new neighbor with no financial recourse. For 40 years, Michael Kongstad has enjoyed a panoramic view of fields and forests from his home in Frederikssund. That view is set to be replaced by a 25,000-square-meter DSB workshop for driverless S-trains, a decision by the local council that he calls "a scandal."

"I thought it was a lie. And I thought, well then I shouldn't live here anymore," Kongstad said, reacting to the council's move to send the local plan for the workshop to public consultation. The project is a key piece of infrastructure for the new Vinge urban district, designed to be a sustainable residential hub connected to Copenhagen. But for Kongstad, it represents a profound personal and financial loss. "If it gets built, then our house will totally fall in value," he stated.

A Clash of Visions for Vinge

The Vinge development is one of Denmark's most significant urban expansion projects, envisioned as a modern, transit-oriented community. The DSB workshop is critical for maintaining the fleet of new driverless S-trains that will serve the area and greater Copenhagen. The facility, as outlined in the new local plan, would include the massive main hall, approximately 14 kilometers of track, and an additional 4,000 square meters for train washing and cleaning functions. DSB has stated it will install noise-dampening screens, but for nearby residents, these are small concessions against a massive change.

"It's just insane. It changes the whole area," Kongstad said, reviewing visualizations of the project prepared by engineering consultancy COWI for DSB. The renderings show his current vista of peaceful greenery replaced by industrial-scale architecture. The shift from a rural setting to an industrial-transport zone encapsulates the tension at the heart of modern Danish planning: balancing regional growth with the livability of existing communities.

The Cold Reality of Danish Compensation Law

Kongstad's frustration is compounded by a legal reality many homeowners find shocking. Under current Danish law, there is no automatic right to financial compensation for a loss of view, increased noise, or a potential drop in property value caused by a public infrastructure project like this, unless the property is subject to a compulsory purchase order. "The way I see it here and now, there is no possibility for any form of compensation. Unfortunately," Kongstad said, summarizing a common and painful dilemma.

Local real estate experts confirm his financial fears are well-founded. "I have no doubt that it will have an impact," said Allan Bendsen, a real estate agent and owner of Nybolig Frederikssund. He explained that selling a house with a view of a major railway workshop is far more difficult than selling one overlooking preserved woodland. The perceived nuisance of potential noise, light pollution, and visual intrusion directly translates to market value, a loss homeowners must bear alone.

The Broader Debate: Progress vs. Preservation

This case in Vinge is not isolated. It highlights a recurring debate in Danish urban planning and infrastructure development. As municipalities work to meet climate goals and population growth by densifying housing and improving public transport, existing residential areas on the urban fringe often pay the price. Experts note that while the societal benefit of a efficient train network is clear and widespread, the negative impacts are intensely localized and borne by a few.

"The legal framework is built on a principle of general societal benefit outweighing individual cost," said a Copenhagen-based urban planner who wished to remain anonymous due to ongoing work with municipalities. "The system expects homeowners to absorb a certain degree of change from neighboring development. The line for compensation is drawn very high, typically at direct physical encroachment or severe pollution. A ruined view or a speculative drop in value rarely crosses it."

This creates a political and ethical challenge. Projects like the Vinge workshop are voted on by municipal councils representing a broad electorate, while the consequences are felt by a small number of constituents. Frederikssund Council's majority decision to advance the plan demonstrates the political weight given to regional transportation infrastructure and long-term development goals.

A Look Ahead: Consultation and Construction

The local plan is now in a public consultation phase, where residents and stakeholders can formally submit objections or comments. However, given the project's scale and its alignment with broader regional transport strategy, significant alterations to its placement are considered unlikely. The consultation process often focuses on mitigating measures rather than fundamental changes.

For Michael Kongstad, the coming months mean living with uncertainty. The pastoral landscape that has defined his daily life for four decades is on borrowed time. His options are stark: adapt to a new reality dominated by a 15-meter-high industrial hall, or attempt to sell a property whose market appeal is fundamentally altered. His experience serves as a cautionary tale for homeowners living near the planned expansion zones of Denmark's major cities.

The Vinge workshop dispute underscores a critical question for Denmark's future development: as the country builds the sustainable infrastructure of tomorrow, how does it fairly address the individuals whose today is permanently disrupted? For now, the answer for people like Kongstad appears to be that they are expected to bear the cost for the public good, a trade-off that feels profoundly unjust from a living room staring at a vanishing forest.