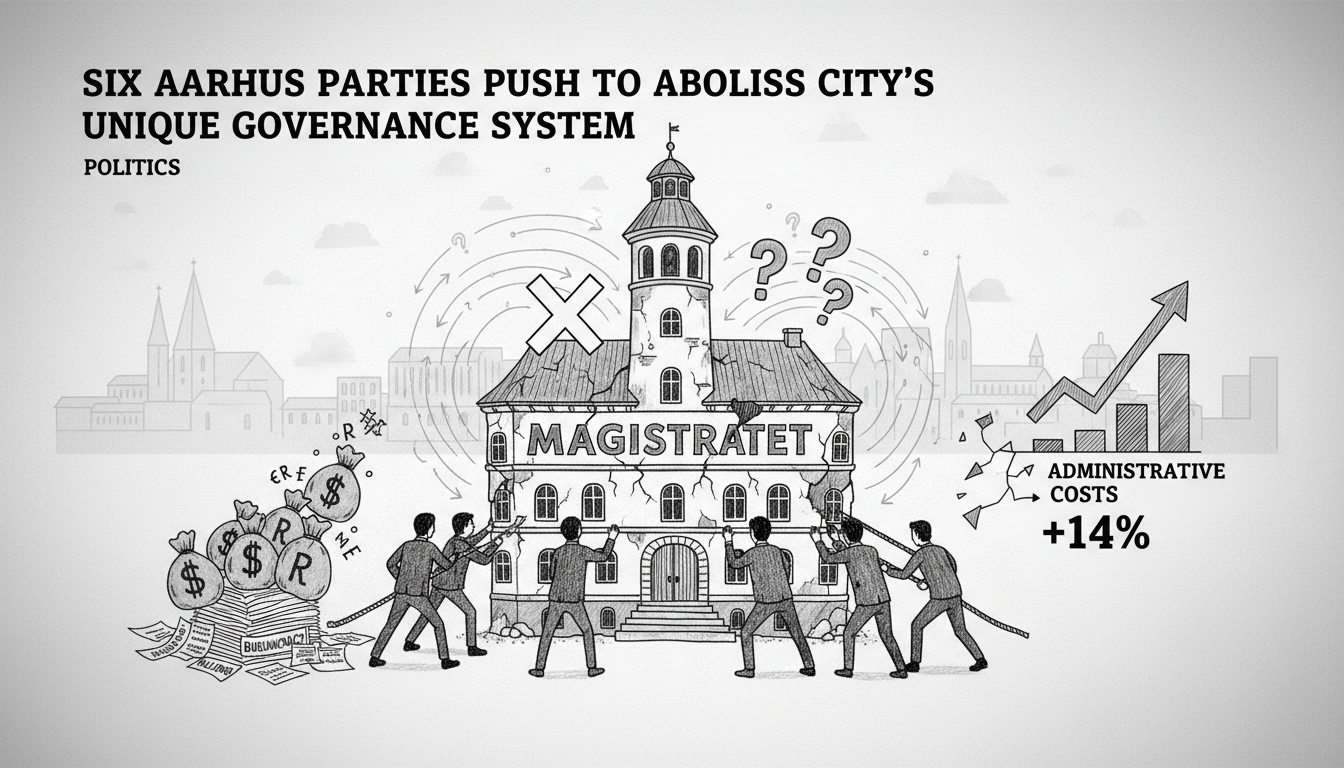

Six political parties in Aarhus want to eliminate the city's unique governance model. They claim the system creates unnecessary bureaucracy and costs taxpayers millions. The coalition spans both left and right-wing parties, showing rare political unity on this issue.

Aarhus remains the only municipality in Denmark using the magistrate governance system. This structure features multiple political leaders called councilors who each oversee different administrative departments. These councilors earn approximately 1.1 million Danish kroner annually, slightly less than the mayor's 1.4 million kroner salary.

Jakob Søgaard Clausen from the Denmark Democrats explained the problem. Many Aarhus residents experience frustration when dealing with city services. They often fall between different administrative chairs. The magistrate system creates confusion about responsibility when problems arise. Aarhus spends 14 percent more on administration compared to other Danish municipalities.

The current councilor positions are distributed among five parties: Socialist People's Party, Social Liberals, Conservatives, Liberals, and Social Democrats. These parties appear reluctant to surrender their administrative fiefdoms.

How does the magistrate system actually work? The city council functions like a national parliament, making final decisions on municipal matters. The magistrate serves as the executive government, preparing proposals for the council and implementing decisions. It consists of the mayor, five councilors, and three magistrate members.

This governance debate isn't new. Former Social Democratic Mayor Jacob Bundsgaard repeatedly tried to abolish the system. He argued it would save the municipality millions of kroner. His attempts failed due to lack of political support in the city council.

Current Social Democratic Mayor Anders Winnerskjold finds the proposal interesting but questions its viability. He isn't married to the current system but notes change requires broad political consensus. He doesn't see that consensus existing currently.

Other major Danish cities abandoned similar systems years ago. Copenhagen, Aalborg, and Odense all eliminated magistrate governance in 1998. They adopted intermediate governance models where standing committees manage municipal administration.

The six-party coalition hopes to send a clear message to the next mayor. They want whoever leads the city to champion governance reform. The unusual political alignment suggests growing frustration with the status quo.

What would replace the current system? The proposal likely involves moving toward the intermediate model used by other major cities. This could streamline decision-making and reduce administrative costs. It would also clarify responsibility when citizens encounter problems with municipal services.

The debate highlights broader questions about municipal efficiency. As Denmark's second-largest city, Aarhus faces complex administrative challenges. The current system may have suited past needs but appears increasingly outdated.

International readers might compare this to city manager systems in other countries. The Danish municipal structure differs significantly from systems in Anglo-American countries. Understanding these differences helps explain why governance reform generates such debate.

The financial implications cannot be overlooked. With five highly paid councilor positions at stake, the debate involves substantial budget considerations. In an era of tight municipal finances, these costs draw increased scrutiny.

The coming months will show whether this unusual coalition can build sufficient support. They need to convince other parties that change benefits both citizens and municipal finances. The outcome could reshape how Denmark's second city governs itself for decades.